Long before Joe Hill made horror a family tradition, Richard Christian Matheson was born of legendary Richard Matheson and began cranking out short-short genre fiction that appeared in The Twilight Zone and Night Cry magazines and 1980s anthologies edited by Charles L. Grant, Dennis Etchison, and Stuart David Schiff. While his name alone could have gotten him published, Matheson garnered much attention in the field on his own skill for stripping his stories to the absolute bone, with some consisting solely of one-word sentences or very nearly that. During an era in which horror showed a tendency to bloat and stuffing, some editors and readers found Matheson's pared-down work refreshing, while still maintaining edge and bite. For a short while he was aligned with the splatterpunks, mostly because he

was young and had a background in television (you know--so modern) and palled around with Skipp, Spector, Schow, et. al. My first experience with him was in 1986's Cutting Edge, which included "Vampire." It's just two pages of:

In the '80s I found it quite striking, and the title is more metaphor than literal. Today, I dunno, it seems more gimmicky than powerful. Which is the problem with Matheson's whole style of clipped brevity: does it engender more chills for the reader, is it essential to the story to be told so? What's frustrating about this wildly uneven collection (first published by Scream/Press in 1987, Tor Books paperback July 1988) is that the style is in service to stories that are threadbare and obvious, rife with twists and fillips that depend only on leaving out crucial details. Oh, the servant is a human and the served is a robot! Oh, they're not people, they're endangered whales! Oh, the little girl is death itself! If he'd just told us that stuff at the beginning then maybe there'd be an interesting story. Stories often end just when they should be beginning. They seem like tales told inside-out, writerly warm-up exercises to get to the good stuff. Except that never really happens, not like I remembered from first reading Scars in the early '90s.

Too many scenarios are redolent of moldy "Twilight Zone" and "Night Gallery" tropes: beware

"Sentences," "Obsolete," "Intruder," "Beholder," "Incorporation." Did Rod Serling come over and babysit a young Matheson?! Treacly beyond endurance, "Holiday"

rolls out a real Santa Claus, while the 60-page teleplay for an episode

of the Steven Spielberg-produced '80s TV anthology "Amazing Stories" is

well-nigh unreadable. Ballplaying kids and their grampas and dopey dogs

in a Norman Rockell town... oh god, spare me. Please. Try to read "Cancelled" without cringing at the ridiculous slangy

stream-of-consciousness and labored satire of crass network television shows. "Conversation Piece" was done with more subtle chills, sincerity, and thoughtfulness by Michael Blumlein with his "Bestseller." Graphic unsettling violence rears an ugly head--or ugly bump--in "Goosebumps," a bit of meta-horror that would be silly were it not for the image of a guy stabbing a butcher knife into his own mouth. It's still silly but now it makes you wince, so...

Is it ironic that "Graduation,"

which I'd read in Whispers, is probably Matheson's best work, and it was his first published? Written with strength and style and its

only gimmick is the letter-writer's references to "you-know-who" and

even on this second read I have no idea who that's supposed to be.

Unreliable narrators can be great devices for horror but not when the

reader has no way to grasp the truth. Still, I found it vivid and unsettling; "Graduation" has a precision that briefer works lack. Other standout works--the aforementioned "Vampire," "Mr. Right," "Red," "Dead End"--can be found in various anthologies. Editors chose wisely (Paul Sammon included the broiling, LA's burning, high-pressure radio-DJ nightmare "Hell" in Splatterpunks). I believe it was "Red" that got Matheson attention in the first place, and how could it not? It's about SPOILER a guy picking up parts of his daughter's mangled corpse off the road after he accidentally dragged her behind his car. Of course Matheson doesn't spell that out like I just did and while it's pretty shocking it kind of stretches the boundaries of belief. Would the police and EMTs even allow that?!

When you look at Matheson's TV-ography as a writer, it's prolific but the quality is actually rather dismal.

Highlights include such well-loved but not terribly brilliant shows like

"Three's Company," "Knight Rider," "The A-Team," and "The Incredible

Hulk," as well as not so-well-loved and not terribly brilliant shows

like "B.J. and the Bear" and "The Powers of Matthew Star." With that in

mind, the horror stories make more sense: they're not changing the

world, they're just entertaining you for 22 or 45 minutes or so. But they're entertaining you not because they've got a new vision; they're entertaining you because it's the familiar dressed up in unfamiliar garb. The only raison d'être is that twist, that surprise, so anything that would get in the way of that--character, dialogue, realism--is jettisoned. As I said, perhaps in the 1980s a writer could have gotten away with this--and obviously, he did!--but today, as a much more experienced reader and fan, I find Matheson's approach to horror fiction incredibly jejune.

I began to think of this collection as high-concept

horror: ideas that seem intriguing at first but are little more than

tiny gimmicks, not actual stories about real people and situations. His

penchant for writing stories made up of one-word sentences is

interesting at first, but when it's over you think, That's all? Despite

the introductory encomiums from Stephen King and Dennis Etchison, I was

very little impressed with Scars, and despite the Matheson family name, found it not very distinguishing at all.

Showing posts with label scream/press. Show all posts

Showing posts with label scream/press. Show all posts

Wednesday, April 1, 2015

Wednesday, July 2, 2014

In a Dark Country, Red Dreams Stay with You: The Horrors of Dennis Etchison

With his bleak, pessimistic, often quite violent tales of people drifting through a modern world of lost highways and all-night convenience stores, mistaken identities and secret sociopaths, how could Etchison have ended up anywhere but the horror shelves? His enigmatic yet striking stories gained plaudits from Stephen King, Ramsey Campbell, Charles L. Grant, and Karl Edward Wagner, and were published in two paperback collections by Berkley Books, 1984’s The Dark Country and 1987’s Red Dreams (both originally put out by specialty horror publisher Scream/Press several years prior, both with inimitable J.K. Potter covers).

