Neither Modern Masters paperback cover offers much to catch a prospective reader's eye (the Ace '82 resembles a Hitchcock crime anthology) and the only reason I picked up the '88 edition was because it was in pristine condition. Lucky too because inside are several standouts that aren't available anywhere else.

The unexpected star of this anthology is not, as one might think, the long Stephen King tale that starts it off ("The Monkey," which headlined Skeleton Crew [1985]; good but not great King), but the sole short story from one George A. Romero. "Clay" bears no resemblance to his zombie movies, but there are similarities to his excellent 1977 film Martin (and fine with me; Martin is my favorite Romero flick). With a careful and a vivid pen, Romero lays out a tale of two men in the New York City of decades ago: one a priest and one a neighborhood drunk. Compare and contrast: If the priest had ever visited Tippy's brownstone under the el, if he'd ever gone up to the third floor, he would have seen the beast of the city at its most dissolute... The matter-of-fact descriptions of horror and perversion elevate "Clay" to the top rank; one wonders what if Romero had written the story as a screenplay...!

These days—if ever—I'm not crazy about the threat of rape used as a generic horror device, but hey, this was some three decades ago, times were simpler, so I take it as it comes. Written without any whiff of exploitation, "The Face" by Jere Cunningham speaks of secret selves to maintain sanity, but perhaps that's where we hide our madnesses as well. Robert Bloch's "In the Cards" is a terrible example of his old-man puns in short-story form. In Gahan Wilson's bit of playful metafiction, "The Power of the Mandarin," a mystery writer has created the ultimate villain for his Sherlockian detective—and doomed himself in the process. "The Root of All Evil" boasts a banal and cliched title but is a serviceable tale of ancient myths in the modern world thanks to Graham Masterton. Enjoyed William Hallahan's returns to the sort of astral projection he utilized for his 1978 occult thriller Keeper of the Children in "The New Tenant"; brief and to the point and dig that ice-cold climax.

Long-time SF/F/horror scribe William F. Nolan's piece was originally published in 1957, which I didn't now as I began "The Small World of Lewis Tillman." "What is this?!" I thought to myself as I read, "some shameless rip-off of I Am Legend?" Except instead of a last man on earth facing a vampire horde, Nolan's protagonist faces a horde of children. I honestly don't know which would be worse.

"Absolute Ebony" by Felice Picano (above) is a another gem. Set in a well-wrought 19th century Rome, it's about an American painter's discovery of the "blackest of the black," a charcoal so black it is like peering into infinity, somehow pulsing alive with the very negation of matter. This revolutionzies the man's art, but is cause for greater concerns. "Absolute Ebony" predates David Morrell's "Orange is for Anguish, Blue for Insanity" and the surreal mind-bending of Thomas Ligotti as it mines similar ideas and images. Despite penning some lurid thrillers in the 1970s and early '80s, Picano is not associated with the genre; his prose has a confident panache often lacking in horror fiction which makes the story a highlight of the anthology.

Wasn't too taken with Ramsey Campbell's contribution, "Horror House of Blood." A couple lets a horror film crew shoot a few scenes in their home, and subtle weirdness ensues. I couldn't figure out what was happening in some places due to Campbell's opaque stylings but I do like the effect of ending the story just before the horror begins.

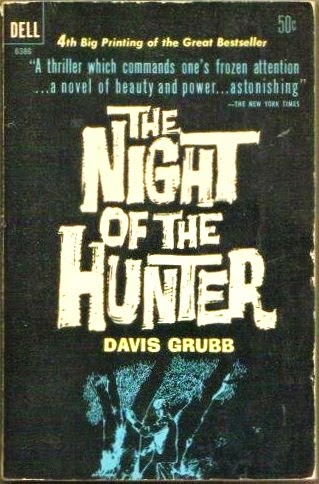

"The Siege of 318" is Davis Grubb's (above) tale of an Irish immigrant family living in West Virginia in the 1930s. Young master Benjy receives, as a gift from an uncle in Kilronan, an enormous crate of toy soldiers and attendant vehicles and weapons, enough even to reenact the Great War. At first father Sean approves: "'Tis time you learned the lessons of life's most glorious game." Except of course it goes slowly downhill as the "game" obsesses Benjy and enrages his father. You may be reminded of King's "Battleground" from Night Shift but this story is subtler, better written, with a tinge of world-weary resignation about the world's historic horrors that really chills. Another gem!

Two writers I'm not crazy about have two stories worth a read. "The Champion" from Richard Laymon is a competent bit of undeserved turnabout that wouldn't have seem out of place as an episode of Hitchcock Presents. Not a whiff of his retrograde approach to horror but features his trademark lack of believability. Laymon never bothers to convince a reader that the impossible is possible; he simply assumes it because, hey, this is horror fiction, right? Robert McCammon's "Makeup" I recall reading in his 1990 collection Blue World and thought it was merely kinda okay; this time I kinda enjoyed it more: loser crook in Hollywood inadvertently steals an old makeup case that once belonged to horror movie star Kronsteen (also featured in his novel They Thirst) and when he smears some on his face he—well I won't ruin it for ya.

Howling author Gary Brandner presents another type of body transformation in "Julian's Hand," a surprisingly straight-forward story about an accountant growing a hand under his arm. I liked it right up till its unexpectedly illogical conclusion. I mean, it just doesn't work, and an alternate ending, involving a coworker with whom the accountant has an affair, was up for grabs (pun intended, you'll see). There could've been a strange and happy ending instead of the lazy twist Brandner employs.

Another story marred by its ending is "A Cabin in the Woods" from John The Searing Coyne (above). It's a solid work of literally growing unease when the titular domicile is overrun by a fungus. The only problem is that the final line of the story, creepy as it is, is entirely too reminiscent of King's "I Am the Doorway." (And if you haven't read that story, you've got some treat waiting for you!)

