Weren't there, among those creatures, faculties she envied? The power to fly, to be transformed, to know the condition of beasts, to defy death?... the monsters were forever. Part of her forbidden self. Her dark, transforming midnight self. She longed to be numbered among them.

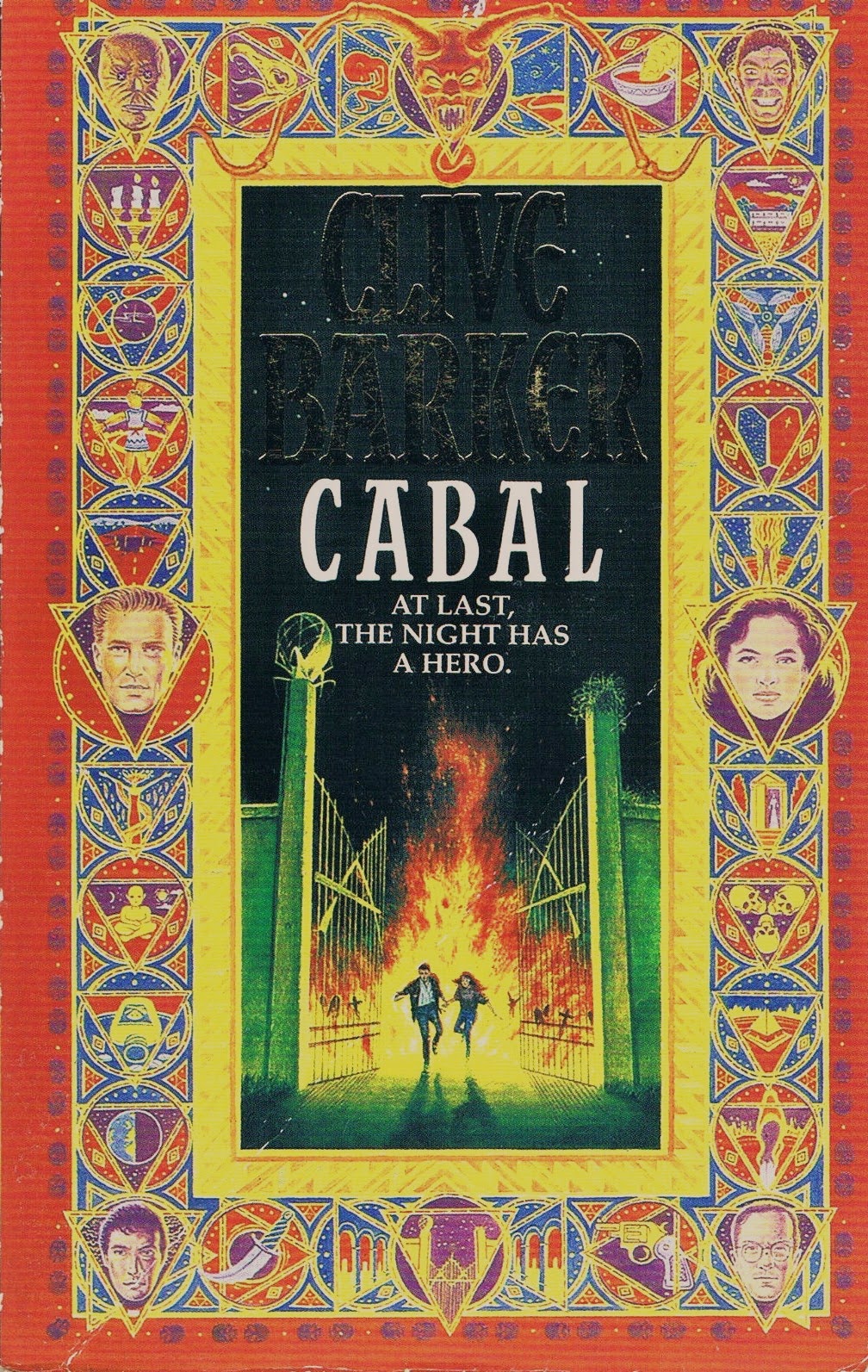

Another prime example of

Clive Barker's consistent concern with monsters and the humans that dwell in their midst,

Cabal came out at perhaps the height of his success as a bestselling horror author. The 250-page novella was published in hardcover in the US along with the stories from

Books of Blood Vol. VI, while in the UK it was issued as a standalone title. Then a year later Barker began adapting this work for the screen as

Nightbreed, the storied, troubled production of which probably most horror fans of that era are familiar with. I'd read

Cabal twice but oh so long ago: once before the film was out in early 1990 and once not long after. A couple weeks ago I watched the recently released

director's cut of

Nightbreed and afterward reread

Cabal. Not as a "compare and contrast" exercise, which is a bit too English Comp 101 for me, but the movie had gotten me thinking: how has a quarter century's passing affected my affinity for the Tribes of the Moon (a phrase found only in the film)? Would I still be as excited and eager about the Nightbreed as I am in this photo?