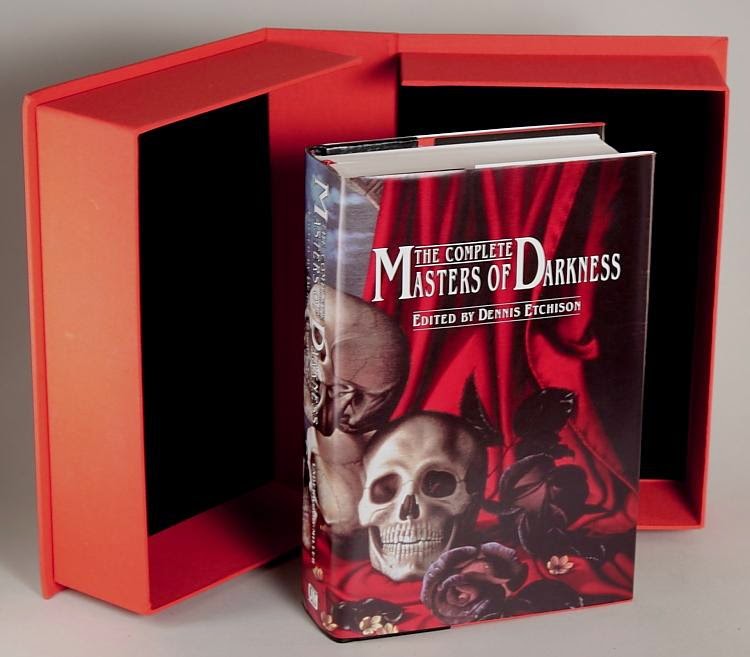

By the end of the 1980s Etchison had become a highly regarded editor as well, gathering brilliant and blisteringly horrific tales of all styles and voices from his most talented peers for the anthologies Cutting Edge (1986), Masters of Darkness (3 vols., 1986–1991), and MetaHorror (1992). If all that weren’t enough, under his pseudonym Jack Martin (a character with that name appears in many of his tales) he wrote novelizations for films by both John Carpenter and David Cronenberg! Let’s face it: Etchison may not have grown up wanting to be a horror writer per se, but he certainly knows his way around the oft-maligned genre. In his introduction to Cutting Edge, he gives a shorthand lesson in the failures of genre fiction during the modern era: Tolkien, Heinlein, and Lovecraft impersonators who refused to engage with the fracturing contemporary world around them. None of that for Etchison.

Etchison often sets his fictions in the desert highways and late-night byways of his home state; he knows well this empty land and the darknesses therein. Etchison is very good at writing scenes of shocking violence, but his fiction doesn’t rely on them, as so many horror writers do. There is much psychological violence, distress, dismay, a sense of things being not quite right, of a person not quite at home, wandering lost along a dark highway—and then meeting someone, or something, at the end of the night...

Of his two major collections, I am most partial to The Dark Country. While Red Dreams has its dark gems, the stories in the earlier collection seem darker, meaner, both more graphic and more effectively subtle. “The Late Shift,” one of his most lauded and original works which was first published in Kirby McCauley’s seminal anthology Dark Forces (1980), reveals a sinister source for those poor souls working the graveyard shift in 7-11s and gas stations and diners. Poor souls indeed.

The icy merciless horrors of “Calling All Monsters,” “The Dead Line,” and “The Machine Demands a Sacrifice,” which form what Ramsey Campbell calls in his introduction “the transplant trilogy... one of the most chilling achievements in contemporary horror.” Blurring SF and horror in a vaguely Ellisonian manner, Etchison offhandedly imagines a future (?) of living bodies at the service of some (mad) science, evoking specifically Dr. Moreau’s House of Pain. The sentence “This morning I put ground glass in my wife’s eyes,” begins “The Dead Line,” its no-nonsense, amoral tone invoking the hardboiled writers of the 1930s. More please!

“It Only Comes out at Night,” like its generic title, is a traditional horror piece, as is “Today’s Special,” but each is tightly written, offering horror fans the poisonous confections they love. The frigid vengeance of “We Have All Been Here Before” and especially “The Pitch” is quite satisfyingly nasty. Along with his talent for straightforward storytelling, Etchison has a skill for diversion, letting the reader think a story going’s one way when—record scratch—it goes somewhere else entirely. To wit: “Daughter of the Golden West,” which begins as a Bradbury-esque fantasy of three college-age men (the collection is dedicated to Bradbury) and ends with a revelation of one of California’s greatest tragedies. It’s a gruesome delight.

The title story won the 1982 British Fantasy Award and the World Fantasy Award for best short fiction. Nothing SF or noir or supernatural about this piece at all; it reads more like an autobiographical piece of an inadvertently nightmarish vacation. Jack Martin’s friends callously and drunkenly exploit locals at a Mexican beach resort, then he’s forced to face a fate dealt at random. This is not the kind of story you expect to find in a book with the little “horror” label on its spine, but does that even matter? It’s spectacular, mature and disturbing about everyday matters that can spiral out of control.

While The Dark Country is where the gruesome edge of Etchison’s blade resides, Red Dreams is its quieter sibling, but no less unsettling or insightful for that. The late great Karl Edward Wagner, in his intro, opines that Etchison’s nightmarish fiction is one made of loneliness, “of an individual adrift in a society beyond his control, beyond his comprehension, in which only sheeplike acceptance and robotlike nonawareness permit survival.” Ya got that right, K-Dub!

These are stories for grown-ups, their fears of age and insignificance—like the protagonist of “The Chair,” who attends his 20-year high school reunion and is called again and again by the wrong name, every time different, till one person gets it all too right. The father in “Wet Season” has faced a parent’s worst nightmare but then... it gets worse. “Drop City,” while overlong, is a noir/horror mash-up, slowly—perhaps too slowly—building to an impressionistic finale. A man wanders into a bar and discovers his life might not be anything he can remember. If the readers pays close attention, the ending will seem eerily familiar. "The Smell of Death" has a physician-heal-thyself angle inside its early '70s disaster SF setting; male/female relationships are in Etchison's spotlight (a common practice in his work) in "On the Pike," which has a young couple checking out the freakshow tent at a dilapidated carnival, one of them egging the performers on and on...

The thematically ambitious “Not from Around Here” finds Etchison in a quiet Phildickian mode as he slowly introduces us to a near-future and a religious cult whose texts provide perfect insight and pleasure. A lifelong movie fan, Etchison’s future world includes movies never made save in a film geek’s fevered imagination, works like, “Carpenter’s El Diablo, De Palma’s The Grassy Knoll, Cronenberg’s Cities of the Red Night, Spielberg’s Talking in the Dark...” (That’s rich, Etchison having Spielberg make a movie called “Talking in the Dark,” since that’s one of Etchison’s best horror stories!). I found it rather too leisurely in the telling, taking a long detour before getting to the real meat of the tale, but I dug the litany of classic movie actresses names that operate as a sort of exorcism for the protagonist, an acceptance as the promises of the cult are kept.

That "Talking in the Dark," the opening story, is probably the most horror-genre typical story in Red Dreams. A fan gets to meet his favorite horror writer! You know how writers hate being asked the utterly banal question “Where do you get your ideas?” (“Poughkeepsie” is Harlan Ellison’s eternal answer)? Here Etchison answers it. Sure, the inspiration’s real life; writers are regular people too. Except when they’re not. The blackly comic and bloodily conclusive scene sinks its teeth in.

Another favorite is “White Moon Rising,” a murder-on-coed-campus (shades of King’s “Strawberry Spring”) that fragments character POV as it climaxes. It originally appeared in Whispers, and was a standout of realistic horror amidst the dark fantasy included in that landmark anthology. But more than a handful of the stories in this collection are like stylized little writer's exercises, with the use of second-person narration, vague hints at interpersonal trauma, and existential-y questions of life and facing death; this is why Red Dreams had less of an impact on me than Dark Country. Still, both books should be in the serious horror fan's collection.

(This post originally appeared in slightly altered form as part of "The Summer of Sleaze" on the Tor.com website)

Saturday, August 24, 2013

The Brains of Rats by Michael Blumlein (1990): Just Agony. Not Death.

