Another installment of Fangoria mag's vintage book reviews, thanks to TMHF reader Patrick B. Authors should be familiar to horror fans: Joe Lansdale, Whitley Strieber, Michael Talbot, Rex Miller, and Thomas Monteleone. And I myself have reviewed three of these titles: Lansdale's Nightrunners, Talbot's Bog, and Miller's Slob.

Showing posts with label whitley strieber. Show all posts

Showing posts with label whitley strieber. Show all posts

Sunday, December 10, 2017

Saturday, October 31, 2015

Halloween Horrors, ed. by Alan Ryan (1986): Midnight... All Night

Happy Halloween, one and all! On this day of days I offer up a mixed bag of treats: Halloween Horrors (Charter Books/Oct 1987), one of Alan Ryan's several horror anthologies from the 1980s. Each short story is set at Halloween, of course, which allows for mining of all its myth and legend for the background details. You'll recognize all the familiar faces tonight, masked or unmasked, peering out at you from the pages, eager to have you step inside for a surprise, take one, won't you, or two, maybe three or more...

First up is "He'll Come Knocking at Your Door" by Robert McCammon. I've read this one before, in his 1990 anthology Blue World. It has a decent setup and payoff (intimate payment for townspeople's good fortune required by... someone) but, again, suffers from what I like least about McCammon: his square, earnest, almost dopey style; he's the John Denver of '80s horror. If he just took his gloves off more often, like he does in the stories final images—and even those could've been honed to a sharper edge–I'd like his stuff more. Ah well. On to "Eyes" from Charles L. Grant, a writer I can appreciate in the abstract but in the literal act of reading his stories, not always. But here his allusive, understated style fits a tale of grief and guilt and horror wrapped up tight together. A father can't forget or forgive when it comes to the death of his disabled son. The kicker is ironic, tragic, unshakeable. I think I'm gonna call this kinda thing heartbreak horror.

Whitley Strieber's "The Nixon Mask" is a droll

satire of that ol' crook Richard Nixon. As a peek into the machinations

of high office it's kind of funny, but Tricky Dick's paranoia gets the

best of him. I liked the tone of this one, absurdist humor turning into

horror, Ballardian big deals going on and on that have nothing to do with the people supposedly served and in fact the Watergate break-in is okayed on this eve. What happens when Dick Nixon wears a Dick Nixon mask? Oh, it's riddle wrapped in a mystery inside an enigma. I dug this one myself but I don't know how much mileage it'll have to a reader born after, say, the Carter administration. "Samhain Feis" by Peter Tremayne delves into Celtic

Halloween lore, has some nice scenery in the desolate Irish

countryside, a bit of deserved comeuppance in the end. No biggie.

"Trickster," from Steve Rasnic Tem, hits true emotional notes absent from other works here. A man mourns his dead brother, who from childhood was an incorrigible practical joker, distrusted by his own family thanks to truly horrible pranks (like pretending to be dead or even pretend-killing a baby relative. Hilarious!). Murdered on Halloween night a year earlier, our protagonist reminisces about how their lives growing up and growing apart. This Halloween he thinks—improbably, impossibly—he sees his brother out cavorting in a Halloween parade in San Francisco, where he'd died, and spends a hallucinatory night chasing after this phantom. "Trickster" feels like a story about real people, written by someone who's been there. It's sad at moments and that final trick really stings. Another case of heartbreak horror.

Editor Ryan's own contribution, "The Halloween House," doesn't display the careful sophistication of his other tales I've enjoyed; I suppose that wouldn't have fit this story of randy teens exploring a haunted house. An original idea there at the end, absurd even, but some nice horror imagery of a house, er, melting; otherwise it's as trite as its title. Guy N. Smith's "Hollow Eyes" gets a big no from me, some old dad complaining about his daughter's shifty, ugly boyfriend, searching for them during a Halloween rave-up, all wrong, no go, return to sender. "Three Faces of the Night" is Craig Shaw Gardner's ambitious and complex tale, told in three time frames, of love and college parties. The two don't mix.

