"Oh Christ," Bill groaned to himself,

"if this is the stuff grownups have to think about

I never want to grow up."

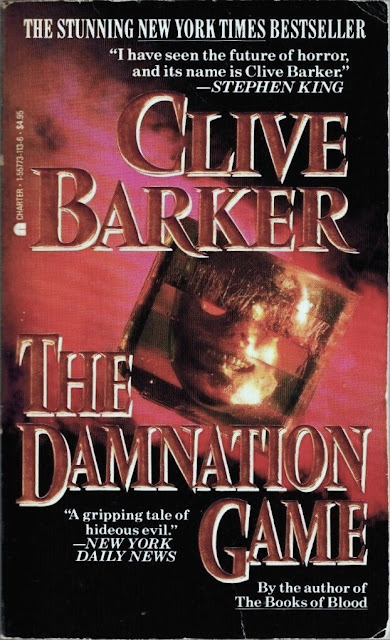

"I am the literary equivalent of a Big Mac and fries,"

Stephen King

famously said back in the Eighties, as a comment on, and perhaps a

defense of, his rising popularity, which was heading right into the

stratosphere. It's a cute, self-deprecating line that defends against

the stuffy critical backlash he often got, and still gets lo these many

decades later. Heading critics off the pass, as it were. But sometimes I

think King undersold himself at times, regular "jes' folks" guy that he

is, and his demotic work often rose above a common fast food meal eaten on the

run. Sometimes it rose above other meals that critics said were much

healthier, more nourishing, for you... but, you know, fuck that.

This is

IT, this is the Eighties horror epic to end all epics, the sum total of Stephen King's career up to that point. King sweeps up all

the detritus, cultural and psychological, of a certain class and

generation of middle Americans, their tastes and desires and fears and

imaginations and jobs and failures, and stuffs them inside a horror

story that is part Fifties monster movie and part mind-expanding cosmic

revelation. As

he said at the time, "Wouldn't it be great to bring on all the monsters one last time? Bring

them all on—Dracula, Frankenstein, Jaws, The Werewolf, The Crawling

Eye, Rodan, It Came from Outer Space, and call it

It."

Look, here there might be a few

spoilers: proceed, if at all, with caution. Come back, friend, when finished with

IT. (Or more precisely, when

IT is finished with

you...)

My wife and I read

IT at the same time late last year, fortunately I had two copies of that Signet paperback from September 1987—what a sturdy little fucker that edition is! She grew up terrified by the famous 1990 TV movie, and therefore was a little reluctant to read it (she's a

Dark Tower acolyte), while I was already out of high school (oh by fall 1990 I was a college sophomore) when that adaptation aired. Me, I was more freaked out by the

'Salem's Lot TV-movie of the late Seventies!

Back in the autumn of 1986, I read

IT as soon as it appeared on bookshelves in hardcover; even sooner, because my librarian mom brought it home for me as soon as the library had received it but before they put it into circulation (a real perk of her job for me, sorry patrons of

Millville Public Library 35 years past—or Millville

Pubic Library, as it was for awhile after a prankster pal of mine swiped the "L" off the sign on the building front, a real Falstaffian wit he was). Fifteen years old and hauling that behemoth into junior high, reading it in study hall, savoring its every terror, is one of my favorite memories of school days.

1st hardcover edition, Viking Press, Bob Giusti cover art

I read through the novel I'm not sure how fast, because it felt like something you wanted to savor. While it's easy to say

IT is, at almost 1,100 pages, self-indulgent, I don't recall ever being bored or frustrated by

IT; while I'd been a reader all my life, by that point my tastes weren't varied at all: King was very much my whole book world, and what he said, went. I don't think I would have even understood that phrase, "self-indulgent," as a criticism. If he wanted to spend 15 pages on, I dunno, a pharmacist and his patient, or half a dozen pages on a town's sewer system, or a man and wife arguing about driving Al Pacino in a limousine, well, dammit, I was gonna read it and be happy!