"The oldest and strongest emotion of mankind is fear, and the oldest and strongest kind of fear is fear of the unknown," H.P. Lovecraft famously wrote in the introduction to his own Supernatural Horror in Literature (1927). To that, might I be so bold as to add that the emotion of fear is also one of the most subjective? While it's true that most humans are afraid of most of the same things - spiders, snakes, disfigurement, public speaking, etc., etc., - when presented with fictional/artistic accounts renderings of things which are meant to scare us, our reactions will often be vastly different, based on the tenor of our private imaginations. Horror fans still argue over, say, whether The Blair Witch Project or The Shining were scary; naive readers want to know "the scariest books to read" for Halloween; fans of Lovecraft games and films find his stories "corny"; lists are compiled of the scariest this, that, or the other in horror entertainment and arguments rage in the comments section.

I don't participate in that discussion anymore: I don't read horror (or watch horror) to be scared. It's purely aesthetics for me; I simply love horror's palette, its recurrent images and themes and motifs, or new twists on said images and themes and motifs. Darkness and doom and death and despair, I love that shit. But it doesn't have to affect me directly, I don't have to be made to feel like someone or something is standing behind me or outside the window, that there is immediate and unavoidable danger lurking out there. If you're like me, if you get what I'm saying... read on.

This brings me to The Brains of Rats. With its intrinsic intelligence, its peerless caliber of prose, and over all, the stinging whiff of antiseptic which masks the stink of deceit and decay, the collection by Michael Blumlein (a practicing physician) is one of the landmarks of '80s/'90s horror fiction, a challenging yet rewarding work that offers the grimmest of delights for the reader looking not for another gorefest or spook story but for tales that disturb, bewilder, perplex, amaze, that unseat everyday perceptions so that the familiar seems strange and horrific but also... fresh, ready for new appraisal even.

Blumlein's visions emerge whole and complete, his mind's eye surgically sharpened to shock us from our stupor, to provoke us to question, to answer perhaps as well. His calm, unemotional prose reveals a desire to be absolutely clear and precise about difficult, uncomfortable subjects and ideas that often resist resolution - yet beneath that calm surface rages an emotional tumult. Although you won't see it in demonic contortions or blood-spattered climaxes; you will instead feel a quiet subtle whispering that touches your subconscious but leaves your brain tingling and your butt clenching. I just wouldn't describe the stories in Brains of Rats as scary - but they are still unsettling in a very great way.

I first read this collection in early 1991, spending about $30 on the original Scream/Press hardcover (below). It blew me away. So for ages now, having sold off my copy more than 10 years ago, I've wanted a revisit. While vacationing throughout Colorado, I found this Dell 1997 paperback reprint. These are stories Blumlein wrote throughout the 1980s, under the radar, for publications like Twilight Zone, Omni, Fantasy & Science Fiction, as well as more experimental, even postmodern mags like Interzone and Semiotext(e). Once you've read these stories you'll see why. If you're into J.G. Ballard, David Cronenberg, classic cyberpunk, that kinda thing, you'll appreciate Blumlein's icy new world.

I even reread a couple during my vacation, lounging around when not sightseeing, but eventually gave it up: the stories probed deep into pain, terror, confusion, grief, in a very immediate, intimate manner. There was no comfort, no ease, no escape - obviously not vacay reading. To begin, let's take the utterly stunning "Tissue Ablation and Variant Regeneration: A Case Report" for example: written in 1984, it concerns a then-current real world political figure and... well, some spoilers ahead.

Were it not so detached "Tissue Ablation" would be the blackest of satiric comedy; imagine Burroughs's Dr. Benway becoming one of America's most lauded surgeons. The story however is written in the exact style as it sounds: academic medical (you might get your Gray's Anatomy handy). This distances the reader only a tad; soon one realizes the enormity of the procedure being performed and - it can't be. Not that. It is nearly unimaginable, but with the good doctor detailing every slice, every incision, every removal in the most exacting words, we can see all too well the madness before us.

Oh man. In retrospect. Oh holy shit. This is where science fiction meets horror, and the punchline, as it were, is devastating. We're never given a reason as to why the world now works as we see here; the conviction of the piece, and its resolution, are the sole reason why. Politically "Tissue Ablation" is a raging, maddened polemic; artistically it shares roots with Swift's "A Modest Proposal." As a work of horror, it is truly "horrible" yet not without its own kind of cold efficient beauty. It's one of the strangest - and best - stories of '80s horror.

Much of Brains of Rats concerns gender differences both at the biological and the social strata, a theme which appears in nearly every story. These are ideas virtually never addressed in horror fiction of this era. Are we defined by our brains? Our genitalia? Some intermingling of each? Is what we think of as "natural" simply what our bodies are? Is mind not nature? The title story begins with the detached authority of a science textbook, even when it becomes about more than simple - or not so simple - scientific facts. The cadence is almost hypnotizing, and finally ominous:

Blumlein lulls you with his matter-of-fact languor, but when the physician narrator turns on a dime to state his ability, you're left almost breathless. Characters represent at times perhaps not individual people but states of mind, philosophies, idealized members of the opposite sex. As he continues, offering snippets of evolutionary biology, autobiography, history, and philosophy, the amorality shocks but the conceit intrigues. More, we say, even as we recoil. More.

I felt almost in familiar territory with "Keeping House," a tale that wouldn't have seemed too unusual from Ramsey Campbell's pen. In first-person narration, a woman details how she and her husband purchase a house, one of a pair of identical structures built next to each other. The couple disagrees which to buy. Would it have mattered? Something seems wrong from the start; she blames the house next door. Her efforts to exorcize this "entity" through will power - I found a way in my mind to merge one wall of the house with another, eliminating perspective and the lessons of vision. Solid forms I deconstructed, melting their complex geometries into simpler dimensions - then reminded me of Ballard's Atrocity Exhibition. Then, our narrator notices filth and noxious odors everywhere, can't stop cleaning, disinfecting, comes to think her very own family, husband and infant daughter, are responsible; even her own sexuality is suspect. The final lines seem almost foreordained even as her behavior seems almost incomprehensible. Marvelous and accomplished stuff, definitely a high point of the collection.

Others: "The Wet Suit," with its quiet, uneventful denouement, could almost be a piece of realistic New Yorker-style fiction, except the wet suit of the title belongs to the deceased father of a middle-class family whose son learns of its vast fetishistic importance in the man's life. An importance, the son learns, everyone else in the family already knew... More Ballardian insanity in "Shed His Grace," all video mediation and clinical political pornography. Some classic cyberpunk stylings feature in "Drown Yourself" and "The Glitter and the Glamour." The former is (almost) straight out of Gibson's Burning Chrome, in which two androids "meet cute" in a wailing nightclub, while the latter reads like sentences were edited out, perhaps, to leave only an impressionistic jangle in the mind as we subconsciously put the story - future clone of some schmaltzy lounge singer? - back together again.