"Pumpkin" from crime writer Bill Pronzini (pictured) delves into Halloween and harvest lore, not bad but not memorable.

Weird Tales scribe and HPL pal Frank Belknap Long gives us "Lover in the Wildwood," a tale of criminal lust in the backwoods; somewhere I can here the Crypt Keeper cackling and I wish someone would just shut him up. "Apples" is Ramsey Campbell's minor chiller about kids stealing fruit from an old man's garden. Campbell gets kids' dynamics right and the climax offers a nice frisson of nausea and creepiness, I mean I hate raw apples too (She'd spat out the apple and goggled at it on the floor Something was squirming in it). Not one of Campbell's best but a highlight of this anthology. The concluding story is from Robert Bloch, is a mean-spirited little gem of a neighborhood's trick-or-treat session gone horribly wrong. "Pranks" seems light-hearted at first but grows in menace till its great reveal removes all doubt of malicious intent.

Okay then, now for the final trick: for my money the star of this Halloween Horrors is Michael McDowell's (pictured above) "Miss Mack." The first of his few short stories, it is as sure and capable as any of his novels, simply condensed to an essence of cruel terror. I read it several years ago and it's haunted me ever since, which is surprisingly rare. Our Miss Mack is a beloved schoolteacher in Pine Cone, Alabama (also the setting of The Amulet) who befriends young Miss Faulk, recently hired by Principal Hill. But Principal has designs on this lovely innocent girl and cannot bear the fast, intimate friendship between the two women. Stoked by jealousy and, okay, yes, the occult secrets of his mother, Principal Hill puts a hex on Miss Mack. McDowell writes so well, his quiet evocation of locale and character so confident and matter-of-fact, you won't want the story to end. And in a way it doesn't. The final sickening, maddening horror upends all human notions of time and place, and without those, what are we? Lost in a night that never ends looking for a place that does not exist. When she waked, it was night—still Halloween night. "Miss Mack" has become a favorite of mine from the '80s era.

While enjoyable overall, I do wish Halloween Horrors had a few more tricks to play on readers; many of the stories are slight, mild, unremarkable. Still, a cheap copy is worth searching for, as a couple treats indeed have a razor blade tucked within...

1988 Sphere paperback, UK

First up is "He'll Come Knocking at Your Door" by Robert McCammon. I've read this one before, in his 1990 anthology Blue World. It has a decent setup and payoff (intimate payment for townspeople's good fortune required by... someone) but, again, suffers from what I like least about McCammon: his square, earnest, almost dopey style; he's the John Denver of '80s horror. If he just took his gloves off more often, like he does in the stories final images—and even those could've been honed to a sharper edge–I'd like his stuff more. Ah well. On to "Eyes" from Charles L. Grant, a writer I can appreciate in the abstract but in the literal act of reading his stories, not always. But here his allusive, understated style fits a tale of grief and guilt and horror wrapped up tight together. A father can't forget or forgive when it comes to the death of his disabled son. The kicker is ironic, tragic, unshakeable. I think I'm gonna call this kinda thing heartbreak horror.

Strieber: Hates Nixon

"Trickster," from Steve Rasnic Tem, hits true emotional notes absent from other works here. A man mourns his dead brother, who from childhood was an incorrigible practical joker, distrusted by his own family thanks to truly horrible pranks (like pretending to be dead or even pretend-killing a baby relative. Hilarious!). Murdered on Halloween night a year earlier, our protagonist reminisces about how their lives growing up and growing apart. This Halloween he thinks—improbably, impossibly—he sees his brother out cavorting in a Halloween parade in San Francisco, where he'd died, and spends a hallucinatory night chasing after this phantom. "Trickster" feels like a story about real people, written by someone who's been there. It's sad at moments and that final trick really stings. Another case of heartbreak horror.

