So I'm well chuffed to report that Ramsey Campbell's 1989 novel Ancient Images (Tor paperback, June 1990, art by Gary Smith) ticks all those boxes successfully. A measured, mature, and well-paced thriller that finds the prolific modern master Campbell plying his quiet horror trade in top form, I devoured this book in a matter of days, eager to get back to it every time I had to put it down.

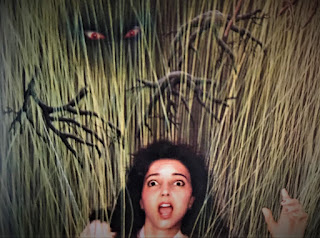

Campbell in 1989, photo by JK Potter

Interestingly, the impetus here is utterly modern: the search for a lost (fictional) film. Tower of Fear stars horror icons Boris Karloff and Bela Lugosi, produced during the same era as their real dual-starrers like The Black Cat (1934) and The Body Snatcher (1945). Graham Nolan is a film critic for television news who has finally tracked down a copy of the film, suppressed and never released, after searching for it for two years. He invites his colleague, film editor Sandy Allan, from the TV station they work at, to watch it with him. When Sandy arrives at Graham's apartment that evening for the "premiere," she finds it's been ransacked, the film projector knocked over and empty film canisters strewn about... and no copy of Tower of Fear. Then she sees Graham on the roof of the adjacent building, and as Sandy rushes to an outer door, she can only watch in horror as he tries to leap back to his own building, but misses and falls to his death:

His mouth was gaping, silenced perhaps by the wind of his fall, and yet she thought he saw her and, despite his terror, managed to look unbearably apologetic, as if he wanted her to know that it wasn't her fault she hadn't been in time to reach him.

Upon learning of the rarity of the film, the police think that Graham chased a thief across the rooftops. Sandy thinks this makes as much sense as anything, and writes an obituary for Graham to be broadcast by the station, mentioning his search for Tower of Fear and its theft. A day later a snarky tabloid critic who knew Graham pays him a backhanded tribute in print, angering Sandy by the dent it makes in Graham's integrity. She confronts this pompous writer, Len Stilwell, at a horror movie premiere with American film historian Roger Stone (our eventual love interest). Stilwell dismisses the two of them and their mission: "I write consumer reports, I've no time for cleverness. Nor to argue." Wow do you wanna smack the guy! (Was Campbell inspired by a real-life critic?!)

Armed with Graham's notebook that contains contact info of people who'd worked on and starred in the film so many decades before, Sandy begins tracking them down, determined to save Graham's reputation. The mystery grows, for director Giles Spence was killed in a car accident just after filming ended. Karloff and Lugosi themselves never spoke of it. Like so many novels before and since, this research quest is a pleasure to read. What sinister force made this movie such a troubled production, caused it to be banned, led its makers and stars into seclusion, secrecy, even death? I mean, I love this kinda shit!

Campbell shines as he creates the unique characters Sandy meets. To a one they seem agitated, even fearful, to have Tower of Fear brought up again and again; many principals are aging and their adult children don't want their parents bothered by some trash horror nonsense from long ago. Even Sandy's parents are put off by it, although Dad admits, "Neither your mother nor I have heard of it, though it's the kind of thing we would have lapped up before the war changed all that."

Sandy meets the editors and designers and and writers and actors who were involved with Tower of Fear, and as I said, it's a pleasure to read; Sandy is a smart and capable character. She even hangs out with a disreputable group of grungy young movie fans who put out a gore zine. His fictional cinematic creations and their intersection with real-life movie culture isn't cute or self-aware, nor is it pretentious or faux-intellectual (*cough* Flicker *cough*), it simply is.

But it's the creeping unease when dealing with those who helped make the movie, the paranoia and distrust, which Campbell conveys with such subtle mastery, that propels the novel forward. There are also notes of tragedy, particularly in the sad career of once-popular actor Tommy Hoddle, who'd provided the comic relief for Tower of Fear. Sandy tracks him to down at a beach resort town where he is playing in children's afternoon theater shows, this one a pathetic vampire spoof. She tries to engage him about the movie, to no avail, and succeeds only in terrifying the poor old chap...