And most unexpectedly, Blumlein can break your heart: in "The Thing Itself," friends and lovers grapple with sickness and love and death. Myth, poetry, imagination: the real and the unreal at once, all intertwine to make peace with finality. The climax, perhaps a eulogy, perhaps a dream, perhaps only a journal entry or unmailed letter, is nearly the most touching I've ever read in horror fiction.

And finally, "Bestseller," one of the bitterest, saddest tales about the economics of earning a living by the written word as any by Karl Edward Wagner or David J. Schow or Lovecraft, even.

It is also the most startling, making literal a metaphor about one "breathing life" into one's art. Simply spectacular.

And the intro: oh, look, it's by our old pal Michael McDowell, the late lamented author of seminal '80s horror works like Cold Moon over Babylon, The Amulet, and The Blackwater series. It is a perceptive and faintly envious piece: I urge you to read it before the stories - you'll find no spoilers. McDowell states that "Blumlein's is a dignity of narration delineating madness and aberration. Even the stories that are 'predictable' such as the Who's-the-Android narrative of 'Drown Yourself' become treatises on passion and obsession." Indeed.

I will state it plain: The Brains of Rats is excellent, a rarity in '80s horror fiction, an adult work of brave and bristling smarts, skill, and fearlessness, as true and honest and uncompromising as the genre gets (which it so often isn't very). These stories are not for those who think horror is only skeletons and slime and gore and ghosts, who long to identify with everyday-folks protagonists, who want tidy oh-so-that's-what-it-all-meant finales, who want to step vicariously into the driver's mind-seat of the insane. So the stories aren't "scary" - Michael Blumlein has given us something better, unparalleled in power: a freezing, eye-watering blast of fear and pain from the most desolate and despairing of mysterious countries, that one of meat cradled within our skulls.

I don't participate in that discussion anymore: I don't read horror (or watch horror) to be scared. It's purely aesthetics for me; I simply love horror's palette, its recurrent images and themes and motifs, or new twists on said images and themes and motifs. Darkness and doom and death and despair, I love that shit. But it doesn't have to affect me directly, I don't have to be made to feel like someone or something is standing behind me or outside the window, that there is immediate and unavoidable danger lurking out there. If you're like me, if you get what I'm saying... read on.

This brings me to The Brains of Rats. With its intrinsic intelligence, its peerless caliber of prose, and over all, the stinging whiff of antiseptic which masks the stink of deceit and decay, the collection by Michael Blumlein (a practicing physician) is one of the landmarks of '80s/'90s horror fiction, a challenging yet rewarding work that offers the grimmest of delights for the reader looking not for another gorefest or spook story but for tales that disturb, bewilder, perplex, amaze, that unseat everyday perceptions so that the familiar seems strange and horrific but also... fresh, ready for new appraisal even.

Blumlein's visions emerge whole and complete, his mind's eye surgically sharpened to shock us from our stupor, to provoke us to question, to answer perhaps as well. His calm, unemotional prose reveals a desire to be absolutely clear and precise about difficult, uncomfortable subjects and ideas that often resist resolution - yet beneath that calm surface rages an emotional tumult. Although you won't see it in demonic contortions or blood-spattered climaxes; you will instead feel a quiet subtle whispering that touches your subconscious but leaves your brain tingling and your butt clenching. I just wouldn't describe the stories in Brains of Rats as scary - but they are still unsettling in a very great way.

I first read this collection in early 1991, spending about $30 on the original Scream/Press hardcover (below). It blew me away. So for ages now, having sold off my copy more than 10 years ago, I've wanted a revisit. While vacationing throughout Colorado, I found this Dell 1997 paperback reprint. These are stories Blumlein wrote throughout the 1980s, under the radar, for publications like Twilight Zone, Omni, Fantasy & Science Fiction, as well as more experimental, even postmodern mags like Interzone and Semiotext(e). Once you've read these stories you'll see why. If you're into J.G. Ballard, David Cronenberg, classic cyberpunk, that kinda thing, you'll appreciate Blumlein's icy new world.

I even reread a couple during my vacation, lounging around when not sightseeing, but eventually gave it up: the stories probed deep into pain, terror, confusion, grief, in a very immediate, intimate manner. There was no comfort, no ease, no escape - obviously not vacay reading. To begin, let's take the utterly stunning "Tissue Ablation and Variant Regeneration: A Case Report" for example: written in 1984, it concerns a then-current real world political figure and... well, some spoilers ahead.

Were it not so detached "Tissue Ablation" would be the blackest of satiric comedy; imagine Burroughs's Dr. Benway becoming one of America's most lauded surgeons. The story however is written in the exact style as it sounds: academic medical (you might get your Gray's Anatomy handy). This distances the reader only a tad; soon one realizes the enormity of the procedure being performed and - it can't be. Not that. It is nearly unimaginable, but with the good doctor detailing every slice, every incision, every removal in the most exacting words, we can see all too well the madness before us.

I would be lying if I claimed that [the patient] was not in constant and excruciating pain... In retrospect, I should've carried out a high transection of the spinal cord, thus interrupting most of the nerve fibers to his brain, but I did not think of it beforehand and during the operation was too occupied with other concerns.

Oh man. In retrospect. Oh holy shit. This is where science fiction meets horror, and the punchline, as it were, is devastating. We're never given a reason as to why the world now works as we see here; the conviction of the piece, and its resolution, are the sole reason why. Politically "Tissue Ablation" is a raging, maddened polemic; artistically it shares roots with Swift's "A Modest Proposal." As a work of horror, it is truly "horrible" yet not without its own kind of cold efficient beauty. It's one of the strangest - and best - stories of '80s horror.

Much of Brains of Rats concerns gender differences both at the biological and the social strata, a theme which appears in nearly every story. These are ideas virtually never addressed in horror fiction of this era. Are we defined by our brains? Our genitalia? Some intermingling of each? Is what we think of as "natural" simply what our bodies are? Is mind not nature? The title story begins with the detached authority of a science textbook, even when it becomes about more than simple - or not so simple - scientific facts. The cadence is almost hypnotizing, and finally ominous:

The struggle between sexes, the battles for power are a reflection of the schism between thought and function, between the power of our minds and powerlessness in the face of our design. Sexual equality, an idea present for hundreds of years, is subverted by instincts present for millions. The genes determining mental capacity have evolved rapidly; those determining sex have been stable for eons. Humankind suffers the consequences of this disparity, the ambiguities of identity, the violence between the sexes. This can be changed. It can be ended. I have the means to do it.

Blumlein lulls you with his matter-of-fact languor, but when the physician narrator turns on a dime to state his ability, you're left almost breathless. Characters represent at times perhaps not individual people but states of mind, philosophies, idealized members of the opposite sex. As he continues, offering snippets of evolutionary biology, autobiography, history, and philosophy, the amorality shocks but the conceit intrigues. More, we say, even as we recoil. More.