1986 Doubleday hardcover

Editor Ryan's own contribution, "The Halloween House," doesn't display the careful sophistication of his other tales I've enjoyed; I suppose that wouldn't have fit this story of randy teens exploring a haunted house. An original idea there at the end, absurd even, but some nice horror imagery of a house, er, melting; otherwise it's as trite as its title. Guy N. Smith's "Hollow Eyes" gets a big no from me, some old dad complaining about his daughter's shifty, ugly boyfriend, searching for them during a Halloween rave-up, all wrong, no go, return to sender. "Three Faces of the Night" is Craig Shaw Gardner's ambitious and complex tale, told in three time frames, of love and college parties. The two don't mix.

"Pumpkin" from crime writer Bill Pronzini (pictured) delves into Halloween and harvest lore, not bad but not memorable.

Weird Tales scribe and HPL pal Frank Belknap Long gives us "Lover in the Wildwood," a tale of criminal lust in the backwoods; somewhere I can here the Crypt Keeper cackling and I wish someone would just shut him up. "Apples" is Ramsey Campbell's minor chiller about kids stealing fruit from an old man's garden. Campbell gets kids' dynamics right and the climax offers a nice frisson of nausea and creepiness, I mean I hate raw apples too (She'd spat out the apple and goggled at it on the floor Something was squirming in it). Not one of Campbell's best but a highlight of this anthology. The concluding story is from Robert Bloch, is a mean-spirited little gem of a neighborhood's trick-or-treat session gone horribly wrong. "Pranks" seems light-hearted at first but grows in menace till its great reveal removes all doubt of malicious intent.

Okay then, now for the final trick: for my money the star of this Halloween Horrors is Michael McDowell's (pictured above) "Miss Mack." The first of his few short stories, it is as sure and capable as any of his novels, simply condensed to an essence of cruel terror. I read it several years ago and it's haunted me ever since, which is surprisingly rare. Our Miss Mack is a beloved schoolteacher in Pine Cone, Alabama (also the setting of The Amulet) who befriends young Miss Faulk, recently hired by Principal Hill. But Principal has designs on this lovely innocent girl and cannot bear the fast, intimate friendship between the two women. Stoked by jealousy and, okay, yes, the occult secrets of his mother, Principal Hill puts a hex on Miss Mack. McDowell writes so well, his quiet evocation of locale and character so confident and matter-of-fact, you won't want the story to end. And in a way it doesn't. The final sickening, maddening horror upends all human notions of time and place, and without those, what are we? Lost in a night that never ends looking for a place that does not exist. When she waked, it was night—still Halloween night. "Miss Mack" has become a favorite of mine from the '80s era.

1988 Severn House hardcover, UK

While enjoyable overall, I do wish Halloween Horrors had a few more tricks to play on readers; many of the stories are slight, mild, unremarkable. Still, a cheap copy is worth searching for, as a couple treats indeed have a razor blade tucked within...

Sunday, November 10, 2013

1983 Horror Fiction Panel Featuring King, Straub, Wagner & More!

An unexpected treat today, thanks to a TMHF Facebook pal who alerted me to its existence just this morning. This is a 50-minute video of a horror fiction panel from 1983 - yes, 1983, 30 years ago exactly - featuring the greats: Stephen King. Peter Straub. Karl Edward Wagner. Charles L. Grant. Dennis Etchison. Chelsea Quinn Yarbro. Whitley Strieber. Alan Ryan. I mean what!

Tuesday, February 26, 2013

The Hunger by Whitley Strieber (1981): Bela Lugosi's Not Dead

Not all that nature wants from its children is innocent.

After the success of his debut horror novel The Wolfen, in which he provided a convincing naturalistic explanation for intelligent werewolf-like predators who've lived side-by-side with humanity throughout the ages, Whitley Strieber reappraised the vampire in the same manner in The Hunger. A mainstream, bestselling thriller with plenty of audience-pleasing sex and violence, The Hunger is also richly veined with concerns about love, relationships, aging and the waning of desire. It follows the arc of history as humanity and its secret vampiric brethren have risen up from the glory of ancient Egypt and the Roman Empire to the mud and muck of the Middle Ages to the brightly-lit but still so dangerous modern era. But for whom is this modern era more dangerous?

