According to various Goodreads and online reviews, these are more police procedural/serial killer thrillers, and at least one, Without Mercy by "Leonard Jordan"—another pseudonym, this one used by prolific pulp writer Len Levinson—is worth a read.

Showing posts with label serial killer. Show all posts

Showing posts with label serial killer. Show all posts

Friday, March 25, 2022

Some Say Love It is a Razor

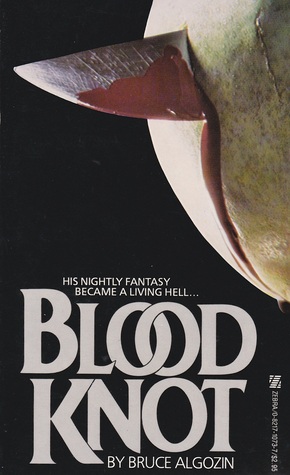

In the early and mid Eighties Zebra cranked out a handful of paperbacks that featured photos of knives slicing through various fruit, and in one case, a rose—not too obvious now! You'll recognize a few names: Joe Lansdale's first novel, Act of Love; two from hack supreme William W. Johnstone; and two from "Philip Straker," an pseudonym of Edward Lee, who would become a prolific extreme horror author in later years, and from what I can tell, he has disowned these two early titles.

Thursday, May 14, 2020

By Reason of Insanity by Shane Stevens (1979): Master of Reality

Today the serial killer is as common a stock character in popular entertainment as the kooky neighbor or the cranky dad. True crime, whether book, TV, or podcast, is bigger than ever. Yes, yes, it was always available in vast quantities, but so much of it seemed only steps removed from the tacky tabloid racks. Now it's about as classy as you can get, and as au courant ("Reading murder books/Trying to stay hip" as Billy Idol once sang). However, one of the foundational building blocks of the perception of serial killers as fictional mainstay has been forgotten, a work which has amassed a cult following in the 40 years since its release.

Published several years prior to Red Dragon, Thomas Harris's famous bestseller that introduced the world to Hannibal Lecter and Francis Dolarhyde, Insanity may be the first mainstream depiction of a serial killer as we know him today. With a journalist's objective pen, displaying the somber quality of a nonfiction account, Insanity first recounts the case of execution of Caryl Chessman, a real-life rapist whose shadow will encompass the entire novel. Quickly we move on to the travails of a young woman named Sara Bishop, 21, who will become the mother of one Thomas Bishop... the result of her rape by, she believes, Chessman himself. Sara's resentment, indeed hatred, of men, all men, with a passion others usually reserved for love, foreshadows her son's future disgust at womankind.

Sara abuses child Thomas beyond belief (In September Sara bought a whip), until of course the day he snaps and murders her and consumes part of her corpse before burning the body. He is found several days later in their isolated house, and authorities commit him to the Willows, a state mental hospital in northern California. There he grows up, plagued by female demons in his nightmares and so consumed with anger the doctors use shock therapy to treat him. Bishop realizes his only chance of ever escaping is to submit dutifully to authority, which he does, gaining their trust and more independence. He befriends another homicidal young man, Victor Mungo, all the while devising a plan to break out into the unwitting world. His escape is ingenious and ensures his identity will remain a mystery to those who wish to capture him. He was the master of reality, and he held life and death in his hands.

Thus ends Book One, "Thomas Bishop," and begins Book Two, "Adam Kenton." We've already met Kenton, as well as many of the other men who are spearheading the attempts at identifying Bishop and capturing him. But now Stevens delves further into Kenton: a successful journalist—nay, the most successful journalist!—in the biz. His skills at getting people to talk to him is thanks to an ability to become like them, no matter what walk of life they're from, are well-known among his colleagues; he can even, in a way, predict his subjects' thoughts. This mental bit of magic, grounded in voluminous information and a brilliant imagination, probably more than anything else had led to the nickname of Superman given him by his peers, not without a strong touch of envy.

This extraordinary skill comes at a cost of his personal life: Kenton's views of women are about as worrisome as Bishop's except not as deadly, a sad irony Kenton is at least aware of. In other words, he's a proto-serial killer profiler, the perfect person to go after Bishop, and hired by a major news magazine in secret to find the killer himself... out-thinking even the various hardened cops and experienced psychiatrists also working the case. Bishop, although a cause célèbre in all media now and virtually a household word, takes a backseat in this section to the dozens of characters who are eager to be on his trail in one way or another. Book Three, "Thomas Bishop and Adam Kenton," natch, will ante up the suspense as Bishop plans his ultimate apocalypse against womankind, and the two men finally come to their ultimate, maybe even predestined, fates. The voice on the other end was distant, metallic, funereal. "It has already begun." Kenton heard the soft click as the line went dead.