I felt almost in familiar territory with "Keeping House," a tale that wouldn't have seemed too unusual from Ramsey Campbell's pen. In first-person narration, a woman details how she and her husband purchase a house, one of a pair of identical structures built next to each other. The couple disagrees which to buy. Would it have mattered? Something seems wrong from the start; she blames the house next door. Her efforts to exorcize this "entity" through will power - I found a way in my mind to merge one wall of the house with another, eliminating perspective and the lessons of vision. Solid forms I deconstructed, melting their complex geometries into simpler dimensions - then reminded me of Ballard's Atrocity Exhibition. Then, our narrator notices filth and noxious odors everywhere, can't stop cleaning, disinfecting, comes to think her very own family, husband and infant daughter, are responsible; even her own sexuality is suspect. The final lines seem almost foreordained even as her behavior seems almost incomprehensible. Marvelous and accomplished stuff, definitely a high point of the collection.

Blumlein's first novel, 1987

Others: "The Wet Suit," with its quiet, uneventful denouement, could almost be a piece of realistic New Yorker-style fiction, except the wet suit of the title belongs to the deceased father of a middle-class family whose son learns of its vast fetishistic importance in the man's life. An importance, the son learns, everyone else in the family already knew... More Ballardian insanity in "Shed His Grace," all video mediation and clinical political pornography. Some classic cyberpunk stylings feature in "Drown Yourself" and "The Glitter and the Glamour." The former is (almost) straight out of Gibson's Burning Chrome, in which two androids "meet cute" in a wailing nightclub, while the latter reads like sentences were edited out, perhaps, to leave only an impressionistic jangle in the mind as we subconsciously put the story - future clone of some schmaltzy lounge singer? - back together again.

And most unexpectedly, Blumlein can break your heart: in "The Thing Itself," friends and lovers grapple with sickness and love and death. Myth, poetry, imagination: the real and the unreal at once, all intertwine to make peace with finality. The climax, perhaps a eulogy, perhaps a dream, perhaps only a journal entry or unmailed letter, is nearly the most touching I've ever read in horror fiction.

I remember the last morphine shot, the one that let you lie back, that let the knotted muscles in your chest and neck finally ease. The room was dark, your friends circled the bed like a hand. One by one they told the stories, they made a web of memories with you at the center.

Not the usual "unputdownable" or King-style encomiums

And finally, "Bestseller," one of the bitterest, saddest tales about the economics of earning a living by the written word as any by Karl Edward Wagner or David J. Schow or Lovecraft, even.

The monkey sits on our head, we sit on the monkey. I finish the book, and an hour later the doctor calls to say that my young son has cancer. Cancer. What is the heart to do? Between exhilaration at completing the book and this sudden grief, my heart chooses the later. It is my son. They want to cut off his leg.

It is also the most startling, making literal a metaphor about one "breathing life" into one's art. Simply spectacular.

And the intro: oh, look, it's by our old pal Michael McDowell, the late lamented author of seminal '80s horror works like Cold Moon over Babylon, The Amulet, and The Blackwater series. It is a perceptive and faintly envious piece: I urge you to read it before the stories - you'll find no spoilers. McDowell states that "Blumlein's is a dignity of narration delineating madness and aberration. Even the stories that are 'predictable' such as the Who's-the-Android narrative of 'Drown Yourself' become treatises on passion and obsession." Indeed.

I will state it plain: The Brains of Rats is excellent, a rarity in '80s horror fiction, an adult work of brave and bristling smarts, skill, and fearlessness, as true and honest and uncompromising as the genre gets (which it so often isn't very). These stories are not for those who think horror is only skeletons and slime and gore and ghosts, who long to identify with everyday-folks protagonists, who want tidy oh-so-that's-what-it-all-meant finales, who want to step vicariously into the driver's mind-seat of the insane. So the stories aren't "scary" - Michael Blumlein has given us something better, unparalleled in power: a freezing, eye-watering blast of fear and pain from the most desolate and despairing of mysterious countries, that one of meat cradled within our skulls.

Friday, March 30, 2012

Dennis Etchison Born Today, 1943, and More!

Birthday greetings to horror editor and author extraordinaire Dennis Etchison. Above is the 1984 Scream/Press hardcover of Red Dreams; the paperback edition has been on my want-list for awhile now. Below are Shadowman (Dell/Abyss Feb '93) and California Gothic (Dell '95), which I have not read. But his The Dark Country made my best-of-2011 list, and Cutting Edge is a very good, very eclectic '80s horror anthology.

Birthday greetings to horror editor and author extraordinaire Dennis Etchison. Above is the 1984 Scream/Press hardcover of Red Dreams; the paperback edition has been on my want-list for awhile now. Below are Shadowman (Dell/Abyss Feb '93) and California Gothic (Dell '95), which I have not read. But his The Dark Country made my best-of-2011 list, and Cutting Edge is a very good, very eclectic '80s horror anthology.

On to other stuff: how about some horror fiction help? Couple emails I've received in the past month or two here:

On to other stuff: how about some horror fiction help? Couple emails I've received in the past month or two here:Nick writes of a book, about a family moving into this house and they had a son who seemed to be the protagonist that had to deal with the monster or ghost. Cover was a picture of a house and I believe the house was twisted and looked like some kind of demonic face...

John writes, A family moves to New England. Wouldn't you know it, the oldest son soon grows distant and more reclusive, eventually moving into the basement. The family is content to leave him down there, listening to his music and being a teenager. Eventually he paints the basement all black, blacks out the windows, etc. At the climax of the novel, a parent (the mother?) goes down there to find that he is just about to open a portal to hell, assisted by a few red-robed supernatural beings doing some kind of supernatural incantation over a supernatural altar. The parent is able to disrupt the ceremony, portal to hell closed, fin.

The book would have been published in paperback sometime between 1994-1996. As I recall, the cover was purple with the outline of a house in the foreground.

Also: yesterday I spent three hours at the Wake County Public Libraries Booksale - and oh my god, what vintage horror paperback treasures I found! I wasn't in the horror section but oh, five seconds before I'd found several of my most sought-after titles. Many were in mint condition, as if they been vacuum-sealed for decades. You fellow obsessive book-buyers will know the feeling of disbelief and excitement that accompanied my visit. Tables and tables of paperback horror amidst tables and tables and tables of books in an enormous warehouse. Gobsmacking. You'll have to wait, though, to find out what I bought - all for $2 each! Right now I'm in the middle of a Dell Abyss paperback as well as reading stories in another great anthology. Hope to have some reviews up by next week!

Tuesday, August 23, 2011

The Dark Country by Dennis Etchison (1982): Nightmares Stay with You

For some time I've been searching for a copy of Dennis Etchison's first collection of short fiction, entitled The Dark Country. Finally found it on my recent trip to my hometown! Originally published by specialty publisher Scream/Press, this paperback is from Berkley in 1984. It consists of Etchison's stories from the 1970s, and his World Fantasy Award-winning 1981 title tale. Like Stephen King, Etchison had many of his short works appear in men's magazines of the day, as well as various anthologies edited by Charles L. Grant and Kirby McCauley. Interestingly, for an author so associated with the horror genre, lots of his stories here could be classified as crime noir and science fiction rather than supernatural horror. Perhaps they all fall under the never-clear "dark fantasy" tag which Grant touted.