Stepback cover, Pocket Books Jan 1982

For whatever reason this novel was made into a glitzy, Gothy, soft-porn movie in 1983, but there is no glitz or Goth here (soft porn, yes). And, smartly I think, the word vampire is never used. Still: there is copious blood-drinking, blood-sharing, blood-shedding, like any self-respecting horror/vampire novel. Then there were moments I felt like Strieber veered into Michael Crichton territory, with renegade scientists researching at the cutting edge of human physiology, making discoveries that will change the world - making the discovery that will change the world. Since Strieber is a powerful and intelligent writer, this concession to bestseller-dom doesn't irritate, since it's presented with the dispassion of a field observer. I rather like a clinical approach to the this kind of material; it makes for an interesting juxtaposition with the hot, unyielding desire for blood.

Don't let his goofball smile fool you...

Miriam Blaylock is an eons old "vampire," a vivid but contradictory character, bold and fearless but endlessly careful in her choosing of victims, terrified of exposing herself to accident and injury which would make her vulnerable to a fate that is, yes, worse than death. The fires of the villagers hundreds of years ago taught her that her kind is not invincible. Her Manhattan home is a veritable fortress battened down with numerous security devices, albeit one that provides beauty and respite, with its luxurious rose garden and old-world furnishings. But Miriam has no relationship with her kith and kin; for centuries she has "enlisted" various specimens of excellent "human stock" to be her companions. And now, she and her current "partner," John Blaylock - 200 years earlier a young British nobleman whose father procured Miriam's illicit services - are growing irrevocably apart.

After epigrams from Keats and Tennyson, the novel opens with a dramatic violent sequence and then reveals that John is unable to "Sleep" (the rejuvenating rest which resembles death) and is aging considerably, woefully, his face in the mirror showing the rack and ruin of years and years, which can only mean he is now facing the end of his unnatural life. Gripped with panic and maddening hunger, his feedings grow more and more careless and desperate as they become less and less satisfying. His rage towards Miriam is growing as he learns there is no escape from a nightmare doom... one for which she alone is responsible.

1981 hardcover

Also introduced in early chapters is Sarah Roberts, a doctor studying sleep and aging and who, after a harrowing tragedy involving her rhesus monkey research subject, seems to have found the link between the two. Her controversial book on the topic has greatly interested Miriam Blaylock. Was it possible for humans to stave off aging utilizing Sarah's discoveries? If so, Miriam could use this knowledge for her own selfish ends when "transitioning" humans via blood transfusion to be her immortal consorts. However, for humans this state of actual immortality is unachievable, as John is so bitterly learning. Sarah's research will indeed mean immortality for humankind. Miriam, longing for eternal companionship, will do anything, even give herself up to scientific research and risk exposure, to convince Sarah to share with her what's she's discovered. And perhaps Sarah - brilliant, lusty, ambitious Sarah - will make the greatest companion of all.

Strieber sketches in Miriam's background with terrific historical passages - ancient Rome, the Dark Ages of Middle Europe, 18th century London - which are economically presented for emotional resonance, adding shades to her and not simply ornamenting the story. It is a life that stretches back to before the Roman Empire; her lineage extends all the way to Lamia herself. These are some of the most enjoyable sequences in The Hunger, so well-conceived and presented as they are. As in The Wolfen, he provides a plausible, ingenious source for the vampire legend. We learn of Miriam's past lovers, that one of her most beloved partners was Eumenes, a youth she rescues after torture by the Roman authorities.

She invented a goddess, Thera, and called herself a priestess. She spun a web of faith and beguiling ritual. They slit the throat of a child and drank the salty wine of sacrifice. She showed him the priceless mosaic of her mother Lamia, and taught him the legends and truths of her people.