This is not to say that Insanity is perfect; invariably, weaknesses and fault lines appear. A book this large will have to have a few. One is the sheer quantity of characters (all men) who, if one is not careful, can be difficult to tell apart. Mob guys and cheap hoods and cheating husbands and surly blue collar workers and calculating media leaders and vengeful fathers and crooked politicians populate Insanity, and that can be a chore to read sometimes. Few are depicted with much warmth, as virtually all are overworked, shrewd, gruff, seen-it-all types who grouse and resent, men in high-pressure, difficult jobs whether legal or not (or some melange thereof, like Senator Jonathan Stoner—the story takes place during the Age of Nixon), men at the top who want to stay there or are desperate to get there. During his sojourn, Stoner been introduced to some political favorites, women of beauty and quality who were apparently turned on only by men of enormous political power.

Scenes of graphic sexual violence are depicted in a grim, matter-of-fact manner, unflinching, unblinking, Bishop's bloodletting a Jack the Ripper-style Grand Guignol directed at women he ties up for photo shoots when he pretends to be a photographer for True Detective magazine. The relentless subjugation of women may wear on some readers; the era of the story accounts for some of it, obviously, as does the subject matter, so while accurate for time and place, it might be a deal-breaker. He removed and fondled the girl's organs again and again, caressing them, needing to touch them, to possess them.

Maybe it's my pandemic brain, but I did grow a mite weary past the two-thirds mark. There are many unrelieved pages of police procedural, behind-the-scenes wheeling and dealing of mental health professionals, harried journalists, media moguls, and ambitious politicians doing their thing. It is 1973 here, and 1973 had no serial killer profilers or DNA database, when all the work was grinding away at newspaper clippings, hospital paper files, and endless phone calls (recall Fincher's Zodiac). There is no judgment on all their crudities, bigotries, and prejudices of characters which may unsettle some modern readers. Stevens spares us nothing. Maybe he was part Mexican, what kind of name was Spanner anyway?

We always know who the killer is, and it can be tiresome to read about each investigator's wrong ideas at such great length. What's the point? ("Probably moot," as Rick Springfield once sang). Too much time is spent away from Bishop and his psychopathic grandiosity, and often his exploits are off-screen as it were, sometimes graphic, sometimes unseen: inconsistently written, Stevens veers in style from cold hard non-fiction facts to lurid men's magazine pulp to hard-boiled detective to political thriller to guttural horror. It won't surprise you to learn that there are some last-minute twists and turns that I'm not convinced were successful, or necessary. Both men were shaken. Everything they knew to be substance had suddenly become shadow.

Still and all, By Reason of Insanity offers a lot of high-value, gruesome diversion for readers with lots of time on their hands; it's a blistering exposé of a ruthless, remorseless killing machine overloaded with ego and delusional self-regard, while men ironically not entirely unlike it try to extinguish its very existence. But it exists still, and Shane Stevens has exquisitely, if imperfectly, mapped out its hellish identity for all to see.

The reclusive author in 1970

I'm talking about By Reason of Insanity, an armored tank of crime, horror, and police procedural by crime author Shane Stevens (1941-2007), published in hardcover in 1979 with a Dell paperback issued in February 1980. Apparently it was a big deal back in its day—see the publisher's PR below—and even lauded as an inspiration by Stephen King in an afterword to his 1989 novel The Dark Half. But it's been eclipsed by its countless imitators, alas, as has its author.

Shane Stevens was probably born in Hoboken

in 1941 and raised in Harlem. He was attuned to the streets and the

people who made their lives there. Early novels, published in the

Sixties and Seventies, were about juvenile delinquents, black and white

gangs, the mob, class and money, "the dark side of the American Dream,"

as King put it in his Dark Half afterword. I haven't read any of his other novels, although I gather Insanity was the logical next step for Stevens. With By Reason of Insanity

he reached the big leagues of American publishing, but he'd write only

one more novel after that, and then, silence. While it's been in print

in various paperback editions over the years, no movie adaptation was

ever made, and today it is mostly forgotten except by adventurous

readers seeking the obscure.

Simon & Schuster hardcover, 1979

Published several years prior to Red Dragon, Thomas Harris's famous bestseller that introduced the world to Hannibal Lecter and Francis Dolarhyde, Insanity may be the first mainstream depiction of a serial killer as we know him today. With a journalist's objective pen, displaying the somber quality of a nonfiction account, Insanity first recounts the case of execution of Caryl Chessman, a real-life rapist whose shadow will encompass the entire novel. Quickly we move on to the travails of a young woman named Sara Bishop, 21, who will become the mother of one Thomas Bishop... the result of her rape by, she believes, Chessman himself. Sara's resentment, indeed hatred, of men, all men, with a passion others usually reserved for love, foreshadows her son's future disgust at womankind.