For some time I've been searching for a copy of Dennis Etchison's first collection of short fiction, entitled The Dark Country. Finally found it on my recent trip to my hometown! Originally published by specialty publisher Scream/Press, this paperback is from Berkley in 1984. It consists of Etchison's stories from the 1970s, and his World Fantasy Award-winning 1981 title tale. Like Stephen King, Etchison had many of his short works appear in men's magazines of the day, as well as various anthologies edited by Charles L. Grant and Kirby McCauley. Interestingly, for an author so associated with the horror genre, lots of his stories here could be classified as crime noir and science fiction rather than supernatural horror. Perhaps they all fall under the never-clear "dark fantasy" tag which Grant touted.But this is all academic: what's important is that Etchison's stories are crafted with a true writer's care and originality, although at times his penchant for experimentation and quiet intimation can lose even careful readers. Like me. Therefore I suppose you won't be surprised to learn that one Ramsey Campbell introduces The Dark Country...

A California son, Etchison often sets his fictions in the desert highways and late-night byways of his home state; he knows well this empty land and the darknesses therein. "The Late Shift," one of his more well-known works that was first published in the seminal Dark Forces (1980), reveals a sinister source for those poor souls working the graveyard shift in 7-11s and gas stations and diners throughout that region. I adored "Daughter of the Golden West," which begins as a Bradbury-esque fantasy of three college-age men (the collection is dedicated to Bradbury) and ends with a revelation of one of California's greatest tragedies. Reading the noir-ish "The Walking Man" put me in mind of the spectacular "modern" noir film Body Heat (1981) and once again shows how the horror and crime genres uneasily shadow one another.

A California son, Etchison often sets his fictions in the desert highways and late-night byways of his home state; he knows well this empty land and the darknesses therein. "The Late Shift," one of his more well-known works that was first published in the seminal Dark Forces (1980), reveals a sinister source for those poor souls working the graveyard shift in 7-11s and gas stations and diners throughout that region. I adored "Daughter of the Golden West," which begins as a Bradbury-esque fantasy of three college-age men (the collection is dedicated to Bradbury) and ends with a revelation of one of California's greatest tragedies. Reading the noir-ish "The Walking Man" put me in mind of the spectacular "modern" noir film Body Heat (1981) and once again shows how the horror and crime genres uneasily shadow one another.The maddeningly enigmatic "You Can Go Now" finishes without wrapping and bow but I found its dream-like, episodic psychological structure utterly intriguing. Chilling, sad, realistic stuff... even if perhaps it doesn't quite come together. "Calling All Monsters," "The Dead Line," and "The Machine Demands a Sacrific" form what Campbell calls the "transplant trilogy... one of the most chilling achievements in contemporary horror." Blurring SF and horror in a vaguely Ellisonian manner, Etchison offhandedly imagines a future (?) of living bodies at the service of some (mad) science, evoking Moreau's House of Pain. The breaking mind of a man in extremis:

O now the obscene sucking sound growing fainter even as my hearing dissolves, wet tissue pulling apart. They suction my blood, the incision clamped wide like another mouth a monstrous Caesarean and I hear the shiny scissors clipping tissues clipping fat, the automated scalpels striking tictactoe on my torso and i know they are taking me, the blood in my head tingles draining down down and I am almost gone, O what are they doing to me the monsters ME they must be it can't be that other... I have seen the altered specimen on the table the wrapped composite the sutured One Who Waits drifting in fluid for the new brain the shaved skin the transplanted claws the feral rictus the excised hump

Others: I didn't have much for "The Nighthawk," a gothic-y tale of siblings on the rainy California coast, nor "Deathtracks." Writing's good, stories not so much. The first story, "It Only Comes out at Night," despite its generic title, is a nice little traditional horror piece, as is "Today's Special." The frigid vengeance of "We Have All Been Here Before" and especially "The Pitch" is quite satisfyingly nasty. Etchison has a skill for diversion, letting you think a story going's one way when - record scratch - it goes somewhere else.

Now, on to the award-winning title story. Nothing SF or noir or supernatural about this piece at all; it reads more like an autobiographical piece (the protagonist's name is Jack Martin, Etchison's pseudonym) of an inadvertently nightmarish vacation. His friends callously and drunkenly exploit locals at a Mexican beach resort, then he's forced to face a fate dealt at random. This is not the kind of story you expect to find in a book with the little "HORROR" label on its spine. Does that matter? I still don't know. Somewhere Martin/Etchison wait, probably not knowing either, hoping... but fearing, as always, the worst.

Now, on to the award-winning title story. Nothing SF or noir or supernatural about this piece at all; it reads more like an autobiographical piece (the protagonist's name is Jack Martin, Etchison's pseudonym) of an inadvertently nightmarish vacation. His friends callously and drunkenly exploit locals at a Mexican beach resort, then he's forced to face a fate dealt at random. This is not the kind of story you expect to find in a book with the little "HORROR" label on its spine. Does that matter? I still don't know. Somewhere Martin/Etchison wait, probably not knowing either, hoping... but fearing, as always, the worst.

Monday, June 13, 2011

Skeleton Crew by Stephen King (1985): Many Dead at Many Scenes

"I got to thinking about cannibalism one day - because that's the sort of thing guys like me sometimes think about - and my muse once more evacuated its magic bowels on my head. I know how gross that sounds, but it's the best metaphor I know, inelegant or not..."

King on his 1982 story "Survivor Type"

King on his 1982 story "Survivor Type"

Does that sum up Stephen King or does that sum up Stephen King? I mean really. Gathering stories that he'd written from his earliest days as a writer until the mid-1980s, Skeleton Crew is King's second collection. You've probably read it, right? Right. If you're like me you pored over it, trying to figure out the inner mechanics of King's seemingly effortless storytelling and characters so real you could almost smell the Black Label on their breath. I was 15 or 16 when I read Skeleton Crew for the first time, which is about the perfect age for stories featuring such an assortment of giant primordial bugs and psychos masquerading as regular folks.

Without a doubt, the opening novella "The Mist" is one of King's best and simply one of my favorite stories in all the English language. It first appeared in the 1980 anthology Dark Forces; in Skeleton Crew it appears mildly rewritten, most noticeably in the final sentences, but that doesn't change much. I can lose myself in that story again and again and again; at this point I think it's fused with my DNA. "The Mist" is deliriously fantastic and fatalistic, ridiculous and sublime, all at once. Who can ever forget those two Cyclopean legs going up and up into the mist like living towers...? Not me, friends and neighbors, not me.

