Showing posts with label historical horror. Show all posts

Showing posts with label historical horror. Show all posts

Tuesday, September 2, 2025

RIP Chelsea Quinn Yarbro (1942 - 2025)

Prolific, long-time author Chelsea Quinn Yarbro has died at age 82. Known for her historical horror novels about the vampire Count Saint-Germain, Yarbro also wrote excellent short stories and horror movie novelizations. Here is my (unfortunately incomplete) collection of her mass market paperbacks.

Wednesday, February 24, 2021

A Month of Black Sabbaths: The Horror Paperbacks of Daniel Rhodes

Not much to catch the eye in this classy cover art for Next, After Lucifer (July 1988), but the critical blurbs seem to be impressed! One of those authors about whom I never knew anything but whose paperbacks have been plentiful in used bookstores for years, Daniel Rhodes had two more titles published in the late Eighties through Tor's prolific horror line, Adversary and Kiss of Death, from 1989 and 1990 respectively. In the United Kingdom they were put out by New English Library—adorned with much better cover art—complete with Graham Masterton singing the praises.

Looking into the author, turns out Rhodes is a pen name of thriller author Neil McMahon, who is still hard at work today. I was pleasantly surprised to find Next, After Lucifer to be written in a style not usually found in horror paperbacks, elevated and inspired by the stories of M.R. James—the novel is dedicated to the writer—but with requisite updating (drug use, illicit sex). Actually, it was published in hardcover by St. Martin's Press, which might explain the higher quality prose and all-around cultured nature of the tale within.

Anyway, there's an ancient evil in a quaint French town where American medieval studies scholar John McTell and his indifferent newlywed wife Linden are taking a sabbatical. It's Templar Knight Guilhem de Courdeval from the 14th century, burned at the stake for sorcery and various occult antics, whose spirit is trying to invade McTell, thanks to McTell stumbling across the knight's grimoire in castle ruins in the hills. Come on, dude, you're a medieval studies prof, you know waaay better than to mess with that stuff.

Rhodes is a literate and careful writer, and I was impressed by the depiction of local color, an indulgent priest, the villagers, and especially the snobby, drunken antics of Linden's sister, husband, and a Eurotrash hanger-on who crash the McTells' getaway and liven up the proceedings. It's quiet, allusive, historical horror here all the way, which was fine, a couple gory touches, but I definitely felt it lacked a certain je ne sais quoi, or maybe I just mean it needed more oomph in narrative, dramatic tension. Plus there's a sequel I didn't know about, Adversary, so that means the climax is a touch half-hearted. Worth a read, worth adding to your collection, but remember to watch out for grimoires that write themselves...

Thursday, September 17, 2020

Raw Pain Max by Dean Andersson (1988): Nothing's Shocking

One of the most famous literary putdowns of all time is what Truman Capote said of Jack Kerouac's iconic Fifties beat novel On the Road: "That's not writing, that's just typing." Ouch. Reading Raw Pain Max (Pinnacle Books, Oct 1988), that quote came immediately to mind, not least because the two protagonists here are constantly in a car driving hither and yon. Author Dean Andersson, who I have not read before, spends pages and pages padding out a practically

non-existent narrative about torture goddess Countess Bathory in the modern day; his "writing" seems like he's making up his travelogue of terror as he

goes. What we have here, then, is one of those horror paperbacks that sports a gloriously lurid cover, thanks to J.K. Potter, that it can never live up to. The clumsy title, invoking one of Clive Barker's most ferocious tales, helps not at all.

Andersson makes all the mistakes of an inexperienced writer. Filled with non-horror-ific details like

characters' "bad-ass" clothing style of motorcycle boots and rock

t-shirts, heavy metal on the radio, various highway routes from Texas to Kansas, numerous detailed fast food repasts,

and tin-eared dialogue in which the main characters say each

other's names on an endless loop (for me, the A-number-one indicator of an amateur author) Raw Pain grated on my nerves like, well, torture itself. There is no attempt at pacing, plot, suspense, scares, or insight; it is all just so much typing.

Now I don't know anything about Andersson, maybe he's gotten better, but I have

seen his later horror paperbacks around over the years, published in the Eighties

through the Nineties: two Avon paperbacks, 1981 and '82 under the

pseudonym Asa Drake, then Torture Tomb in 1987 and Max the following year, with some Zebra titles later. They pretty succinctly show the variety of horror paperback covers, from historical romance vibe to more generic images like grasping hands and widened eyeballs, then the more photo-realistic style of the Nineties, which you can see at bottom. Love these two Avon covers, totally new to me. Honestly they sound pretty cool, but after reading Raw Pain, man, I dunno.

Back to the task at hand: Raw Pain Max

is about "whip-toting Amazon" Trudy, a twenty-something bodybuilder,

who, along with friends-with-benefits young metalhead Phil, performs a

torture act in a sex club, called, improbably enough, the Safe Sex Club

(look, don't @ me if there is actually a club with that name; it's a

terrible name whether it's a real place or not). On-stage she goes by the

nomme de S&M—wait for it—"Raw Pain Max," or "RPM" for short. Clever. Here, have a taste:

Raw ripped away [Phil's] rip-away clothes, leaving him all but naked in his black sequined G-string. As always the moment of humiliation, even though fake, excited Phil... Raw's whip came down across his stomach. The soft material only barely stung, but he convulsed as if in agony... the music changed to a gear-grinding heavy metal rock number, in response to which RPM removed her cape and began a hip-thrusting, breast-shaking dance around her chained victim... Then she produced a fake knife with a hollow blade that discharged prop blood (washable)... used it to pretend-carve R-P-M on Phil's heaving chest. Crimson dribbles slide down his torso toward his G-string...

Still here? There's a little more:

Raw leaned forward and pantomimed lapping up some of the blood with her tongue... gave the audience a wink, and started to insert the blade beneath Philip's sequins just a moment before the lights went out and the music suddenly stopped. In the silence and darkness, Phil bellowed a long, tortured scream, Raw laughed maniacally, and the act was over.

