Whew, where to begin?

The Girl Next Door has, in the near quarter-century since its publication, achieved a notoriety few other modern horror novels can match. It was the third novel from

Dallas Mayr, written under his now-famous pseudonym

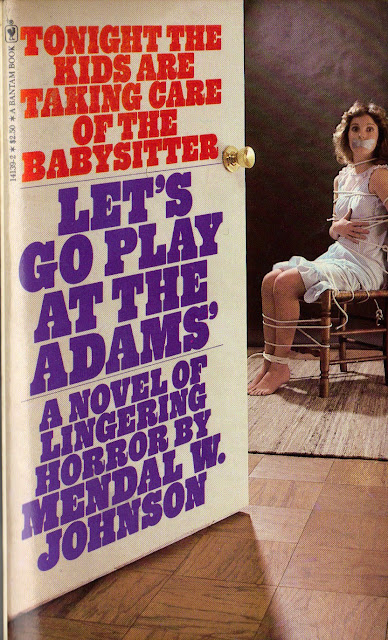

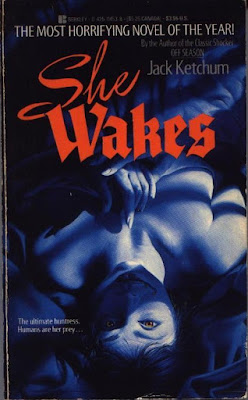

Jack Ketchum. Now, I hadn't even heard of Ketchum or this book until the last five or six years, I guess around the time it was reprinted by Leisure Books. None of his other vintage-era books,

Off Season (1980)

, Cover (1987), or

She Wakes (1989), look familiar to me, and he didn't start getting nominated for the Bram Stoker Award till the mid-'90s by which time I'd stopped reading modern horror, so it seems the book's reputation grew as a result of the reprints and the internet. Which isn't to say it isn't deserved, because it is. Oh is it.

The Girl Next Door

The Girl Next Door is loosely based on the mind-curdling 1965 torture/murder case of 16-year-old

Sylvia Likens. While some readers, if not most, may balk at the depths to which Ketchum goes in "recreating" what happened, he fills out his book with enough convincing details so that the matter never seems exploited or cheapened. Ketchum is, for better or worse, a reliable and insightful guide as he delves into these places of heartlessness and cruelty found not in the supernatural or the extraterrestrial but, well, literally, next door. He presents it all in plain strong prose that neither titillates nor overstates; he is in command of his words and images in a way a cheap and foolish writer - whose ranks in the horror genre are legion - could only ever dream.

It's told in first person by David, 30 years after the horrific events, which occurred when he was about 12 years old. His regret and sadness and confusion set everything in motion. Pondering his three failed marriages, he attempts to tell the story. The whole story, without faltering, of when teenage Meg Loughlin and her 11-year-old sister Susan come to live with David's next-door neighbors, the Chandlers, after the girls' parents are killed in a car crash. Ruth Chandler, a distant relation to the Loughlin girls, middle-aged, a heavy smoker and drinker but not without her looks, is well-known to all the kids living on the tree-lined, dead-end street as the parent who will give beers to them while they hang out with her own pre-teen sons Willie, Woofer, and Donny. Her husband left the family years earlier, running off with another woman (which explains some of her future behavior towards Meg).

David becomes smitten with Meg in a not-quite-romantic way; he's three years younger than her anyway, but spends some nice, memorable moments with her early in the story. Cute, sweet, well-done, a yearning without knowing quite what one is yearning for. Which makes the following descent the more upsetting. When the boys try from a tree outside her window to spy on Meg undressing and are denied it, David's response is bitter and black:

I could have smashed something. I could have torn that house to bits. That surprised me; it could have come straight from one of

James Ellroy's noir crime novels, for sure (more on Ellroy later).

Overlook Connection Press 2002

Overlook Connection Press 2002

The most difficult thing about reading the book is that you know where it's going. When it happens - when Ruth's abuse of Meg begins - it happens fast but it also happens slow, if you know what I mean. The pall of inescapable doom threads through the early narrative, a malevolence hovering over every scene of innocence. It waits. It waits. It will not be denied. There is simply no other word for what happens: torture, physical and mental and sexual. First restricted from eating on her own, Meg then physically defies Ruth in front of David and other boys. Outraged beyond measure, and with the help of her sons, Ruth ties her up in the abandoned bomb shelter in the basement and the horror starts. This goes beyond the "horror" genre into what

Douglas Winter talked about: that horror is not a genre, but an

emotion. An emotion that's going to settle in and stay awhile.

There are things you know you'll die before telling, things you know you should have died before ever having seen.

I watched and saw.