Without a doubt, the opening novella "The Mist" is one of King's best and simply one of my favorite stories in all the English language. It first appeared in the 1980 anthology Dark Forces; in Skeleton Crew it appears mildly rewritten, most noticeably in the final sentences, but that doesn't change much. I can lose myself in that story again and again and again; at this point I think it's fused with my DNA. "The Mist" is deliriously fantastic and fatalistic, ridiculous and sublime, all at once. Who can ever forget those two Cyclopean legs going up and up into the mist like living towers...? Not me, friends and neighbors, not me. "Mrs. Todd's Shortcut" is another favorite, an old-timer's tale of a uniquely desirable woman whose search for the quickest route around town leads her through a landscape not on any earthly map. Dig what the narrator says about "the Todd woman": "I like a woman who will laugh when you don't have to point her right at the joke, you know." While King is aware of the "wonky science" in "The Jaunt," it remains an icily unsettling SF tale of the "history" of teleportation, related by a father to his family as they prepare to "jaunt" to Mars. Enter one portal, get disintegrated, and come out the other, whether it's across the room or across the galaxy. The climax is one of King's most notorious; a fondly remembered shock of sheer madness.

"Mrs. Todd's Shortcut" is another favorite, an old-timer's tale of a uniquely desirable woman whose search for the quickest route around town leads her through a landscape not on any earthly map. Dig what the narrator says about "the Todd woman": "I like a woman who will laugh when you don't have to point her right at the joke, you know." While King is aware of the "wonky science" in "The Jaunt," it remains an icily unsettling SF tale of the "history" of teleportation, related by a father to his family as they prepare to "jaunt" to Mars. Enter one portal, get disintegrated, and come out the other, whether it's across the room or across the galaxy. The climax is one of King's most notorious; a fondly remembered shock of sheer madness.Other fondly remembered shocks for lots of fans are "The Raft" and the above-mentioned "Survivor Type," stories that are inimitably King but also hark back to the blackly-humored grotesqueries of EC horror comics, although "The Raft" also has a strangely elegiacal tone, especially in its strange and doomed refrain of "Do you love?" What else would you expect from a story about a ravenous bit of oily muck in an inviting lake? He referred to "Survivor Type" in Danse Macabre as an example of a story he didn't think he'd ever be able to publish, but it was, finally, in a Charles L. Grant anthology. A surgeon/drug smuggler/junkie ends up a castaway on a little spit of land with little hope of rescue. His supplies? His medical kit, some heroin, and a near-superhuman will to survive...

King's influences come hard and fast in Skeleton Crew: "Gramma" and of course "The Mist" have the merest whisper of Lovecraft. The echo of Shirley Jackson is loud and clear in "Here There Be Tygers," and Charles Beaumont gets a sort of retake in the jazz-based "The Wedding Gig," which reminded me of Beaumont's classic "Black Country." "Nona" is pure James M. Cain or Cornell Woolrich noir, complete with a drifter, his sordid and alienated past, and the mysterious femme fatale he meets on the road. Even Peter Straub's Chowder Society seems to appear in "The Man Who Would Not Shake Hands." And do you hear an echo of Harlan Ellison's jaunty modern fantasy in the title "The Ballad of the Flexible Bullet" too? Despite their familiarity, these stories are captivating and still purely King. When the young narrator of "Nona" beats the unholy shit out of a road-scarred trucker in a diner parking lot, you can practically taste the gravel and blood in your teeth.

King's influences come hard and fast in Skeleton Crew: "Gramma" and of course "The Mist" have the merest whisper of Lovecraft. The echo of Shirley Jackson is loud and clear in "Here There Be Tygers," and Charles Beaumont gets a sort of retake in the jazz-based "The Wedding Gig," which reminded me of Beaumont's classic "Black Country." "Nona" is pure James M. Cain or Cornell Woolrich noir, complete with a drifter, his sordid and alienated past, and the mysterious femme fatale he meets on the road. Even Peter Straub's Chowder Society seems to appear in "The Man Who Would Not Shake Hands." And do you hear an echo of Harlan Ellison's jaunty modern fantasy in the title "The Ballad of the Flexible Bullet" too? Despite their familiarity, these stories are captivating and still purely King. When the young narrator of "Nona" beats the unholy shit out of a road-scarred trucker in a diner parking lot, you can practically taste the gravel and blood in your teeth.The source for the cover art by Don Brautigam, a long-forgotten child's toy wreaks its horror in "The Monkey," terrifying an adult man who thought it forever gone. What would that toy say if it had a chance? Stephen King knows:

Thought you got rid of me, didn't you? But I'm not that easy to get rid of, Hal... We were made for each other, just a boy and his pet monkey, a couple of good old buddies... I came to you, Hal, I worked my way along the country roads at night and the moonlight shone off my teeth at three in the morning and I left many people Dead at many Scenes. I came to you, Hal, I'm your Christmas present, so wind me up, who's dead...?

"The Reach" is mainstream King, a heartfelt story of real places and real people and ghosts that haunt not houses but the human heart; it ends this collection on a high note. As for the poems "Paranoid: A Chant" and "For Owen," I really can't say much whatsoever. A handful of stories here date from the late 1960s, such as "Cain Rose Up" and "The Reaper's Image," milder works that still point toward his bestselling future.

Still I'm not blind to King's weaknesses as a writer: he can be corny and overly familiar in the middle of a tale of creeping dread, using dull down-home humor in asides that almost seem like self-mockery. His acknowledged tendency to overwriting, to bloat and stuffing, can deflate the delicate suspension of disbelief one needs for horror fiction and render a story inert. He can be shallow and perhaps glib, showing his pulp roots. And sometimes his characters talk too damn much, or he gets mired in their italicized thought processes. And perhaps I'm simply not quite as enamored of drunken Maine rednecks and their fatal shenanigans as I once was.

Still I'm not blind to King's weaknesses as a writer: he can be corny and overly familiar in the middle of a tale of creeping dread, using dull down-home humor in asides that almost seem like self-mockery. His acknowledged tendency to overwriting, to bloat and stuffing, can deflate the delicate suspension of disbelief one needs for horror fiction and render a story inert. He can be shallow and perhaps glib, showing his pulp roots. And sometimes his characters talk too damn much, or he gets mired in their italicized thought processes. And perhaps I'm simply not quite as enamored of drunken Maine rednecks and their fatal shenanigans as I once was. I can't finish up without mentioning that I really enjoy King's intro (PS: There really was more beer in the fridge, and I drank it myself after you were gone that day) and end notes. When I was a young aspiring fiction writer, I looked to King because he gave a sort of behind-the-scenes glimpse of the writing life in these pieces, which I often got more out of than his stories (much the same is true for me with the mighty Harlan Ellison). Personable and folksy, he lets you in on his writing process, how his brain spits up (or shits out) ideas, how he submits his stories and how many times they were rejected. He's well aware of his weaknesses and foibles but also knows he's got an unparalleled imagination that is often more powerful and demanding than he knows what to do with. Skeleton Crew might not - might not - reach the rarefied heights of Night Shift, but it's still an essential read for horror fiction fans. As if you could be one and not already have read it...