Despite a few so-so fictions and lackluster cover art in all editions, Modern Masters of Horror is worth seeking out for the Romero and Picano, Grubb and Hallahan stories. I don't think you'll be too disappointed with the other stories included either. The "Scaries" indeed.

The unexpected star of this anthology is not, as one might think, the long Stephen King tale that starts it off ("The Monkey," which headlined Skeleton Crew [1985]; good but not great King), but the sole short story from one George A. Romero. "Clay" bears no resemblance to his zombie movies, but there are similarities to his excellent 1977 film Martin (and fine with me; Martin is my favorite Romero flick). With a careful and a vivid pen, Romero lays out a tale of two men in the New York City of decades ago: one a priest and one a neighborhood drunk. Compare and contrast: If the priest had ever visited Tippy's brownstone under the el, if he'd ever gone up to the third floor, he would have seen the beast of the city at its most dissolute... The matter-of-fact descriptions of horror and perversion elevate "Clay" to the top rank; one wonders what if Romero had written the story as a screenplay...!

Romero & King, early 1980s

These days—if ever—I'm not crazy about the threat of rape used as a generic horror device, but hey, this was some three decades ago, times were simpler, so I take it as it comes. Written without any whiff of exploitation, "The Face" by Jere Cunningham speaks of secret selves to maintain sanity, but perhaps that's where we hide our madnesses as well. Robert Bloch's "In the Cards" is a terrible example of his old-man puns in short-story form. In Gahan Wilson's bit of playful metafiction, "The Power of the Mandarin," a mystery writer has created the ultimate villain for his Sherlockian detective—and doomed himself in the process. "The Root of All Evil" boasts a banal and cliched title but is a serviceable tale of ancient myths in the modern world thanks to Graham Masterton. Enjoyed William Hallahan's returns to the sort of astral projection he utilized for his 1978 occult thriller Keeper of the Children in "The New Tenant"; brief and to the point and dig that ice-cold climax.

Long-time SF/F/horror scribe William F. Nolan's piece was originally published in 1957, which I didn't now as I began "The Small World of Lewis Tillman." "What is this?!" I thought to myself as I read, "some shameless rip-off of I Am Legend?" Except instead of a last man on earth facing a vampire horde, Nolan's protagonist faces a horde of children. I honestly don't know which would be worse.

"Absolute Ebony" by Felice Picano (above) is a another gem. Set in a well-wrought 19th century Rome, it's about an American painter's discovery of the "blackest of the black," a charcoal so black it is like peering into infinity, somehow pulsing alive with the very negation of matter. This revolutionzies the man's art, but is cause for greater concerns. "Absolute Ebony" predates David Morrell's "Orange is for Anguish, Blue for Insanity" and the surreal mind-bending of Thomas Ligotti as it mines similar ideas and images. Despite penning some lurid thrillers in the 1970s and early '80s, Picano is not associated with the genre; his prose has a confident panache often lacking in horror fiction which makes the story a highlight of the anthology.

Wasn't too taken with Ramsey Campbell's contribution, "Horror House of Blood." A couple lets a horror film crew shoot a few scenes in their home, and subtle weirdness ensues. I couldn't figure out what was happening in some places due to Campbell's opaque stylings but I do like the effect of ending the story just before the horror begins.

"The Siege of 318" is Davis Grubb's (above) tale of an Irish immigrant family living in West Virginia in the 1930s. Young master Benjy receives, as a gift from an uncle in Kilronan, an enormous crate of toy soldiers and attendant vehicles and weapons, enough even to reenact the Great War. At first father Sean approves: "'Tis time you learned the lessons of life's most glorious game." Except of course it goes slowly downhill as the "game" obsesses Benjy and enrages his father. You may be reminded of King's "Battleground" from Night Shift but this story is subtler, better written, with a tinge of world-weary resignation about the world's historic horrors that really chills. Another gem!

Two writers I'm not crazy about have two stories worth a read. "The Champion" from Richard Laymon is a competent bit of undeserved turnabout that wouldn't have seem out of place as an episode of Hitchcock Presents. Not a whiff of his retrograde approach to horror but features his trademark lack of believability. Laymon never bothers to convince a reader that the impossible is possible; he simply assumes it because, hey, this is horror fiction, right? Robert McCammon's "Makeup" I recall reading in his 1990 collection Blue World and thought it was merely kinda okay; this time I kinda enjoyed it more: loser crook in Hollywood inadvertently steals an old makeup case that once belonged to horror movie star Kronsteen (also featured in his novel They Thirst) and when he smears some on his face he—well I won't ruin it for ya.

Howling author Gary Brandner presents another type of body transformation in "Julian's Hand," a surprisingly straight-forward story about an accountant growing a hand under his arm. I liked it right up till its unexpectedly illogical conclusion. I mean, it just doesn't work, and an alternate ending, involving a coworker with whom the accountant has an affair, was up for grabs (pun intended, you'll see). There could've been a strange and happy ending instead of the lazy twist Brandner employs.

Another story marred by its ending is "A Cabin in the Woods" from John The Searing Coyne (above). It's a solid work of literally growing unease when the titular domicile is overrun by a fungus. The only problem is that the final line of the story, creepy as it is, is entirely too reminiscent of King's "I Am the Doorway." (And if you haven't read that story, you've got some treat waiting for you!)

Despite a few so-so fictions and lackluster cover art in all editions, Modern Masters of Horror is worth seeking out for the Romero and Picano, Grubb and Hallahan stories. I don't think you'll be too disappointed with the other stories included either. The "Scaries" indeed.