Clive Barker and me; he's signing my Nightbreed poster.

January 1991

Spoilers! Cabal is the story of Aaron Boone, a young man on the run from

his psychiatrist Dr. Decker, a secret madman who plans to blame Boone for

his own serial killer crimes. Boone is being chased by Lori, the woman he left but who loves him still. If all that's not enough, Boone is attempting

entry into a fabled world where the monsters live. It's a vast forgotten cemetery near an abandoned town called Midian in the Canadian wilds, a catacombed necropolis beneath the earth in which hide the monsters of myth and legend, exiled from a fearful, vengeful humanity. But Boone is not the monster Decker's convinced him he is... yet.

He'd heard the name of that place spoken maybe half a dozen times by people he'd met on the way through, in and out of mental wards and hospices, usually those whose strength was all burned up. When they called on Midian it was a place of refuge, a place to be carried away to And more: a place where whatever sins they'd committed--real or imagined--would be forgiven them. Boone didn't know the origins of this mythology nor had he ever been interested enough to find out. He had not been in need of forgiveness, or so he thought. Now he knew better...

Harper Collins, Toronto, 1989

Boone's entrance to Midian is foolhardy and near-fatal: a bite from a Breed member "more reptile than mammal" called Peloquin--who can instantly sense Boone's guiltless, Natural self--gives Boone a kind of immortality, which comes in handy when Decker brings the police force to Midian and they shoot Boone dead. But he's not dead.

Now, as a walking dead man, he's become the Breed, and escapes the morgue. But his return bodes unwell for the inhabitants of Midian, who fear he will reveal them to Man. Boone defies the laws of the Breed when he rescues faithful Lori from blood-hungry Decker outside Midian's gates, which causes all sorts of problems. However, here in horror Boone's truest self's revealed:

In Decker's presence he'd been proud to call himself monster: to parade his Nightbreed self. But now, looking at the woman he had loved and had been loved by in return for his frailty and his humanity, he was ashamed.

His will making flesh smoke, which his lungs drew back into his body. It was a process as strange in its ease as in its nature. How quickly he'd become accustomed to what once he'd once have called miraculous.

To make up for his folly Boone demands to see Baphomet, the Nightbreed god who created Midian as a haven for these creatures. Following Boone, Lori gets a glimpse of a column of flame and:

There was a body in the fire, hacked limb from limb... this was Baphomet, this diced and divided thing. Seeing its face, she screamed. No story or movie screen, no desolation, no bliss, had prepared her for the maker of Midian. Sacred it must be, as anything so extreme must be sacred. A thing beyond things. Beyond love or hatred or their sum, beyond the beautiful or the monstrous or their sum. Beyond, finally, her mind's power to comprehend or catalog.

This meeting is a moment out of all man's primitive religions: the holy

fire, the sacred other, that once seen cannot be unseen, and once experienced the

profane is transformed.

There is no going back. Boone is a Moses and Baphomet his Yahweh; prophecy foretold. Barker has always gotten good mileage out of this comparative mythology aspect of his fiction, mileage I'm always happy to travel. While Lovecraft parodied and satirized religious beliefs with his "Yog-Sothothery," Barker recognizes that humans have a need for transcendence, but not one that annihilates, one that transforms. Boone bravely embraces his true nature; he is no Outsider reaching out in cowering fear and touching a mirror.

And so the tale continues, and closes, with redneck cops--led by the truly odious Eigerman--and a gaggle of shotgun-wielding yahoos on loan from

Night of the Living Dead descending on Midian thanks, again, to Decker. He's set on killing Lori, who now knows his secret. He loathes the Breed, cannot wait to participate in their destruction:

"They were freaks,

albeit stranger than the usual stuff. Things in defiance of nature, to

be poked from under their stones and soaked in gasoline. He'd happily

strike the match himself." They rout the Breed in a final confrontation that will create a new enemy and destroy another. Boone is renamed Cabal--"an alliance of many"--by Baphomet and ordered to rebuild (

"You've undone the world. Now you must remake it"). Lori and Boone are reunited at last.