I can't finish up without mentioning that I really enjoy King's intro (PS: There really was more beer in the fridge, and I drank it myself after you were gone that day) and end notes. When I was a young aspiring fiction writer, I looked to King because he gave a sort of behind-the-scenes glimpse of the writing life in these pieces, which I often got more out of than his stories (much the same is true for me with the mighty Harlan Ellison). Personable and folksy, he lets you in on his writing process, how his brain spits up (or shits out) ideas, how he submits his stories and how many times they were rejected. He's well aware of his weaknesses and foibles but also knows he's got an unparalleled imagination that is often more powerful and demanding than he knows what to do with. Skeleton Crew might not - might not - reach the rarefied heights of Night Shift, but it's still an essential read for horror fiction fans. As if you could be one and not already have read it...Thursday, July 8, 2010

Toplin by Michael McDowell (1985): The World's Forgotten Boy

Toplin fits very few subcategories of horror fiction, and upon finishing I'm not entirely sure the word "Horror" on its spine is deserved; it's unsettling in places but not scary. But then I'm not sure what genre would be appropriate. Author Michael McDowell wrote many paperback horror originals (as well screenplays for Beetlejuice and The Nightmare Before Christmas) dealing with family curses and historical haunts, but Toplin seems unlike anything else in his oeuvre. Originally published a limited-edition hardcover by horror specialty publisher Scream/Press in 1985, it saw print again in paperback (seen above) in August 1991 thanks to Dell's Abyss imprint. The Abyss line of experimental and challenging horror fiction (see Kathe Koja's The Cipher) was a perfect home for this surreal first-person novel of a near-anonymous man living in a horrifying world that he perceives as strangely as if he were an alien on earth.

Toplin fits very few subcategories of horror fiction, and upon finishing I'm not entirely sure the word "Horror" on its spine is deserved; it's unsettling in places but not scary. But then I'm not sure what genre would be appropriate. Author Michael McDowell wrote many paperback horror originals (as well screenplays for Beetlejuice and The Nightmare Before Christmas) dealing with family curses and historical haunts, but Toplin seems unlike anything else in his oeuvre. Originally published a limited-edition hardcover by horror specialty publisher Scream/Press in 1985, it saw print again in paperback (seen above) in August 1991 thanks to Dell's Abyss imprint. The Abyss line of experimental and challenging horror fiction (see Kathe Koja's The Cipher) was a perfect home for this surreal first-person novel of a near-anonymous man living in a horrifying world that he perceives as strangely as if he were an alien on earth. With his obsessive, disaffected detailing of the geometry of place and thought, of numbering and organization, Toplin himself seems like a character out of J.G. Ballard's magnificent experimental "novel" from 1970, The Atrocity Exhibition. The symbolic nature of the corridors in his apartment seems just out of reach - a man with a mind such as this is probably adding up the degrees of corners and planes in his home to arrive at the date of the Apocalypse, or the day he will assassinate the President. In Toplin's case, he will instigate the death, and therefore freedom, of Marta, a horribly deformed waitress at his local greasy-spoon diner to give his life meaning.

With his obsessive, disaffected detailing of the geometry of place and thought, of numbering and organization, Toplin himself seems like a character out of J.G. Ballard's magnificent experimental "novel" from 1970, The Atrocity Exhibition. The symbolic nature of the corridors in his apartment seems just out of reach - a man with a mind such as this is probably adding up the degrees of corners and planes in his home to arrive at the date of the Apocalypse, or the day he will assassinate the President. In Toplin's case, he will instigate the death, and therefore freedom, of Marta, a horribly deformed waitress at his local greasy-spoon diner to give his life meaning.

The disfigurements of her birth were compounded with the ravages of disease. I saw them in her face. Her mouth was a running sore. Her bulging eyes were of difference colors. Her ears were slabs of flesh pillaged from anonymous victims of accidents. her nose was a bulging membrane filled with ancient purulence... beneath her uniform I sensed - I smelled- ever greater deformities. Her uniform, stained to a filmy translucence by God knew what manner of excretions, showed the irregularities of her skin beneath.

The motley cast of dingy, repellent, enigmatic characters is practically out of "Desolation Row," and McDowell intimates that they all might be either figments of Toplin's imagination or symbols for various aspects of it. Random street people run into the diner and harangue customers about pornography and government corruption. His coworkers seem to exist only to play a deadly practical joke on him that leaves him color-blind, but it's a situation into which Toplin could have gotten himself into. He consciously attempts to befriend Howard, a young deliveryman Toplin sees every day at work.

He must see the interiors of so many offices and many flats. In the doorway of how many livings rooms has Howard stood... into how many lives has Howard entered, albeit in the most peripheral fashion? Has he been affected by this experience with the apartments and offices of total strangers?

Howard's grandfather seems to be an insane old scholar, now locked in a room in the home they share. The nighttime streets are prowled by an ultimately violent street gang called Tempis Fugit. Marta's maintenance man is a hermaphrodite - or is he simply Howard in disguise? And you don't even want to know who Toplin has regular consensual sex with. Everything in Toplin is askew, deranged, crumbling, so much deformity beneath one roof he muses at one point. His occasional rants about effeminate men bring on the usual suspicion. He's paranoid, unreliable, solipsistic, monomaniacal - you know, quite mad.

This works in places, but reading Toplin in fits and starts breaks its spell; once I was reading 50 pages at a time its ghastly psychopathology was able to seep into my head... some. It only really captured me here and there and the ending was about as obscure as I'd anticipated. McDowell (pictured above) is a fine writer and I'm looking forward to reading his more traditional early '80s horror novels such as Cold Moon over Babylon and The Elementals, but I feel that Toplin is a bit underdone, maybe too abstruse for its own good. The paperback publisher has blown up the print so the book is 277 pages long; in its original hardcover it is 186 pages. The solarized illustrations in the middle of the book, by Harry O. Morris, a holdover from the hardcover, are a little too on-the-nose to be truly disturbing but are still creepy. And then again, how much time do you want to spend in the head of someone who thinks the slime built up in my testicles, and I made no effort to release it. I felt its slow poison seeping through my body?

This works in places, but reading Toplin in fits and starts breaks its spell; once I was reading 50 pages at a time its ghastly psychopathology was able to seep into my head... some. It only really captured me here and there and the ending was about as obscure as I'd anticipated. McDowell (pictured above) is a fine writer and I'm looking forward to reading his more traditional early '80s horror novels such as Cold Moon over Babylon and The Elementals, but I feel that Toplin is a bit underdone, maybe too abstruse for its own good. The paperback publisher has blown up the print so the book is 277 pages long; in its original hardcover it is 186 pages. The solarized illustrations in the middle of the book, by Harry O. Morris, a holdover from the hardcover, are a little too on-the-nose to be truly disturbing but are still creepy. And then again, how much time do you want to spend in the head of someone who thinks the slime built up in my testicles, and I made no effort to release it. I felt its slow poison seeping through my body?

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)

.JPG)

+back+cover.JPG)

+Cover+Ken+Barr.jpg)