That wink and maniacal laughter reach across three decades to bring the deep, unsettling cringe. Later, when the Lady Bathory appears, she will also jest and chuckle and grin and do everything else to undercut the gravity of every situation. I find that type of thing—sarcasm, mockery, giggling, laughing evilly—unbearable, utterly unbearable, and it never stops in this book: The Countess chuckled at the jest she had made, then leaned forward, kissed the peasant's mutilated lips, and touched the blood-soaked stitches with the tip of her tongue. "Chuckled." Jesus wept, is this a Bazooka Joe comic.

Ok, ok, and they also make fetish videos for

polyester-clad sleazeball Marv, who runs the joint (yes, he chomps on a

cigar). Phil's backstory is porno-obsessed kid; Trudy's is addict

getting better through health food and weightlifting, and getting in

touch with the darker impulses. This is how Andersson writes their sex

scenes: They got undressed, Phil put on his condom, they made love, and went to sleep. Oof. This is an odd contrast with the hyper-described sex show.

Then Phil's cousin Donna turns up with sleazy girlfriend "Liz" who is pretty obviously Countess Bathory doing some time- and spirit-traveling. Donna's in a weird catatonic state while Liz is an old-school lech, hitting on Trudy right in front of Phil ("Great abs. Great ass. Great everything. Yum"), then later plays mind tricks on them to show her supernatural powers and force them into a deadly sex orgy. Torturing to death a young woman she's brought back to Trudy's home S&M dungeon, Liz then makes all bloody evidence of the horror disappear by the next morning... and the game is afoot! Be ready for all that driving.

The convoluted metaphysics explaining how

Bathory's spirit comes to visit the excessive Eighties seems like they were invented in the moment. Reincarnation? Mind-melding? There are also demonic "pain eaters" lurking in a dream netherworld who have a history of fucking things up royally for everyone, up to and including Christianity. Ironically, the novel's depiction of torture falls flat, amounting to tying victims up with baling wire and sticking fishhooks in their lips, all the while "teasing" punishments that are dead on arrival thanks to Andersson's inexpert approach.

An instant later, the strands of barbed wire began glowing with purple fire, sizzling Trudy's flesh while they also tightening around her breasts, between her legs... "Your breasts will probably be next," Liz told her, "or maybe your head." With a sickening jerk Trudy felt something give way between her legs. Barbed wire ripped upward into her intestines as blood poured down her thighs.

"And just think, darling, this can go on as long as I want. Isn't it just absolutely wonderful?"

This modern-day Countess Bathory sounds more like Sally Bowles than a queen of pain. The culmination of all this blather is scenes of mind-numbing gore, lip-sewing and ball-busting, but nothing an experienced reader hasn't encountered before (I'm considering the book both now and as if I'd read at the time it was first published), and I haven't even mentioned the mind-possession angle. It's all just padded paper depicting juvenile sadism in the most immature, inane manner; there's nothing real or true or honest in Raw Pain. I never felt anyone's pain as I read except for my own.

I can't be the only person to think it's odd that nobody had much utilized Bathory and her crimes in horror fiction up to this point. Ray Russell did it in over 50 years ago in Unholy Trinity; Andrei Codrescu wrote The Bloody Countess as a mainstream thriller in 1995. Andersson was onto something with the basic concept of a reincarnated Bathory, has done his homework, including in the story itself the actual books he used for research, as well as the Eighties metal bands inspired by her misdeeds. Which, you know, great, I too enjoy classic heavy metal and books about history's notorious serial killers. But, as Johnny Thunders and the Heartbreakers once sang, it's not enough.

And how I wanted to enjoy this novel! How I wanted a sleazy, no-holds-barred, bad-taste extravaganza of pain and pleasure, lust and fear, blood and other bodily fluids. Sure, all that stuff is here, but Andersson's penchant for filling up the page with mundane irrelevancies, and amateur execution of actual scenes of horror—or of any kind of real life—negate their presence. Nothing is scary, nothing is sexy, nothing's shocking. Like many a paperback original with a striking cover before and after it, Raw Pain Max over-promises and under-delivers. And so I am reminded of another famous putdown, a paraphrase of Seinfeld's words about his neighbor nemesis Newman: there's not more than meets the eye here—there's less.

Thursday, April 23, 2020

Vampire Junction by S.P. Somtow (1984): The Bloody Days Are Bloody Long

1991 Tor reprint, cover by Joe DeVito

Somtow is the pseudonym of Somtow Papinian Sucharitkul, a Thai-American author who is also a classical music and opera composer, aspects which feature prominently in the novel. These are the most convincing parts of the story, written with obvious first-hand personal knowledge and insight. The retrograde vision of the rock'n'roll industry is taken right from that scene in Rock 'n' Roll High School where the Ramones manager tells Riff Randell "This is the big-time, girly, this is rock 'n' roll." Except played straight and not for midnight movie madness.

1985 Future UK edition, cover by Val Lindahn

Structurally the novel is a mess, flitting back and forth in time not just in chapters but oh-so-preciously separated sections with portentous headings like *blood dream* and *night child* and *firebirth* and even *fire:dissolve:labyrinth* (god is there a more pretentious word than labyrinth?). I admire the ambition, somewhat, the desire to elevate pop fiction nightmares, but this back-and-forth within even paragraphs leaves the reader bewildered.

1990s UK reprint

But what ultimately drags the book down is its insufferable pretension, especially in the last quarter building to the fiery, ludicrously sexual, er, climax. This high-mindedness is mixed with foul-mouthed vampire hunters, an inexpert mingling of the sacred and the profane that produces a jarring effect. It's exhausting to read. Despite a few cool scenes of vampire grue and black-humored satire of pop music, Vampire Junction is a stop you can skip.

