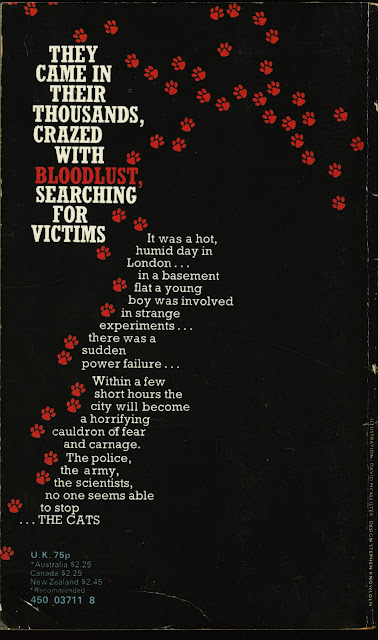

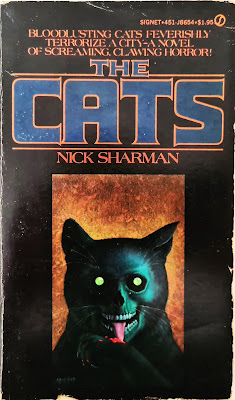

Scott Grønmark was his name and writing pulp horror paperbacks under the pseudonym "Nick Sharman" was his game. Born in Oslo, Norway, in 1952, he was working in the PR department of New English Library (which is why of course he had to use a pseudonym) when he began his published career with The Cats. It was originally published by NEL in 1977 (below), and then by Signet in America in May 1979. Subsequently he wrote six or seven novels, only one under his real name. Notoriety came Grønmark's way some years back when internet wags postulated that he was the person responsible for the infamous sleaze-horror "classic" Eat Them Alive, which wasn't so; you can read his response here.

An early entry into the animal attack publishing craze led, of course by Jaws and The Rats, The Cats offers up most, but not all, of the usual template, even though the subgenre had only been going on a couple years by 1977. Most characters are irritable, stuffy, smug, and/or macho. Or American, for no reason I could discern. Victims run the gamut of British society, briefly introduced, quickly dispatched. Requisite cynicism about politicians while the mighty military comes in swinging their dicks. Science is responsible for the poor kitties' condition. There isn't even a love interest, believe it or not, but there is an attempted rape—about the only woman who appears (the assault is prevented at the last second). Two sets of estranged fathers and sons lend a tad bit of character conflict. One human is afflicted by the same disease as the cats have, maybe there's a psychic connection too, an addition I found intriguing.

I wish Grønmark had attempted to give his rampaging cats a smidge of personality. We all know cats in our personal lives who are more interesting than some people in our social circles. Imagine if he'd spent just a chapter on the creatures themselves, even just a couple kitties, perhaps even inspired by then-bestselling juggernaut Watership Down—recall how Richard Adams did marvels with cuddly rabbits! That would've given this slight 154-page novel some much needed ballast as well as some empathy for innocent animals.

But that's not what this book is or wants to be. Despite several vivid attacks early on, Grønmark doesn't seem to have much energy to inject his tale with anything but the driest essentials. There's little spark in the proceedings, not even anything but the most workmanlike approach to feline slaughter. Prose is competent, serviceable, but lacking any real juice. He simply keeps the narrative going faster and faster but with diminishing results, I mean I've kind of already forgotten the specifics of the climax, such as it is, and the cute yet utter by-the-numbers final paragraphs fail to surprise. I did like the guy who tries in vain to fight back against the beasts with acid, is still overwhelmed, and croaks, as his last words, "Oh well, you can't win 'em all."

Previous Grønmark books I've read, The Surrogate and Childmare, were more entertaining, written with a bit more skill and conviction. As noted, The Cats was Grønmark 's debut novel, and I guess he simply didn't have the chops yet. (At least it led to a successful writing career, I'll give it that; he died in 2020 aged 68.) Unfortunately, I found The Cats lackluster, offering nothing fresh to the all-too-common cliches of animal-attack literature. If you're a collector, you'll want the Signet edition with that spectacular Don Ivan Punchatz cover, but unless you're an animal-attacks obsessive, you can probably leave the book on the shelf.

As he lay on the ground he could see people jumping from the smashed upper windows of the double-decker bus, and then his eyes locked with those of the black cat. Its jaws gaped for a ghastly instant before its teeth rammed straight through the flesh of the man's nose and crunched into the hard knuckle of gristle underneath.