Sara abuses child Thomas beyond belief (In September Sara bought a whip), until of course the day he snaps and murders her and consumes part of her corpse before burning the body. He is found several days later in their isolated house, and authorities commit him to the Willows, a state mental hospital in northern California. There he grows up, plagued by female demons in his nightmares and so consumed with anger the doctors use shock therapy to treat him. Bishop realizes his only chance of ever escaping is to submit dutifully to authority, which he does, gaining their trust and more independence. He befriends another homicidal young man, Victor Mungo, all the while devising a plan to break out into the unwitting world. His escape is ingenious and ensures his identity will remain a mystery to those who wish to capture him. He was the master of reality, and he held life and death in his hands.

Carroll & Graf reprint, 1990

Now a free man at 25 years old, Bishop uses techniques learned from television crime shows to hide his true identity and gain new ones. Indeed, the authorities will have no idea who he is, and once his mutilated victims begin to turn up, their massive manhunt is futile. Bishop is on the move, and he's procured cash, driver's license, birth certificate, bank account, disappearing into the slipstream of modern life. He is attractive, charming, non-threatening, the consummate sociopathic actor, eager to outwit his pursuers as he fulfills and ritualizes his obsessive, narcissistic fantasies. Filled with unceasing rage against all women, Bishop

embarks on the most savage killing spree the world—the world of 1973,

that is—has ever seen. His wake was strewn with the butchered

bodies of the enemy and as in any war of diabolic purpose, no mercy was

expected and none given.

He starts a relationship with one older, moneyed woman so convincing they plan to marry... until they don't. Los Angeles, Las Vegas, towns across the country by train to, of course, New York City. By this time he is happily famous, taking delight in how the nation is reeling before him in terror, and he boldly announces his arrival in the Big Apple by leaving a dead woman in her train cabin. In the official lexicon of New York City, the date eventually came to be known as Bloody Monday.

He starts a relationship with one older, moneyed woman so convincing they plan to marry... until they don't. Los Angeles, Las Vegas, towns across the country by train to, of course, New York City. By this time he is happily famous, taking delight in how the nation is reeling before him in terror, and he boldly announces his arrival in the Big Apple by leaving a dead woman in her train cabin. In the official lexicon of New York City, the date eventually came to be known as Bloody Monday.

Sphere UK paperback, 1989

Thus ends Book One, "Thomas Bishop," and begins Book Two, "Adam Kenton." We've already met Kenton, as well as many of the other men who are spearheading the attempts at identifying Bishop and capturing him. But now Stevens delves further into Kenton: a successful journalist—nay, the most successful journalist!—in the biz. His skills at getting people to talk to him is thanks to an ability to become like them, no matter what walk of life they're from, are well-known among his colleagues; he can even, in a way, predict his subjects' thoughts. This mental bit of magic, grounded in voluminous information and a brilliant imagination, probably more than anything else had led to the nickname of Superman given him by his peers, not without a strong touch of envy.

This extraordinary skill comes at a cost of his personal life: Kenton's views of women are about as worrisome as Bishop's except not as deadly, a sad irony Kenton is at least aware of. In other words, he's a proto-serial killer profiler, the perfect person to go after Bishop, and hired by a major news magazine in secret to find the killer himself... out-thinking even the various hardened cops and experienced psychiatrists also working the case. Bishop, although a cause célèbre in all media now and virtually a household word, takes a backseat in this section to the dozens of characters who are eager to be on his trail in one way or another. Book Three, "Thomas Bishop and Adam Kenton," natch, will ante up the suspense as Bishop plans his ultimate apocalypse against womankind, and the two men finally come to their ultimate, maybe even predestined, fates. The voice on the other end was distant, metallic, funereal. "It has already begun." Kenton heard the soft click as the line went dead.

Its ambition prefigures writers like James Ellroy and of course Thomas

Harris; I was also reminded of Michael Slade's Headhunter. A massive, dense 600 pages in tiny print, Insanity is a powerhouse, brimming with dozens of characters, appalling violence, intricate

detective work, emotional distress. It's been on my shelves for years, and I was never sure when I wanted to take the deep dive into it. But once begun, it is virtually unstoppable. Stevens' style is big and bold, no frills; he takes you step-by-step through the creation of evil. This is big, baby, and you better be ready for it. The leisurely Eisenhower days were over and soon Kennedy would begin the years of Camelot.