Friday, February 23, 2018

The Flesh Eaters by L.A. Morse (1979): Eat 'Em and Smile

Behold the Frazetta glory that adorns this paperback! Inhuman brutes, their flesh gone grey-green from their ghastly diet (yet somehow they're ripped as hell), drag along another hapless victim to their lair hidden by great rocks in a misty, nightmarish landscape—what self-respecting horror fan could resist reading this book? Why it promises terrors beyond imagining! Slim, grim, and altogether grimy, The Flesh Eaters (Warner Books, Dec 1979), an unheralded vintage title by one L.A. Morse, operates in that unwholesome arena of dead-eyed depiction of graphic, taboo-obliterating violence with not a whiff of concern for taste or restraint. As you'll see, this is an altogether good thing.

This story of legendary Sawney Beane and his unholy clan is a master class in unsettling the unwary reader. Me, I had some idea of what I was getting into, but even so I was somewhat astonished—and impressed—at the darker turns the narrative took. A straightforward tale of supposedly historical events: a preface declares the factual (meh) basis of the novel, and Morse spares no ugly detail in describing the sheer shittiness of life in 15th-century Edinburgh. There are the houses basically made of mud and straw, the miasma of garbage and human waste, the scavenging creatures animal and man alike, the cathedral filled with light and wealth. The townspeople have no experience of any alternatives. If a clean town does not exist for them, then this town is not dirty.... This filth is merely one of the necessary accompaniments of progress.

Two kids have killed the father, now they've gotta be on the run. That they do. Before, Sawney Beane was practically mute, a cipher, a dullard, a nothing, barely existing, barely thinking, barely feeling. Post-murder he is in touch with desires and sensations that before had only moved about him like beckoning shadows. Oh he has solved the sweet mystery of life, Sawney Beane has! He explains to Meg as they leave that dirty old town:

Well all right! Now we're talkin'. The two self-imposed exiles trudge through spooky forest and across lonely beach and lo and behold, Sawney finds a tiny crevasse in a cliff face which he explores, finding that it turns into a dry, lofty cavern: the perfect home for he and his carnal bride, virtually invisible to any human eye. Here will be their hearth from which they will venture only to kill unsuspecting travelers on the road above. What follows are simple, sometimes gut-wrenching depictions of remorseless killers at work and the enjoyment they find in overpowering the weak things. To wit:

Then the inevitable occurs: Meg becomes pregnant. The baby's birth makes Sawney squeamish; he can't watch and he certainly can't cut the umbilical cord! Even looking at this mewling creature is beyond him... till he realizes: their numbers can increase. So will their strength. And so then will the fear they can cause in the others. Our numbers will increase.... We have only begun.

Once the Beanes start to procreate, things get sketch as eff. Meg gives birth yearly. The children have no names but their jaws are strong. They function almost as one organism, moving and breathing in harmony. The children know no life other than that of the cave; they accept it as normal. Sawney rules as patriarch, of course, teaching his loathsome offspring that "the things are stupid.... It is very funny when they know they are dead." To his clan he spins a myth of the grey wolf of the forest, a tale he remembers from his hazy youth: the wolf is both his own father and he, the supreme predator of the dark woods. The children lie in wait in lonely roads, one pretending to be injured, perhaps, to lure the unsuspecting travelers to aid; then father pounces. The eldest son wants dearly to be a hunter like his father, and the younger children want to partake in the kills on their own. Sawney is not sure if they're ready... but he is willing to let them try.

(Maybe skip this section if you want to experience the book for yourself) If you thought murder and cannibalism were the deepest depravities Flesh Eaters was going to plumb then you've thought wrong. There is rape and incest, and, in one dizzying moment of pure outsider horror, Morse notes the undercurrent of sexuality in the family... sexual energy crackles through the cave; the smell of lust is heavy. Like a pack of wild dogs, the family couples at every opportunity. All but the youngest children are involved, and these imitate their elders, pressing their naked loins together, thrusting their hips in a parody of the sexual act. Holy Jeezus.

They exist apart from human notions of morality or value; again and again Morse notes the uselessness of money and clothes and other "booty" accrued from their victims. "It's shit," Sawney Beane says more than once, tossing away gold coins and fine clothing, "all that belongs to them is shit. This is why they are weak." Morse crafts these scenarios for maximum impact with minimum stylized force: he doesn't overwrite or oversell his disturbing visions; his plain, unadorned prose simply documents horrific events but does not comment on them. Victims rarely have identity; those that do serve a larger purpose to the plot.

There is more to the novel than these grotesqueries of appetite and destruction: the townspeople hear of more and more traveler disappearances (the story takes place over two decades). Their idiot Sheriff is lazy, not very smart except when it comes to avoiding difficulties, cowardly, and inordinately fond of his own voice. Perhaps it is a demon responsible? A priest is called. No luck. Several innocent men are accused of devil worship and human sacrifice after a rotted arm is found washed ashore; the men are tortured to confess and executed (the classic "throw the accused in the water, if he drowns he is innocent" is employed to sad effect). Morse gets good mileage out of dry political satire in these instances. Finally the King is involved, a search party started, and the noose begins to tighten around the Sawney Beane clan.

This brief work—just over 200 pages—has power and pull; you'll read it quick as Morse goes straight for the jugular with his clean prose shaved to the bone (he was also the author of several hard-boiled crime novels and won an Edgar Award). Don't let that Frazetta cover fool you: this is no tale of dark fantasy or thrilling adventure; it is all too prosaically real. Like Jack Ketchum, whose own landmark work of stark yet extreme horror Off Season (1981) was almost surely inspired by this novel, Morse notes depravity with clarity but does not linger or cheapen. Flesh Eaters is perhaps not a book for every horror fan, but it is a must for every horror fan who likes horror fiction nasty, brutish, and short. Get your hands on this book, devour and enjoy.

This story of legendary Sawney Beane and his unholy clan is a master class in unsettling the unwary reader. Me, I had some idea of what I was getting into, but even so I was somewhat astonished—and impressed—at the darker turns the narrative took. A straightforward tale of supposedly historical events: a preface declares the factual (meh) basis of the novel, and Morse spares no ugly detail in describing the sheer shittiness of life in 15th-century Edinburgh. There are the houses basically made of mud and straw, the miasma of garbage and human waste, the scavenging creatures animal and man alike, the cathedral filled with light and wealth. The townspeople have no experience of any alternatives. If a clean town does not exist for them, then this town is not dirty.... This filth is merely one of the necessary accompaniments of progress.