Cliched contemporary cover

I've really only touched on what makes The Hunger such a gripping, exciting, illuminating read. Strieber strikes out on a successful path through the psychological intricacies and intimacies that grow between between Miriam and John, between Miriam and Sarah, between Sarah and her fellow scientist and lover Tom Haver, between predator and prey, the seduced and the seducer. There is real darkness here, human darkness and human pain, loss and despair. But also there is the pain of being inhuman, of being, by one's very nature, condemned to exist with a restless intelligence, an insurmountable will to survive, an utterly endless appetite.

Avon Books reprint 1988. No Goth chicks inside however.

And I'm happy to say that as the novel concludes, Strieber ratchets up the stakes with a professional's skill and timing, drawing together the threads of all his characters' disparate stories, till they collide in one ferociously fatal sex scene you gotta read to believe. I mean, that's what we're all waiting for anyway, right? And you get that, and you get much more. This Hunger is one that truly satisfies.

He thought of Sarah and cried aloud. She was in the hands of a monster. It was a simple as that. Perhaps science would never explain such things, perhaps it couldn't.

And yet Miriam was real, living in the real world, right now. Her life mocked the laws of nature, at least as Tom understood them.

Slowly, the first shaft of sunlight spread across the wall. Tom imagined the earth, a little green mote of dust sailing around the sun, lost in the enormous darkness. The universe seemed a cold place indeed, malignant and secret.

Was that the truth of it?

Wednesday, May 4, 2011

Faces of Fear: Encounters with the Creators of Modern Horror, edited by Douglas E. Winter (1985)

Perhaps the most prominent critic of horror fiction during its 1980s reign was Douglas E. Winter. When not lawyering in Washington DC, Winter was interviewing authors, reviewing their books, and even writing his own horror stories, also appearing at horror conventions on writers' panels and generally taking seriously a genre too often plagued by uncaring or condescending mainstream literary critics. He edited several major horror anthologies, but more importantly, he published nonfiction studies of the field, starting with the newsletter Shadowings: A Reader's Guide to Horror Fiction, before moving on to one of the earliest studies of Stephen King, the appropriately-titled The Art of Darkness (1982). Then, Faces of Fear: Encounters with the Creators of Modern Horror.

Perhaps the most prominent critic of horror fiction during its 1980s reign was Douglas E. Winter. When not lawyering in Washington DC, Winter was interviewing authors, reviewing their books, and even writing his own horror stories, also appearing at horror conventions on writers' panels and generally taking seriously a genre too often plagued by uncaring or condescending mainstream literary critics. He edited several major horror anthologies, but more importantly, he published nonfiction studies of the field, starting with the newsletter Shadowings: A Reader's Guide to Horror Fiction, before moving on to one of the earliest studies of Stephen King, the appropriately-titled The Art of Darkness (1982). Then, Faces of Fear: Encounters with the Creators of Modern Horror. Winter handily defended horror fiction against those who saw it as disposable, tasteless, trite, misogynistic, irrelevant. True, lots of horror is exactly that, but Winter knew who had the goods and could deliver unique and powerful work: not only big and expected names like King and Straub and Matheson and Bloch, but also lesser-known writers like Michael McDowell and Dennis Etchison. He was also an early champion of Clive Barker (whose biography he wrote in 2001). And in Faces of Fear, Winter lets these writers, and more, do the talking. In his understated but thoughtful introduction, Winter notes that he avoided questions about various specific works in order to have a more general insight into the writers' private lives. Wisely, the interviewer Winter discreetly disappears so that virtually all we hear are the writers' words themselves.