New English Library, 1987

After my utter disappointment rereading

The Stand ("I need

more about how society collapses" I thought while reading it in January 2020, how's that for irony, har-de-har-har) I almost expected to be just as let down by

IT. But let me make it clear:

IT was an utter satisfying delight to reread. I practically felt

married to it for a few weeks, so thoroughly absorbing as it was. This was, oh so aptly, like visiting an old friend that you thought too many years had passed between you to still have a connection, and then finding out that was not true. My wife and I both were swept up in the propulsive narrative.

Gone was the repetitiveness of

The Stand, gone the bloat, the shallow philosophizing, the social naivete, the tacky characters, the amateurish repetitiveness. There was little self-indulgence to be found. Here, now, was something thoughtful, refined (as refined as King can be, I guess), streamlined (as streamlined as an 1,100-page novel can be, I guess), a smooth-humming vehicle ready to take you to the dark side, all revved up and ready to go.

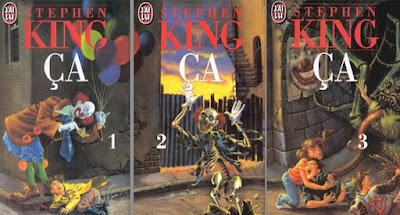

French translation, 1988

It had come here long after the Turtle withdrew into its shell, here to Earth, and It had discovered a depth of imagination here that was almost new, almost of concern. This quality of imagination made the food very rich. Its teeth rent flesh gone stiff with exotic terrors and voluptuous fears: they dreamed of nightbeasts and moving muds; against their will they contemplated endless gulphs.

Online I often see horror fans almost reluctant to read

IT, intimidated by its weightiness. But there's no need to be afraid to tackle this tome: King's prowess in sucking you into the story and enveloping you in his world knows few equals. His storytelling might is in full flower here, and there are few pleasures as welcome as disappearing into a really good read. Rarely did I feel like King was overwriting, or getting bogged down in useless details or wandering off into digressive weeds as he is wont to do. Sure, here and there, he could've pared down a paragraph, a page, a section. But that is to quibble; this shit is pretty tight.

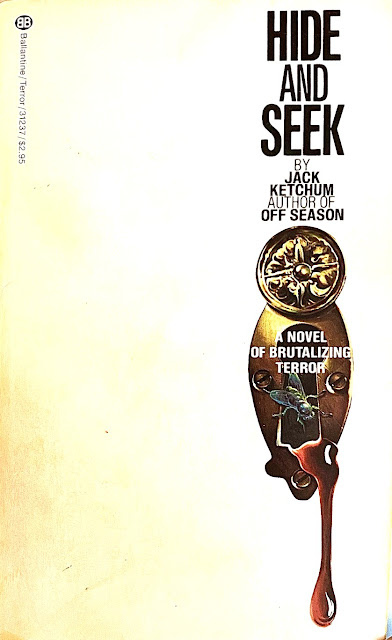

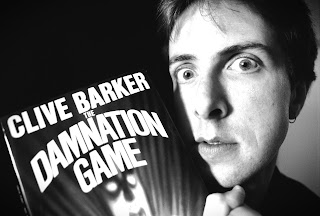

Truth in advertising

I have loved since my first read the Derry Interludes, ostensibly compiled by loyal Mike Hanlon, which are so vivid, so real, so captivating. Found I had forgotten little about them over the years; the eerie chills of Pennywise's infamous appearances throughout Derry's history are some of King's most striking imagery in his catalogue. How I thrill to hear about him capering in the background of a Bonnie-and-Clyde-style ambush, a sad and horrific KKK burning of a Black nightclub, a lumberjack barfight that is more Texas Chainsaw than Texas Roadhouse. The midnight clown prince appears wherever humans wear the mask of evil; he is both its progenitor and its excuse, eager and grinning to join in the fray.