We're introduced to Sawney and the other townspeople as they're watching the merciless executions of several prisoners, a momentous event that breaks the monotony of daily life. Of course after watching the men killed in vile ways he feels a tingling throughout his body, a pleasant warmth in his groin. He even sniffs blood from the ground and totally gets off on it. Then it's off to work in the blacksmith's, a horrible abusive guy, known as Master, but he's got this hot teenage daughter, Meg, who hates being her father's slave. Meg and Sawney develop I guess a "relationship." One night the blacksmith is drinking with a pal, and they humiliate Sawney and grope Meg. After being rejected by Meg, the pal leaves, and the blacksmith then attempts to rape his own daughter—till Sawney steps in to stop him. You can guess what happens:

At last Sawney Beane and Meg become exhausted and stop. There is blood all over them. Sawney Beane puts his hand in a wound on the Master's chest and brings it out covered with blood. He licks his hand, then holds it in front of Meg's face. She licks one finger slowly with the tip of her tongue; and then takes each of the other fingers into her mouth and sucks them greedily. Her lips are swollen, as though with passion.

They begin to laugh maniacally.

ebook cover 2014

Two kids have killed the father, now they've gotta be on the run. That they do. Before, Sawney Beane was practically mute, a cipher, a dullard, a nothing, barely existing, barely thinking, barely feeling. Post-murder he is in touch with desires and sensations that before had only moved about him like beckoning shadows. Oh he has solved the sweet mystery of life, Sawney Beane has! He explains to Meg as they leave that dirty old town:

"We will become hunters. We will be like the great wolves of the forest. Only we will not attack cows and sheep and deer. We will hunt men... Aye, eat them! Feed upon them..."

Well all right! Now we're talkin'. The two self-imposed exiles trudge through spooky forest and across lonely beach and lo and behold, Sawney finds a tiny crevasse in a cliff face which he explores, finding that it turns into a dry, lofty cavern: the perfect home for he and his carnal bride, virtually invisible to any human eye. Here will be their hearth from which they will venture only to kill unsuspecting travelers on the road above. What follows are simple, sometimes gut-wrenching depictions of remorseless killers at work and the enjoyment they find in overpowering the weak things. To wit:

They are the hunters and it is natural to hunt; anything else would be unnatural. Eating the flesh of their victims no longer has special significance. It is natural for hunters to eat what they kill. They feel no connection between themselves and their victims, no common humanity... they stand over their fallen victims, yelling at the corpses, cursing them, kicking them, spitting on them, dancing in triumph over their bodies

Then the inevitable occurs: Meg becomes pregnant. The baby's birth makes Sawney squeamish; he can't watch and he certainly can't cut the umbilical cord! Even looking at this mewling creature is beyond him... till he realizes: their numbers can increase. So will their strength. And so then will the fear they can cause in the others. Our numbers will increase.... We have only begun.

Once the Beanes start to procreate, things get sketch as eff. Meg gives birth yearly. The children have no names but their jaws are strong. They function almost as one organism, moving and breathing in harmony. The children know no life other than that of the cave; they accept it as normal. Sawney rules as patriarch, of course, teaching his loathsome offspring that "the things are stupid.... It is very funny when they know they are dead." To his clan he spins a myth of the grey wolf of the forest, a tale he remembers from his hazy youth: the wolf is both his own father and he, the supreme predator of the dark woods. The children lie in wait in lonely roads, one pretending to be injured, perhaps, to lure the unsuspecting travelers to aid; then father pounces. The eldest son wants dearly to be a hunter like his father, and the younger children want to partake in the kills on their own. Sawney is not sure if they're ready... but he is willing to let them try.

(Maybe skip this section if you want to experience the book for yourself) If you thought murder and cannibalism were the deepest depravities Flesh Eaters was going to plumb then you've thought wrong. There is rape and incest, and, in one dizzying moment of pure outsider horror, Morse notes the undercurrent of sexuality in the family... sexual energy crackles through the cave; the smell of lust is heavy. Like a pack of wild dogs, the family couples at every opportunity. All but the youngest children are involved, and these imitate their elders, pressing their naked loins together, thrusting their hips in a parody of the sexual act. Holy Jeezus.

They exist apart from human notions of morality or value; again and again Morse notes the uselessness of money and clothes and other "booty" accrued from their victims. "It's shit," Sawney Beane says more than once, tossing away gold coins and fine clothing, "all that belongs to them is shit. This is why they are weak." Morse crafts these scenarios for maximum impact with minimum stylized force: he doesn't overwrite or oversell his disturbing visions; his plain, unadorned prose simply documents horrific events but does not comment on them. Victims rarely have identity; those that do serve a larger purpose to the plot.

The only image of author Morse found

This brief work—just over 200 pages—has power and pull; you'll read it quick as Morse goes straight for the jugular with his clean prose shaved to the bone (he was also the author of several hard-boiled crime novels and won an Edgar Award). Don't let that Frazetta cover fool you: this is no tale of dark fantasy or thrilling adventure; it is all too prosaically real. Like Jack Ketchum, whose own landmark work of stark yet extreme horror Off Season (1981) was almost surely inspired by this novel, Morse notes depravity with clarity but does not linger or cheapen. Flesh Eaters is perhaps not a book for every horror fan, but it is a must for every horror fan who likes horror fiction nasty, brutish, and short. Get your hands on this book, devour and enjoy.