Winter handily defended horror fiction against those who saw it as disposable, tasteless, trite, misogynistic, irrelevant. True, lots of horror is exactly that, but Winter knew who had the goods and could deliver unique and powerful work: not only big and expected names like King and Straub and Matheson and Bloch, but also lesser-known writers like Michael McDowell and Dennis Etchison. He was also an early champion of Clive Barker (whose biography he wrote in 2001). And in Faces of Fear, Winter lets these writers, and more, do the talking. In his understated but thoughtful introduction, Winter notes that he avoided questions about various specific works in order to have a more general insight into the writers' private lives. Wisely, the interviewer Winter discreetly disappears so that virtually all we hear are the writers' words themselves. Everybody's got some kind of good insight into the writing of horror, as well as the struggle of simply living the writer's life. Some authors discuss their writing habits, or whether or not they're scared by what they write, or if, indeed, they even like being referred to as a horror writer. Things start, appropriately enough, with Robert Bloch (author of Psycho!!!) and his days of correspondence with Lovecraft himself. Detailing his decades of cranking out horror and suspense fiction, he does lament the tendency towards graphic violence in the 1980s, wondering, "What's going to come out of those people who think Night of the Living Dead isn't enough?" (Of course, this was just before the splatterpunks, but I'm sure Bloch couldn't imagine what the kids today are getting up to now with their bizarro fiction.) Then Richard Matheson tries to demythologize the modern reverence towards "The Twilight Zone"; admirable, sure, but definitely unsuccessful. To him, at the time, it was simply a decent writing job.

Everybody's got some kind of good insight into the writing of horror, as well as the struggle of simply living the writer's life. Some authors discuss their writing habits, or whether or not they're scared by what they write, or if, indeed, they even like being referred to as a horror writer. Things start, appropriately enough, with Robert Bloch (author of Psycho!!!) and his days of correspondence with Lovecraft himself. Detailing his decades of cranking out horror and suspense fiction, he does lament the tendency towards graphic violence in the 1980s, wondering, "What's going to come out of those people who think Night of the Living Dead isn't enough?" (Of course, this was just before the splatterpunks, but I'm sure Bloch couldn't imagine what the kids today are getting up to now with their bizarro fiction.) Then Richard Matheson tries to demythologize the modern reverence towards "The Twilight Zone"; admirable, sure, but definitely unsuccessful. To him, at the time, it was simply a decent writing job.Just about all of them reveal that people think they must be somehow warped or disturbed to write horror. After detailing his harrowing experience of nearly being a target of Charles Whitman, Whitley Strieber comes off as a complete crank; I'm surprised his author photo shows him wearing a jaunty fedora and not a tinfoil hat or a crown of oranges. Ramsey Campbell's mother descended into mental illness. Otherwise, these guys are as normal as you or me... take that for what it's worth!

Charles L. Grant's interview takes place in Manhattan's Playboy Club (how's that for dating this book?!); James Herbert talks lovingly about his poverty-stricken upbringing and then jet-setting lifestyle as an ad agency exec before he decided to write novels for a living. The only woman interviewed is not Anne Rice - these interviews were done well before Rice had published her second vampire novel - but the mysterious V.C. Andrews. Um, not my thing whatsoever.

T.E.D. Klein, Dennis Etchison, and Clive Barker have terrifically good things to say about genre writing and the world's perception of it, why pop culture is often savvier about our lives than more so-called respectable pursuits, about horror and why audiences crave it (Klein doesn't even really like the genre, and resigned his post as Twilight Zone magazine editor around this time). Major-leaguers Peter Straub and Stephen King finish up the book with a real flourish in a dual interview. King of course talks of his hatred of being a brand-name, even back then, and reminisces about his days as a college "revolutionary" in the late '60s when he realized he actually did like middle-class life. But I'd say my favorite piece here is about the late Michael McDowell, who unequivocally states his love of being a paperback original writer and how he came to disdain the arid and judgmental nature of the academic literary world. An utterly refreshing attitude!

There is plenty more in Faces of Fear for the real fan of '80s horror fiction: it's a way to see how horror had changed since the pulp era, how it thrived in the paperback boom, and how it even grew up, a little. It's hard to believe the book is a quarter of a century old, but many of the writers are still in print; the ones who aren't are, if this blog and its readers are any evidence, still read and remembered and rediscovered anew.