Since Ketchum structures the novel as a troubled adult looking back on a traumatic occurrence in his past,

The Girl Next Door reminded me of

Stephen King's novella "The Body" (found in

Different Seasons from 1982, and the basis for

Stand By Me. I guess I don't need to tell you that). Still utterly haunted by Ruth, adult David slips in at times and explains

why this or

why that, and especially how he was able to stand by while Ruth orchestrated such horror and why his friends went along. And it simply makes sense. Kids are powerless. Kids are

supposed to endure humiliation. Adults control every avenue of kids' lives. I find this especially convincing in children growing up in the early 1960s, when adult authority was divine order. The divide between the world of children and the world of adults was vast and unbridgeable. Why didn't he

try to tell? Meg actually does, once, to a cop who doesn't take her very seriously. This causes the boys to begin to feel a vague contempt for her. (Let's not forget Matt Dillon's immortal words in that teenage riot classic

Over the Edge:

"A kid who tells on another kid is a dead kid"). Because, as David reminds us:

Shit, [adults] could just dump is in a river if they wanted to. We were just kids. We were property. We belonged to our parents, body and soul. It meant we were doomed in the face of any real danger from the adult world and that meant hopelessness, and humiliation and anger.

The kids know better than to try to tell. Telling is bullshit. Telling makes things worse. Telling is an insult and a cheat. The kids even play what they call "the Game," a questionable past-time which, when Ruth learns of it, wants to play. And that makes it all even easier for the kids to go along... it's all a game, right? If Ruth says it's okay, well, it's okay for the kids no matter what is inflicted upon flesh (

"You said that we could cut her, Mrs. Chandler"). This is when David admits he

"flicked a slow mental switch [and] turned off on [Meg] entirely." Because

How could she be so dumb as to think a cop was going to side with a kid against an adult, anyway? So I think Ketchum does a dead-on job of getting into a mindset that would become a willing witness to Hell, even drink a Coke and play crazy eights while doing so. It is

totally believable.

2005 Leisure Books reprint

2005 Leisure Books reprint

So other neighborhood kids get involved and it's all just normal, they're spending boring summer afternoons in the basement of the Chandlers', hey, didja hear, they got a girl down there and they...

do stuff to her. When describing the sniggering remarks and dispensed humiliations and then the torturous cruelty in unflinching detail, Ketchum is carefully dispassionate, even when things turn, unsurprisingly, sexual for the young boys, as well as for Ruth and even a young neighborhood girl (at first Ruth restricts the boys from touching Meg after she's been stripped, not because molestation or rape is wrong but... because who knows what

diseases this

whore has. Did you just feel your throat close up? Good). He has David wonder if it all would have happened had Meg

not been so pretty, had her body not been young and health and strong, but ugly, fat, flabby. Possibly not. The inevitable punishment of the outsider. But he reconsiders as he looks back on it:

But it seems to me more likely that it was precisely because she was beautiful and strong, and we were not, that Ruth and the rest of us had done this to her. To make a sort of judgment on that beauty, on what it meant and didn't mean to us.

Notice it says 'Terror,' not 'Horror'

Notice it says 'Terror,' not 'Horror'

It's this kind of insight that allows

Girl Next Door to work so well when you might think it couldn't: This is

true, this is how people who do these things

think. Debase, degrade, deflower. Once the words

I FUCK FUCK ME are burned onto her stomach - yes, you read that right - it's as if the boys lose interest; Meg has been reduced to a nothing. David tries to help her escape, and he fails. He tries to tell his father, then his mother, but cannot find the words to express something so... so. I mean, could you? Knowing you knew the whole time? David realizes he's the only one who has the imagination to conceive of the enormity of what's going on. I think that's what makes this book stand out from other "extreme" horror novels. The darkness may be complete, but it is true and real.

You may not be surprised to learn that I read

The Girl Next Door in a one-sitting white-heat rush, utterly compelled and spellbound, my eyes burning and wet by the end. I could feel a thick sadness in my chest and shoulders. But it's not without its faults, and I can't really go into the major one because it's a spoiler, but I understand it. I do. I've seen it in other books and films too. Can't really blame Ketchum either, I suppose. But none of the faults are the result of the subject matter or the graphic detail; this is an "extreme" novel done right, with an understanding and an honesty I found utterly sincere.

Look at it again, in case you forgot how dumb it was

Look at it again, in case you forgot how dumb it was

This is no tawdry paperback filled with high-school horror hijinks, as the clueless cover implies; there is no fun nor ridiculous cheese. In fact, that Warner Books cover art is one of the most insidious of paperback horror covers ever, an affront to both readers and the book itself (I don't blame artist

Lisa Falkenstern; it's likely she had no idea what cover she was illustrating). Who the fuck okayed it? Someone who doesn't give a shit about books, that's for sure.

In

some of the Amazon reviews I skimmed over after finishing I saw that many people hated the fact that Ketchum fictionalized the Likens case, but so what? What Ketchum does with the novel is quite similar to what Ellroy did with

The Black Dahlia: take a real-life case of murderous savagery and fictionalize it, inventing characters so as to probe the psychology of those involved in a way unavailable to us normally, to attempt an understanding of the weakness, the fear, the rage, that could lead to such incomprehensible acts. In this respect Ketchum's book has more in common with crime fiction than it does with horror fiction. Which is absolutely fine with me. Horror fiction or crime novel or a hellish concoction of both, or perhaps something else entirely,

The Girl Next Door gets my highest, but most reserved, recommendations.

+ISBN+0532152581.jpg)

+Cover+Kirk+Reinert.jpg)