Tuesday, January 10, 2017

Yellow Fog by Les Daniels (1988): Blood and Tears

Now here's a Stephen King paperback blurb you can believe! Author Les Daniels (1943-2011) had been writing his series of historical vampire novels for about a decade, all featuring the "protagonist" Don Sebastian Villanueva, an immortal Spanish nobleman. Yellow Fog (Tor Books, August 1988/cover by Maren) was originally published in 1986 by specialty genre publisher Donald M. Grant (see cover below) and is the second-to-last in the series. The only other novel of his I've read is the last one, No Blood Spilled (1991), which I quite enjoyed. In fact I wished Daniels had written more of these! Daniels has lively way with common classic monster tropes, delivered in the fond, knowing manner of someone well-acquainted with them. Yellow Fog is highly reminiscent of Charles Grant's Universal Monsters series (also published by Donald M. Grant) but surpasses that because Daniels is a much, much livelier writer, engaging the reader with effortlessly-drawn characters and setting.

To begin: after an intense train crash prologue in 1835 that leaves one survivor, we move forward to 1847 and meet twenty-ish Londoner Reginald Callender, a callow, immature, shallow, and greedy fellow. Rather than being a unlikable protagonist, Reggie (how he hates that diminutive!) provides much delight for the reader as he is repeatedly confounded in his efforts to secure vast wealth at his own minimum cost. His rich uncle William Callender, he of upper-crust London country clubs, of wealth and taste and hidden vice, has shuffled off this mortal coil, which doesn't upset Reginald overmuch as he stands to inherit the old man's hard-earned money. And yet that is not to be. Even though betrothed to the lovely Felicia Marsh, a young woman with her own inheritance—and the survivor of that earlier train crash— Reginald is beside himself with frustrated greed when he learns Uncle W. left behind nothing save enough to cover his (extensive) funerary, legal, and my-mistresses-shall-be-cared-for-after-I'm-gone costs.

Felicia, as well as her middle-aged Aunt Penelope, are intrigued by all manner of the occult, superstition, and questions of life after death. "Death is only a passage," Felicia tells a nonplussed Callender after his uncle dies, "A journey to another land." She speaks of a man named Newcastle, who can communicate with spirits, and invites Callender along with her and Auntie to one of his seances. Grumbling at the indignity of a betrothed who believes such nonsense, Callender goes along. He's taken aback by this Sebastian Newcastle: clad in black, drooping black mustache on a scarred white face, inviting them into his darkened home lit only by candlelight. The creepy seance that follows, in which Uncle W., in all his irascibility, appears, does nothing to convince Callender that Newcastle isn't a fraud after Felicia's inheritance. Neither does Callender realize that Newcastle is, the astute reader will have noticed, a real live vampire.

Callender, suspicious as only a crook can be, hires a former "runner," a kind of private detective, named Samuel Sayer, to look into the elusive Newcastle. Callender learns of Sayer through Sally Wood, a nightclub singer and dancer, a woman of "cheerful disarray" who would not do as a wife but does great as a mistress (but of course) and who is fond of a new work of fiction titled Varney the Vampyre ("Sounds deucedly unpleasant to me," he sniffs). A wonderful scene ensues of Callender tracking Sayer down at The Black Dog, a dingy bar of ill repute, and later Sayer explains who, and what, he is, and what he does and how. It's a great bit of political theater, a hard-bitten old gent explaining things to a clueless snob.

A visit to Madame Tussaud's House of Horrors thrills and chills Aunt Penelope and Felicia as they are accompanied there by Mr. Newcastle, Callender muttering behind the latter two as they view torture instruments and waxen murderers. Then out steps aged Mme. Tussaud herself, who takes one look at Newcastle and states, "Have we not met, sir?... There were stories in Paris, when the revolution raged, about a magician, one who had found a way to keep himself alive forever." Newcastle, polite and deferential as all get-out, engages her in an ironic conversation that Callender can barely stand. The nerve of this guy! Sayer really better be worth it, he's thinking. Of course you can probably guess what happens to Sayer, and to Felicia as she's drawn under Newcastle's spell. Or is she? Perhaps she goes willingly, to see the other side...

Of course you may be able to guess what happens a lot of the time. That's rather the enjoyment factor in Daniels's work. He doesn't belabor readers with details they can fill in themselves: the stinking fog-enshrouded cobblestone streets of early 19th century London; a dank, frigid dock on the Thames; a derelict bar; the Gothic horror/romance of a church graveyard haunted by the shades of the dead; the candlelit drawing room during a seance. Sketched briefly, these settings are perfect for the characters that inhabit them. Sharp dialogue and keenly-observed human folly Daniels does quite well, and his knack for plot, short chapters that clearly advance the narrative, are quite welcome; moments of dramatic confrontation are scattered throughout the book, satisfying hooks of grue that propel readers forward. Daniels could have in my opinion been quite a scriptwriter.

Weaving interesting historical trivia into an larger story to add color and background isn't always easy; it can read too much like an encyclopedia entry. Daniels knows, and does, better. In Yellow Fog, readers will learn a bit about the origins of England's professional police force, the class distinctions relevant to it, and find it all fits with the larger tale of vampirism, greed, and desire (Daniels shrewdly compares Callender's incipient alcoholism to the vampire's bloodthirst). I read the novel over two cold, rainy days, listening to John Williams's score for the 1979 Dracula, and I consider it time well-spent.

Early on the notion struck me that, considering the familiar scenario, that Yellow Fog was a cozy-horror. Unlike the cozy-mystery, there is violence, and sex, fairly explicit, but in such a way that is easily digestible; Daniels is not upending decades of horror convention, he is simply utilizing them in a satisfying, understanding manner. You know what you're getting, you get it, maybe a little bit extra, but it's all been seen before... which is precisely the point. Sayer's meeting with Newcastle, Callender meeting Sally at novel's end: both provide the serious horror creeps. The finale sets up No Blood Spilled, I guess at some point I'm gonna go back and read the previous installments, see what I missed.

This is horror comfort food, if you will. When you want mom's mashed potatoes, or grandma's mac n' cheese, nothing else will do; when you want a Universal or Hammer-style vampire story, that's what you want and no revisionist take will do. Okay, there's some Anne Rice-style eroticism tinged with immortal regret, but you had that first in Universal Dracula's Daughter way back in '36. Daniels knows what's up.