Labels:

'80s,

berkley books,

clive barker,

douglas winter,

james herbert,

michael mcdowell,

nonfiction,

peter straub,

robert bloch,

stephen king,

t.e.d. klein,

tor books,

whitley strieber

Thursday, April 14, 2011

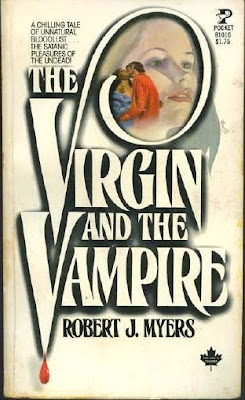

Die, Die, My Darlings: The Lusty Ladies of Paperback Horror

Labels:

'60s,

'70s,

'80s,

anthology,

avon books,

ballantine books,

colin wilson,

george ziel,

gothic horror,

jeff jones,

john shirley,

pocket books,

ray garton,

sexy horror,

theodore sturgeon,

vampires,

whitley strieber

Wednesday, February 9, 2011

Cutting Edge, edited by Dennis Etchison (1986): You Gotta Be Cruel to Be Kind

The 1980s saw plenty of horror anthologies that sought to broaden the scope of the genre, to encourage its growth both as a literary force as well as a mode of delivering fear as entertainment. Horror fans will well recall anthologies like Dark Forces (1980), The Dark Descent (1987), and Prime Evil (1988) as some of the most prominent and well-respected of their day; in 1986, editor Dennis Etchison presented Cutting Edge, which can stand near and perhaps above some of that heralded class.

The 1980s saw plenty of horror anthologies that sought to broaden the scope of the genre, to encourage its growth both as a literary force as well as a mode of delivering fear as entertainment. Horror fans will well recall anthologies like Dark Forces (1980), The Dark Descent (1987), and Prime Evil (1988) as some of the most prominent and well-respected of their day; in 1986, editor Dennis Etchison presented Cutting Edge, which can stand near and perhaps above some of that heralded class. Thoughtful and ambitious horror writers wanted their works to become more real, more penetrating, more relevant, and therefore more terrifying, than ever before and Cutting Edge illustrates that effort. The stories Etchison collected subtly explore very adult concerns and are not much for the supernatural; serial killers and car crashes, drug trips and gender confusion, sexual abuse and Vietnam PTSD wend their way through all the stories. When I first read them as a teenager this approach perplexed me a little, but this reread was much more satisfying.

Thoughtful and ambitious horror writers wanted their works to become more real, more penetrating, more relevant, and therefore more terrifying, than ever before and Cutting Edge illustrates that effort. The stories Etchison collected subtly explore very adult concerns and are not much for the supernatural; serial killers and car crashes, drug trips and gender confusion, sexual abuse and Vietnam PTSD wend their way through all the stories. When I first read them as a teenager this approach perplexed me a little, but this reread was much more satisfying.Etchison's longish yet insightful introduction serves as a shorthand lesson in the failures of genre fiction during the modern era: Tolkien, Heinlein, and Lovecraft impersonators who refused to engage with the fracturing world around them. It's obvious he sees this anthology as "explorations of the inscape," bold new writers unwilling to look backwards, who wish to forge unafraid into untamed territory without regard for genre limitations or, indeed, monetary reward. These stories fall through publication cracks: too raw and intense for the mainstream; not supernatural enough, perhaps, for horror fans bred on "haunted houses and fetid graveyards," as Etchison disparages. He is dead serious; there is none of that obnoxious chumminess that mars so many other anthology introductions. It's this dead seriousness that could seem to be pretension; this may be nearly unavoidable when writers try to class up any genre.