But the Nightbreed are not ended. Irony abounds, even until the very last line:

"It was a life." Lori's

words to Boone after he rescues her from death and gives her his Breed

balm (heh, and yes, he does this figuratively and literally) are,

"I'll

never leave you," which the astute reader will recognize as the words in

the opening paragraph, words Boone considers a lie. What does this irony mean? Barker knows how to

leave readers wanting more by undermining expectations; the tale ends just as it's beginning!

Fontana UK movie tie-in, 1990

In a 1989 Fangoria interview with journalist/author

Philip Nutman, Barker talked about the motivation in making

Cabal a novella:

"I wanted to do the reverse of what I did in Weaveworld,

which was to really cross the t's and dot the i's, give

every detail of psychology and so on. In Cabal I wanted

to present a piece of quicksilver adventuring in which

you were just seeing flashes of things, Boone, Lori,

the Breed, each character's psychology reduced to

impressions. Part of the fun for me was to write it in

short, sharp bites."

I quote this because it explains what at first I disliked about

Cabal on this reread: strokes were too broad; too much time giving

impressions and not specifics; characters were moved about like a kid

playing with action figures--so much to-ing and fro-ing! After the short sharp shocks of the

Books of Blood and the epically-drawn dark fantasy of

Weaveworld, maybe the novella format was not good idea. But as I read, Barker's writing grew in its

conviction; he's more adept

at the contradictions and ambiguities of murderers and marauders than

he is with the banalities of everyday life. Still, some frustrations:

Decker's psychopathy could have been expanded; the creepiest moments belong to him, like when Ol' Button Face, the glib nickname Decker has for

his killing mask/personality, chatters hungrily to him while it resides

in his briefcase. The conflict of his inhumanity versus that of the Nightbreed

is sketched in here and there, none more illuminating than when Barker

writes of Decker:

"The thought of his precious Other being confused with the degenerates of Midian nauseated him." Decker is a fascinating character; the witless police not so much.

Fans of the film looking for bizarre monstrosities will have to be satisfied with only glimpses of the

Nightbreed. Unlike some of the detailed

creatures that inhabited Barker's earlier short stories like "Rawhead Rex,"

"In the Skins of the Fathers," or "Son of Celluloid," the reader is given mostly impressions. With a

surrealist's eye Barker gives us intriguing hints but doesn't belabor

the descriptions. When Lori first descends into Midian:

...was

it simply disgust that made her stomach flip, seeing the stigmatic in

full flood, with sharp-toothed adherents sucking noisily at her wounds?

Or excitement, confronting the legend of the vampire int he flesh? And

what was she to make of the man whose body broke into birds when he saw

her watching? Or the dog-headed painter who turned from his fresco and

beckoned her to join his apprentice mixing paint? Or the machine beasts

running up the walls on caliper legs? After a dozen corridors she no

longer knew horror from fascination. Perhaps she'd never known.

1989 Pocket Books edition

Yes, Barker's

mantra has always been thus. In the monstrous there is beauty; the

normal course of daily things is a horror. But I wanted more.

Cabal works better if one considers it as allegory, as fable, and its politics are a liberal dream: evil is not evil, it's

an alternative lifestyle! Witness the callous crude cruelties of doctor,

cop, and priest: the first is a psychopath literally wearing a mask;

the second an egomaniac concerned only with his brand of law, order, and

notoriety; the last is a hypocrite. The undoing will be at

the hands of these traditional authorities; it is

they who will squeeze

the life out of the untamed, the unwanted, even the undead.

Cabal ends clearly stating that the enemies are still active, still enraged, still stung by humiliation and eager to bring a comeuppance.

Poseidon Press 1988 US hardcover

I guess I'm saying there's a theoretical distance in

Cabal which prevents me from really, truly enjoying it the way I do so much of Barker's other work. Maybe it's the movie, which I like all right in its new incarnation but have never been overly fond of (although this version is a more faithful adaptation,

Nightbreed remains irredeemably cheesy in a way

Cabal is not), intruding upon my imagination; I can't at all recall how I envisioned the story before its film adaptation. And it reads, and ends, like a prequel. This has been a problem with Clive Barker since, well, since 1988. He's always intended to continue the story of

Cabal. To continue the story began in

The Great and Secret Show. And

Galilee. And

Abarat. Later this year we'll finally get

The Scarlet Gospels, which apparently concludes the stories Harry D'Amour and Pinhead, an apotheosis of two aspects of Barker's art. His ambition might outreach his vision, his health, and dare I say it, his life. But again, it pays to see

Cabal as a fable, a beginning, a story

for us

about us: fans of the Breed

are the Breed,

"The un-people, the anti-tribe, humanity's sack unpicked and sewn together again with the moon inside." That is a story that continues, and continues, and continues.

Barker '88

+Cover+Kirk+Reinert.jpg)