To begin: after an intense train crash prologue in 1835 that leaves one survivor, we move forward to 1847 and meet twenty-ish Londoner Reginald Callender, a callow, immature, shallow, and greedy fellow. Rather than being a unlikable protagonist, Reggie (how he hates that diminutive!) provides much delight for the reader as he is repeatedly confounded in his efforts to secure vast wealth at his own minimum cost. His rich uncle William Callender, he of upper-crust London country clubs, of wealth and taste and hidden vice, has shuffled off this mortal coil, which doesn't upset Reginald overmuch as he stands to inherit the old man's hard-earned money. And yet that is not to be. Even though betrothed to the lovely Felicia Marsh, a young woman with her own inheritance—and the survivor of that earlier train crash— Reginald is beside himself with frustrated greed when he learns Uncle W. left behind nothing save enough to cover his (extensive) funerary, legal, and my-mistresses-shall-be-cared-for-after-I'm-gone costs.

Felicia, as well as her middle-aged Aunt Penelope, are intrigued by all manner of the occult, superstition, and questions of life after death. "Death is only a passage," Felicia tells a nonplussed Callender after his uncle dies, "A journey to another land." She speaks of a man named Newcastle, who can communicate with spirits, and invites Callender along with her and Auntie to one of his seances. Grumbling at the indignity of a betrothed who believes such nonsense, Callender goes along. He's taken aback by this Sebastian Newcastle: clad in black, drooping black mustache on a scarred white face, inviting them into his darkened home lit only by candlelight. The creepy seance that follows, in which Uncle W., in all his irascibility, appears, does nothing to convince Callender that Newcastle isn't a fraud after Felicia's inheritance. Neither does Callender realize that Newcastle is, the astute reader will have noticed, a real live vampire.

Callender, suspicious as only a crook can be, hires a former "runner," a kind of private detective, named Samuel Sayer, to look into the elusive Newcastle. Callender learns of Sayer through Sally Wood, a nightclub singer and dancer, a woman of "cheerful disarray" who would not do as a wife but does great as a mistress (but of course) and who is fond of a new work of fiction titled Varney the Vampyre ("Sounds deucedly unpleasant to me," he sniffs). A wonderful scene ensues of Callender tracking Sayer down at The Black Dog, a dingy bar of ill repute, and later Sayer explains who, and what, he is, and what he does and how. It's a great bit of political theater, a hard-bitten old gent explaining things to a clueless snob.

"A pup like you has no idea what London was like before there was such a thing as a Bow Street runner. Nobody to enforce the law at all... [the runners were] men who were as sly and strong and ruthless as the thieves and murderers they were hired to catch. And I was one of 'em!"

Donald M. Grant hardcover, 1986, art by Frank Villano

A visit to Madame Tussaud's House of Horrors thrills and chills Aunt Penelope and Felicia as they are accompanied there by Mr. Newcastle, Callender muttering behind the latter two as they view torture instruments and waxen murderers. Then out steps aged Mme. Tussaud herself, who takes one look at Newcastle and states, "Have we not met, sir?... There were stories in Paris, when the revolution raged, about a magician, one who had found a way to keep himself alive forever." Newcastle, polite and deferential as all get-out, engages her in an ironic conversation that Callender can barely stand. The nerve of this guy! Sayer really better be worth it, he's thinking. Of course you can probably guess what happens to Sayer, and to Felicia as she's drawn under Newcastle's spell. Or is she? Perhaps she goes willingly, to see the other side...

Of course you may be able to guess what happens a lot of the time. That's rather the enjoyment factor in Daniels's work. He doesn't belabor readers with details they can fill in themselves: the stinking fog-enshrouded cobblestone streets of early 19th century London; a dank, frigid dock on the Thames; a derelict bar; the Gothic horror/romance of a church graveyard haunted by the shades of the dead; the candlelit drawing room during a seance. Sketched briefly, these settings are perfect for the characters that inhabit them. Sharp dialogue and keenly-observed human folly Daniels does quite well, and his knack for plot, short chapters that clearly advance the narrative, are quite welcome; moments of dramatic confrontation are scattered throughout the book, satisfying hooks of grue that propel readers forward. Daniels could have in my opinion been quite a scriptwriter.

Raven UK paperback 1995, art by Les Edwards

Weaving interesting historical trivia into an larger story to add color and background isn't always easy; it can read too much like an encyclopedia entry. Daniels knows, and does, better. In Yellow Fog, readers will learn a bit about the origins of England's professional police force, the class distinctions relevant to it, and find it all fits with the larger tale of vampirism, greed, and desire (Daniels shrewdly compares Callender's incipient alcoholism to the vampire's bloodthirst). I read the novel over two cold, rainy days, listening to John Williams's score for the 1979 Dracula, and I consider it time well-spent.

Origins of cover art: Germán Robles in El Vampiro (1957)

This is horror comfort food, if you will. When you want mom's mashed potatoes, or grandma's mac n' cheese, nothing else will do; when you want a Universal or Hammer-style vampire story, that's what you want and no revisionist take will do. Okay, there's some Anne Rice-style eroticism tinged with immortal regret, but you had that first in Universal Dracula's Daughter way back in '36. Daniels knows what's up.

Then they were on the carpet, her carefully coiffed pale hair spilled upon its darkness, her gown in disarray, her body throbbing with delight and dread. She felt an ecstasy of fear, stunned more by the desires of her flesh than by the small, sweet sting she felt as he sank into her and life flowed between them... She took life and love and death and made them one...

She was at peace, but Sebastian knew that she would rise full of dark desire when the next sun set.

His tears, when they came, were tinged with her bright blood.

Wednesday, June 22, 2016

Ammie, Come Home by Barbara Michaels (1968): That Ghastly Thing in the Parlor

It may not surprise you when I say I only read Ammie, Come Home because I really dug the cover art for this 1969 Fawcett Crest paperback. The eerie landscape and the floating girl, her barefoot vulnerability and that blackening sky beyond, really struck me in a positive way, even though 1960s Gothic novels are not my thing. Venerable paperback artist Harry Bennett hooked me into reading a novel I never would have otherwise! Well-done, sir.