1986 Doubleday hardcover

Just what is "cutting edge"? Besides the obvious reference to mutilation and murder, it's about a style of horror that wants to explore human fear and pain without the typical generic conventions. It can be an experiment in language, as in Richard Christian Matheson's unique "Vampire," a two-page story made up of one-word sentences; it can be the extreme sexual dysfunctions of Karl Edward Wagner's "Lacunae" or Roberta Lannes's "Goodbye, Dark Love"; or it can be the detonated bombscape psyche of Vietnam vets in Peter Straub's excellent, sad, disturbing "Blue Rose" and The Forever War author Joe Haldeman's (pic below) "The Monster." Straub's long story deals with the worst kind of child death and its shattering effect on an already distant and emotionally volatile family and is part of a character cycle that includes his novels Koko (1988), Mystery (1990) and The Throat (1993). His prodigious literary skill is part and parcel of this "cutting edge."

In one of the few stories to use a supernatural creature - Clive Barker's "Lost Souls," with his noir-ish detective Harry D'Amour - the demon is dismissed with a curt "Manhattan's seen worse," meaning, the horrors of a modern world belittle otherworldly chaos, not pale before them. Leave it to old grandmaster Robert Bloch (pic below) to feature the Grim Reaper himself in "Reaper," in which an aging man attempts to deny the final disgrace of death. Classic Bloch, but also fitting in here, in that it confronts a man dismayed by growing old and who'll do anything to miss that last and final appointment.

Lots of us are mixed on Ramsey Campbell but I found "The Hands" to be very good, albeit a bit dense. It's a tense, claustrophobic tale of a man who, after stepping into an old church to get out of the rain, is tricked into "a test of perceptions" by a strange woman with a clipboard, always a sign of officialdom. He's given a pamphlet with the most appalling image of violence he had ever seen. With that vision spinning in his head as well as childhood fears of a vengeful deity, he tries to leave but gets lost in a nameless building and stumbles upon horror.

Drugs and sex figure largely in Wagner's "Lacunae," which is unsurprising, as he often wrote of the dangers of both in a way that spoke of real experience and not just a pose. There's a new drug that fills in the gaps of our conscious minds, all those lost moments finally regained, but perhaps we need those gaps to retain sanity, to keep apart dangerous, contradictory aspects of our most intimate selves. A few years after first appearing in Cutting Edge, "Goodbye, Dark Love" by Lannes was collected in Splatterpunks (1990), and for good reason: it's a short but extremely graphic story of a young woman exorcising the abuse she suffered at the hands of her father. Mixing this kind of psychological insight with unflinching sex and violence was splatterpunk's specialty; hoping for a catharsis instead of just the gross-out. I believe Lannes, and her female protagonist, succeeded.

In both "Lapses" and "The Transfer," by Chelsea Quinn Yarbro and Edward Bryant respectively, women try to deal bravely with random moments in life that open up to unexpected violence and our capacity for both committing and enduring it. There is darkest humor, however, in "They're Coming for You" by Les Daniels and "Muzak for Torso Murderers" by Marc Laidlaw. Other stories, by luminaries such as Charles L. Grant, George Clayton Johnson, and original Playboy associate editor Ray Russell, as well as newcomers like W.H. Pugmire and Nicholas Royle, are all worthwhile.

Steve Rasnic Tem (pictured) contributes "Little Cruelties," one of my favorites, which "excavates" the everyday hurts that we visit upon loved ones. But a father regrets more and more the pain he's caused, and reflects how anonymous cities have almost bred this carelessness inside us. Tem writes strongly and suggestively, with an affectlessness that heightens the prosaic horror.

The final story, "Pain," is Whitley Strieber's mix of tinfoil-hat crankdom - UFOs, the Vril Society, pagan mythology - with a clear-eyed glimpse into the depths of a different kind of S&M. Waxing rather philosophical about death, "Pain" is one of the best stories in Cutting Edge and the perfect end to the anthology, encapsulating as it does all that has come before it. A writer meets a fetching young woman who knows a thing or two about pain:

I wait as she comes scything down the rows of autumn. Although her call will mark the last stroke of my life, it will also say that my suffering is not particular, and in that there is a kindness. She comes not only for me but for those yet unborn, for the old upon their final beds, and the millions from the harvest of war. She comes for me, but also for you, as in the end for us all.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)