There's an authority in his voice from the first, as he lays down a solid historical structure upon which to build his massive edifice of crime and terror. A precise documentation of the places and personalities that birth such a man as Thomas Bishop. The structure is epic; a widescreen panorama of our American life, from the Fifties to the early Seventies, a world populated by small-time hoods all the way to, yes, the White House. That's how far the ripples of Bishop's crimes reach, and every person touched by them will react according to their nature. Henry Baylor did not believe in premonitions. He was a doctor, a scientist of the mind. Precognition and inner voices were components of the occult, and the occult quite properly had no place in the discipline of science.

There's an authority in his voice from the first, as he lays down a solid historical structure upon which to build his massive edifice of crime and terror. A precise documentation of the places and personalities that birth such a man as Thomas Bishop. The structure is epic; a widescreen panorama of our American life, from the Fifties to the early Seventies, a world populated by small-time hoods all the way to, yes, the White House. That's how far the ripples of Bishop's crimes reach, and every person touched by them will react according to their nature. Henry Baylor did not believe in premonitions. He was a doctor, a scientist of the mind. Precognition and inner voices were components of the occult, and the occult quite properly had no place in the discipline of science.

This is not to say that Insanity is perfect; invariably, weaknesses and fault lines appear. A book this large will have to have a few. One is the sheer quantity of characters (all men) who, if one is not careful, can be difficult to tell apart. Mob guys and cheap hoods and cheating husbands and surly blue collar workers and calculating media leaders and vengeful fathers and crooked politicians populate Insanity, and that can be a chore to read sometimes. Few are depicted with much warmth, as virtually all are overworked, shrewd, gruff, seen-it-all types who grouse and resent, men in high-pressure, difficult jobs whether legal or not (or some melange thereof, like Senator Jonathan Stoner—the story takes place during the Age of Nixon), men at the top who want to stay there or are desperate to get there. During his sojourn, Stoner been introduced to some political favorites, women of beauty and quality who were apparently turned on only by men of enormous political power.

Scenes of graphic sexual violence are depicted in a grim, matter-of-fact manner, unflinching, unblinking, Bishop's bloodletting a Jack the Ripper-style Grand Guignol directed at women he ties up for photo shoots when he pretends to be a photographer for True Detective magazine. The relentless subjugation of women may wear on some readers; the era of the story accounts for some of it, obviously, as does the subject matter, so while accurate for time and place, it might be a deal-breaker. He removed and fondled the girl's organs again and again, caressing them, needing to touch them, to possess them.

Maybe it's my pandemic brain, but I did grow a mite weary past the two-thirds mark. There are many unrelieved pages of police procedural, behind-the-scenes wheeling and dealing of mental health professionals, harried journalists, media moguls, and ambitious politicians doing their thing. It is 1973 here, and 1973 had no serial killer profilers or DNA database, when all the work was grinding away at newspaper clippings, hospital paper files, and endless phone calls (recall Fincher's Zodiac). There is no judgment on all their crudities, bigotries, and prejudices of characters which may unsettle some modern readers. Stevens spares us nothing. Maybe he was part Mexican, what kind of name was Spanner anyway?

We always know who the killer is, and it can be tiresome to read about each investigator's wrong ideas at such great length. What's the point? ("Probably moot," as Rick Springfield once sang). Too much time is spent away from Bishop and his psychopathic grandiosity, and often his exploits are off-screen as it were, sometimes graphic, sometimes unseen: inconsistently written, Stevens veers in style from cold hard non-fiction facts to lurid men's magazine pulp to hard-boiled detective to political thriller to guttural horror. It won't surprise you to learn that there are some last-minute twists and turns that I'm not convinced were successful, or necessary. Both men were shaken. Everything they knew to be substance had suddenly become shadow.

Still and all, By Reason of Insanity offers a lot of high-value, gruesome diversion for readers with lots of time on their hands; it's a blistering exposé of a ruthless, remorseless killing machine overloaded with ego and delusional self-regard, while men ironically not entirely unlike it try to extinguish its very existence. But it exists still, and Shane Stevens has exquisitely, if imperfectly, mapped out its hellish identity for all to see.

They were all secretly jealous of him. He was doing what they couldn't do, what they longed to do if only they weren't so cowardly. He was fulfilling all their deepest desires, their unconscious cravings. And why not? They were men and had the same chance he had. Only he took his chances. He showed them all up, and so they were angry with him...