Barbara Michaels is one of the pseudonyms of Barbara Mertz (1927 - 2013), a prolific writer and Egyptologist; her most famous nom de plume was Elizabeth Peters, under which she wrote like endless dozens of mysteries I remember from my old used bookstore days. Ammie is a pleasant enough read, nothing earth-shattering, perhaps even too mild for some contemporary readers. Here and there a jagged edge appears, a moment or a scene of black dread and emotional distress, a slow build-up of the supernatural; the evil deeds of the past wending their way through history only to end up at the tag-end of the groovy generation-gapped 1960s!

Ruth Bennett, widowed, mid-40s, lives in a stately Georgetown, Washington DC home built in the 1800s, inherited from an elderly aunt. Her college-aged niece Sara is boarding with her while attending a nearby school; the novel begins with Sara introducing her aunt Ruth to Professor Pat MacDougal. Big, blunt, brilliant, Ruth isn't sure she likes him. Right off the bat I'm a little iffy on this set-up because it's the stuff of romance novels, in which the two foreordained lovers hate each other on sight... until they don't. It's a generic convention I personally can't abide. Fortunately Michaels doesn't dwell on it overmuch. Prof has a tendency to bloviate and condescend, no surprise, but will prove a formidable foe in the soon-to-come battle against otherworldly forces. Also along is young Bruce, one of Sara's friends, a not-really-boyfriend who today would probably bitch and moan about his being friend-zoned. He's kind of a hipster doofus too, but like the Prof, he really steps up when strange things are afoot.

A black smoky shadow appears in a dream of Ruth's one night, but, as one other unlucky lady once put it, "This is no dream, this is really happening!" She hears someone calling "Come home, Sammie" and thinks maybe a neighbor is looking for their cat. This event is set aside as MacDougal invites Ruth to his mother's home for a society soirée, the main event of which is, can you dig it, a séance. Ruth thinks it's a scam, this medium Madame Nada conjuring up long-dead folks from the Revolutionary War (still kind of a big deal in tony Washingtonian circles). What's funny in a modern problems way is that Ruth invites both Mac's mom and the medium to a dinner party in her own home! Motivated more by social duty than true warm-heartedness, this dinner party turns into one bizarre affair. No good deed, etc.

After a discussion on the paranormal between Bruce (he accepts it), Mac (he doesn't), and Ruth (she's unsure), Mac parses Ruth well: "You are fastidious," he tells her. "You dislike the whole idea, not because it's irrational but because it's distasteful." Oh snap! The author will well note the strain supernatural occurrences put on daily living; it's difficult to keep up appearances when one's niece is suddenly a conduit to a crime committed in one's own house two hundred years earlier. Bruce endeavors in good faith to plumb the mystery, researching Ruth's home in town archives while Mac argues from the viewpoint of scientific rationality. Poor Sara, when not being possessed, kind of lounges about in a miniskirt, getting disapproving looks from her aunt and opposite ones from the Prof (ew!). Every now and again she'll pop in with a stray observation (it's not Sammie, it's Ammie!) but otherwise she's only a pawn in the possession game. Unspoiled, modern, guileless; she's around but not all there, I suppose, a vessel for the plot but not in and of herself; how could she have character if she is unsullied?

Experienced travelers in the realm of horror/supernatural/occult fictions will recognize familiar notes in the story. I find this rather comforting. I appreciated the author's efforts at detailing the banal everydayness that co-exists with the crazy: food, traffic, clothing, cleaning. The turbulent 1960s are noted here and there as Ruth is ambivalent about Bruce and his college-bred revolutionary airs and his designs on Sara. Ammie is also, as many of these pop novels are, charmingly dated: endless miniskirts, dudes with long hair, Ruth's old-lady attitudes (she's only in her 40s! She's never eaten pizza!), Bruce's hip-academic pretensions. Sometimes this aspect is less charming: gender normativity/misogyny out the wahoo in Prof's not-so-subtle lechery, and the time Bruce declares there are "women you rape and women you marry." Yee-ow.

As the origins of the possession become clearer, our narrative becomes tauter: Bruce learns more about the home and its literal foundations ("the whole house is rotten with hate"). A friendly Father figure is enlisted to aid in an exorcism and this goes poorly. Then the old Prof isn't so above-it-all as he'd like to appear; is he part of what seems to be a historical reenactment from beyond? The back-story is satisfyingly unsettling; you'll agree it's a crime that deserves retribution through the ages. Ammie, Come Home ends on a note of sentiment, but it is only the beginning in a three-book series that Michaels continued into the 1990s. I found the novel to be decidedly okay and won't be reading the rest; go ahead and check it out if you think you'll dig a quaint snapshot of the supernatural '60s and a helluva generation gap.

Postscript: for two other takes on the novel, check out Dark Chateaux and The Midnight Room. And thanks for the pix guys!

Barbara Michaels is one of the pseudonyms of Barbara Mertz (1927 - 2013), a prolific writer and Egyptologist; her most famous nom de plume was Elizabeth Peters, under which she wrote like endless dozens of mysteries I remember from my old used bookstore days. Ammie is a pleasant enough read, nothing earth-shattering, perhaps even too mild for some contemporary readers. Here and there a jagged edge appears, a moment or a scene of black dread and emotional distress, a slow build-up of the supernatural; the evil deeds of the past wending their way through history only to end up at the tag-end of the groovy generation-gapped 1960s!

Ruth Bennett, widowed, mid-40s, lives in a stately Georgetown, Washington DC home built in the 1800s, inherited from an elderly aunt. Her college-aged niece Sara is boarding with her while attending a nearby school; the novel begins with Sara introducing her aunt Ruth to Professor Pat MacDougal. Big, blunt, brilliant, Ruth isn't sure she likes him. Right off the bat I'm a little iffy on this set-up because it's the stuff of romance novels, in which the two foreordained lovers hate each other on sight... until they don't. It's a generic convention I personally can't abide. Fortunately Michaels doesn't dwell on it overmuch. Prof has a tendency to bloviate and condescend, no surprise, but will prove a formidable foe in the soon-to-come battle against otherworldly forces. Also along is young Bruce, one of Sara's friends, a not-really-boyfriend who today would probably bitch and moan about his being friend-zoned. He's kind of a hipster doofus too, but like the Prof, he really steps up when strange things are afoot.