I

had forgotten about how the townspeople of Derry looked the other way, literally, when trouble was afoot, knowing their whole lives that the place they live is tainted, and always has been, in 27-year cycles. In

'Salem's Lot King showed that the town itself is corrupt, and thus drew the vampire to it; here, while Derry is

wrong, it may be because IT has existed inside Derry for millennia, literally buried in its earthen self. The parents of our main characters often seem to look the other way, or who don't quite grasp what's going on with their children: Bill Denbrough's parents are lost in the depth of their grief over the murder of Georgie; Eddie Kaspbrak's mother is delusional about his fragile health; Ben Hanscom's mother takes his attempt at weight loss as a personal affront; Beverly Marsh's father "worries a lot about her." Kids and adults exist, or at least they once did, almost on opposite continents, and King understands this intuitively.

Japanese translation, 1994

I've got to talk about the real-life horrors that populate IT: the homophobic murder of Adrian Mellon in the opening of the Eighties, Tom Rogan's beatings of his wife Beverly Marsh and her friend, the sad lonesome deaths of the abused Corcoran boys, and young sociopath Patrick Hockstetter's animal and sexual cruelty are the scenarios that trouble many contemporary readers—not to mention the tween "love-fest" at the climax (if you'll excuse the pun) of the Losers' tale in the Fifties. As they say now, these situations all hit different today. I recall no particular upset at these occurrences when I first read the book; today, yes, certainly as an adult I'm more sensitive to these depictions that, when used in fiction, can seem exploitative or tone-deaf.

But King is trying to get at real life, and there's no way one can mistake his gut-wrenching depictions for the sleazy, skeevy pulp-horror of so many an Eighties horror writer. These horrific non-supernatural occurrences lend a moral weight to IT that is an essential component; if King had left these disturbing realities out of IT due to some squeamishness, or sense of political correctness, or some idea of "too far," or some notion that certain things cannot be used in fiction, then the book would have been a cheat. And there's nothing worse than a cheat.

Many times on this reread I thought, this book has just as much right to be called

A (not

The, certainly no one book could or should ever be

The)

Great American Novel

as anything else written in the last 50 years or so. The stories of his thirty-something characters after their lives in

Derry come with all the attendant concerns—college, money, sex, career,

ambition, health, aging—well-sketched examples of "how we live now"

school of contemporary fiction. He weaves this tapestry of middle American life into a shared whole, in the guise of genre fiction, to reflect back at us our fears both as children and as adults.

Monsters from Baby Boomer fare like the Teenage Werewolf and the Mummy, midnight clowns and vampires, are something like placeholders; our brains are primed for fear, and those primitive childish creatures build the muscles that we'll use to defend ourselves against the hazards and vicissitudes of life when we're grown. Even ITs final form, the nature-gone-amuck giant-sized

Spider that the adult Losers face in the sewers of Derry, can not be fully comprehended. Not all of us have the stamina—it was right and it was correct for a character like Stan Uris to exist, one person in the troupe utterly unable to face IT again— but those of us who do...

Turkish translation, 1987

Make no mistake: IT contains some of the author's finest frights of his career, none of which are diluted by the book's massive size. King flexes his well-honed horror muscles in memorable scenes large and small, missing no chance to scare the bejabbers out of readers. Chilling, lurid, pulpy, flat-out disgusting—King has mastered every aspect of terror, while knowing that often the most frightening things aren't necessarily a monster on the rampage, but a man who talks to the moon, a child contemplating death, a woman realizing her husband will kill her if he can. King knows how to sneak past your defenses, cut you deep, and then be off before you realize you're bleeding. A balloon, a toy boat, a friendly folk hero, and other icons of childhood can freeze your blood, electrify your spine, make you contemplate gulfs of endless pain in the silvered eyes of a BEEP BEEP RICHIE

"

I'd rather stay here in my room/Nothin' out there but sad and gloom," sings Joey Ramone in the Ramones' snarled-up cover of Tom Waits's creaky dirge "I Don't Want to Grow Up", and you can just see all the Losers nodding in agreement, even if it isn't Little Richard or, god forbid, Pat Boone. It's a nice rebel sentiment, but you won't win any points trying to avoid the inevitable. Adulthood is coming, it is definitely coming. It will have its way with us all, and there surely is intent in Stephen King ending this inevitable journey of losers and winners with that single, all-encompassing, all-meaning word: it.

And oh yeah… my wife loved it too.