Friday, July 5, 2019

Koko by Peter Straub (1988): Born Down in a Dead Man's Town

Peter Straub's entry into this cultural reckoning of the conflict was his ambitious 1988 novel Koko (Signet Books paperback, July 1989, cover by Robert Korn). One of the most ubiquitous of all 1980s paperback novels found in many a used bookstore's horror section, Koko's cover art of primary colors and thick, high-contrast spine has captured my eye for years. It wasn't ever very high on my to-read list, however, as I knew it was more mainstream thriller and that it dealt with Vietnam, which was not my thing at all when I was in my early twenties (despite the fact that I was devouring films like the aforementioned Deer Hunter and Apocalypse Now, but that was because they happened to be great '70s movies, not because they were about Vietnam). How glad I am that I finally took the leap and read it!

Straub in 1988

Straub's book is about four men, Vietnam vets who served together, on a journey, circling around a secret, a secret unknowable and unimaginable, a secret that may not even have happened: a Schrodinger's cat event of battletime horror. Michael Poole, Harry Beevers, Tina Pumo, Conor Linklater: a children's doctor whose marriage is breaking up, an asshole lawyer, a NYC restaurateur in over his head, an unambitious carpenter. In shades of Straub's horror breakthrough Ghost Story (1979), these men live their lives around a horrible event; in this case, something that happened in a cave in the Vietnamese village of Ia Thuc during the war, akin to the real-life My Lai massacre. Koko opens with a powerful, resonant, emotional scene of the men reuniting after more than a decade in Washington DC to visit the Vietnam Memorial:

For Poole, the actual country of Vietnam was now just another place... its history and culture had briefly, disastrously intersected ours. But the actual country of Vietnam was not Vietnam; that was here, in these American names and faces.

Having learned of a serial killer named Koko in southeast Asia who may be one of their fellow vets from their old combat unit, the four men begin an international search: Beevers, Poole, and Linklater travel to Asia to track him down; Pumo remains in New York and deals with the demons of restaurant management and a one-night stand that goes horribly wrong. Visiting Singapore and Bangkok, the three men begin searching for answers no one can give them, carousing East Asian bars and whorehouses, being taken to secret shows in dingy basements where humans are killed for expensive thrills, plumbing their own natures in that Heart of Darkness manner. These colorful travelogue sequences are interspersed with scenes from the war, and we meet the other soldiers in their unit: Manuel Dengler, Tim Underhill, Victor Spitalny... who is Koko? What is Koko? Fortunate reader, you will learn.

In the eerie and violent chapters featuring the title character, Koko's psychic state reminds me very much of Francis Dollarhyde in Red Dragon: the cunning, the mania, the grandiosity, the sick poetry of it, and this bit about "the nearness of ultimate things." It's a dead-eyed glare, an interiorized fantasy world so powerful that he must remake the real world in trauma. While Straub does not trade in the same forensic ingenuity as that Thomas Harris title, the madnesses of men and its origins are kindred: "God's hand hung in the air, pointing at him."

By far my favorite sequence—in a novel filled with great sequences—is a trip to Milwaukee to track down Spitalny's and Dengler's families. This visit to a sad, broken, gloomy town to speak with sad, broken, gloomy people is a glimpse into a part of America that isn't a beacon of shining hope: these are people with petty approaches to life, who exile themselves from the main street of life and gloat over past pain, who never seem to grow out of the small-minded provincialites, who cripple themselves and indulge in the small sick sadistic voice that whispers of their inadequacy and vanity. Small-town America, as horror reminds us over and over and over, is rife with the evil of banality.

This is the kind of full-on novel that takes up a lot of space in your head; this review has touched on only a portion of what it offers. Straub's fine and thoughtful prose, rich vein of humanity, eye and ear for marital discord, and ability to launch widescreen emotional horrors of deep, profound impact, will satisfy the discerning reader. For such a thick tome (600 pages), the story moves along weightlessly, fleet-footed yet penetrating, disturbing but empathetic, never bogged down in useless detail or dialogue, everything in its right place. The climax is in another unlit cavern in a modern American city, where everything meets one final time, where "eternity happened all at once, backwards and forward."

Reviews found online range from "masterpiece" to "meh," but I can tell from some of those "meh"s that the readers were expecting a giant feast of guttural horror—which Koko surely is not. Two volumes follow in a very loose trilogy: Mystery (1990) and The Throat (1993), and I know little about either, but I've added them to my must-read list. It might not be a perfect novel—perhaps at times its sights are beyond its reach—but for the adventurous horror fan who doesn't mind the occasional foray into non-supernatural madness, who is ready for a huge armored tank of a book that looks into one of America's darkest eras... Koko is singing a song you'll want to hear.

Couldn't believe Straub himself retweeted me...!

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)