A black smoky shadow appears in a dream of Ruth's one night, but, as one other unlucky lady once put it, "This is no dream, this is really happening!" She hears someone calling "Come home, Sammie" and thinks maybe a neighbor is looking for their cat. This event is set aside as MacDougal invites Ruth to his mother's home for a society soirée, the main event of which is, can you dig it, a séance. Ruth thinks it's a scam, this medium Madame Nada conjuring up long-dead folks from the Revolutionary War (still kind of a big deal in tony Washingtonian circles). What's funny in a modern problems way is that Ruth invites both Mac's mom and the medium to a dinner party in her own home! Motivated more by social duty than true warm-heartedness, this dinner party turns into one bizarre affair. No good deed, etc.

Meredith Press hardcover, 1968

After a discussion on the paranormal between Bruce (he accepts it), Mac (he doesn't), and Ruth (she's unsure), Mac parses Ruth well: "You are fastidious," he tells her. "You dislike the whole idea, not because it's irrational but because it's distasteful." Oh snap! The author will well note the strain supernatural occurrences put on daily living; it's difficult to keep up appearances when one's niece is suddenly a conduit to a crime committed in one's own house two hundred years earlier. Bruce endeavors in good faith to plumb the mystery, researching Ruth's home in town archives while Mac argues from the viewpoint of scientific rationality. Poor Sara, when not being possessed, kind of lounges about in a miniskirt, getting disapproving looks from her aunt and opposite ones from the Prof (ew!). Every now and again she'll pop in with a stray observation (it's not Sammie, it's Ammie!) but otherwise she's only a pawn in the possession game. Unspoiled, modern, guileless; she's around but not all there, I suppose, a vessel for the plot but not in and of herself; how could she have character if she is unsullied?

Uber-lame reprints

Experienced travelers in the realm of horror/supernatural/occult fictions will recognize familiar notes in the story. I find this rather comforting. I appreciated the author's efforts at detailing the banal everydayness that co-exists with the crazy: food, traffic, clothing, cleaning. The turbulent 1960s are noted here and there as Ruth is ambivalent about Bruce and his college-bred revolutionary airs and his designs on Sara. Ammie is also, as many of these pop novels are, charmingly dated: endless miniskirts, dudes with long hair, Ruth's old-lady attitudes (she's only in her 40s! She's never eaten pizza!), Bruce's hip-academic pretensions. Sometimes this aspect is less charming: gender normativity/misogyny out the wahoo in Prof's not-so-subtle lechery, and the time Bruce declares there are "women you rape and women you marry." Yee-ow.

Barbara Mertz (1927 - 2013)

aka Barbara Michaels, aka Elizabeth Peters

As the origins of the possession become clearer, our narrative becomes tauter: Bruce learns more about the home and its literal foundations ("the whole house is rotten with hate"). A friendly Father figure is enlisted to aid in an exorcism and this goes poorly. Then the old Prof isn't so above-it-all as he'd like to appear; is he part of what seems to be a historical reenactment from beyond? The back-story is satisfyingly unsettling; you'll agree it's a crime that deserves retribution through the ages. Ammie, Come Home ends on a note of sentiment, but it is only the beginning in a three-book series that Michaels continued into the 1990s. I found the novel to be decidedly okay and won't be reading the rest; go ahead and check it out if you think you'll dig a quaint snapshot of the supernatural '60s and a helluva generation gap.

Postscript: for two other takes on the novel, check out Dark Chateaux and The Midnight Room. And thanks for the pix guys!

Thursday, April 7, 2016

Tuesday, October 27, 2015

Les Daniels Born Today in 1943

Born on this date in 1943 was Les Daniels, the creator of the vampire Don

Sebastian de Villanueva, who found his evil was often outshone by

humanity's historical horrors, in a series of novels published from the late '70s to the early '90s. He was

also a horror and comix expert of some note (Daniels, not Don

Sebastian). Daniels died in 2011. I read No Blood Spilled several years ago and really dug it and look forward to reading these other titles.

Sunday, October 4, 2015

And the Dawn Don't Rescue Me

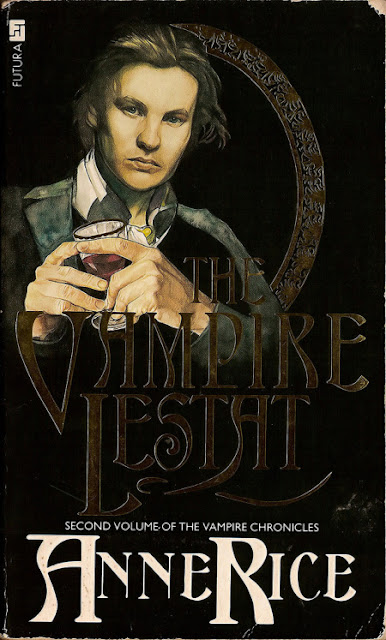

Vampire chronicler Anne Rice was born in New Orleans on this date in 1941. Above is a 1985 reprint of the original 1976 Interview with the Vampire (see earlier paperbacks, with stunning covers, here and here). Below are the later 1980s paperbacks, as she continued the tales of her undead brood and became a mega-bestselling author. I kinda like that they don't look like genre novels, featuring only big bold lettering.

These next three are the UK paperbacks, published by Futura throughout the '80s and early '90s.The cover for this reprint of Interview is the same art as the original 1977 edition.

I loved these books when I read them in the late 1980s. Rich, epic, decadent, thought-provoking and a whole lot of fun, I enjoyed them so much and recall them so fondly I'm rather reluctant to reread them today...

These next three are the UK paperbacks, published by Futura throughout the '80s and early '90s.The cover for this reprint of Interview is the same art as the original 1977 edition.

The author in 1979

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)