Eventually, after much to-do that involves a burgeoning affair with Stone, professional pressures, and figures that flitter and caper just at the edge of perception—that hallmark of Campbell's off-kilter approach to chills and dread—Sandy finds the owner of the movie rights. This is Lord Redfield, of the township Redfield, known far and wide for its successful agriculture which provides the wheat for Staff o' Life bread, a popular brand whose commercials always seem to be playing in the background. Lord Redfield invites Sandy to his palatial home, and in Bond villain fashion, explains (almost) all to her. Political strings and newspaper ownership factor in, but there are still unsettling questions in Sandy's mind about the film and its relationship to Redfield... and sullen locals to avoid. She scales an historic tower, obviously the inspiration for the film, and traipses through the cemetery, where death dates have an uncomfortable 50-year regularity going back centuries. And that name: red... field. Uhhh, that can't be good. Folk horror fully engaged!

And I haven't even mentioned Enoch's Army. What's Enoch Army? It's a sort of leftover band of hippie revolutionaries who are trudging in a caravan through parts of England, looking for a safe haven to call home, but tabloids are biased against them (guess who owns one of those tabloids). Tensions are rising as no one wants these folks around. Campbell has them on a parallel with the search for Tower of Fear, both literally and figuratively. During her travels, Sandy comes across them in the road with police escort, but one of the children runs in front of her car and she nearly hits him and his mother. Apologetic, Sandy talks with them and then the leader himself, Enoch Hill. His words form the thematic core of the novel:

Basically, Enoch himself made me think of Alan Moore.

All these disparate elements are steadily making their way towards one another in Campbell's sure hand: Enoch's Army, those strange twig-like shadows hovering at the corners of the narrative, Lord Redfield, Tower of Fear, the harvest... step by careful unavoidable step. Beautifully paced, restrained, subtle, and intriguing, I've only sketched the aspects that make this such a satisfying read; it has to be one of Campbell's very finest works of the Eighties. It's also cool that Campbell is no mean film critic and fan himself, so you just know he had a high old time writing it (and he thanks our old pal Dennis Etchison in the notes for his help with cinematic minutiae).

Like the atmospheric black-and-white movies of the past that Campbell invokes, there is scarcely a drop of blood, but there is a great deal of suspense and mystery. If you love film history and behind-the-scenes accounts of film-making, the trappings of folk horror, or a sharp, well-crafted tale, this is a must-read. Ancient Images is also a great place to start if you've never read a Campbell novel. No doubt about it: this is a masterful piece of quiet horror. That quiet, however, just means you can't hear what's sneaking up behind you.

Armed with Graham's notebook that contains contact info of people who'd worked on and starred in the film so many decades before, Sandy begins tracking them down, determined to save Graham's reputation. The mystery grows, for director Giles Spence was killed in a car accident just after filming ended. Karloff and Lugosi themselves never spoke of it. Like so many novels before and since, this research quest is a pleasure to read. What sinister force made this movie such a troubled production, caused it to be banned, led its makers and stars into seclusion, secrecy, even death? I mean, I love this kinda shit!

Campbell shines as he creates the unique characters Sandy meets. To a one they seem agitated, even fearful, to have Tower of Fear brought up again and again; many principals are aging and their adult children don't want their parents bothered by some trash horror nonsense from long ago. Even Sandy's parents are put off by it, although Dad admits, "Neither your mother nor I have heard of it, though it's the kind of thing we would have lapped up before the war changed all that."

Legend Books UK, 1990

Sandy meets the editors and designers and and writers and actors who were involved with Tower of Fear, and as I said, it's a pleasure to read; Sandy is a smart and capable character. She even hangs out with a disreputable group of grungy young movie fans who put out a gore zine. His fictional cinematic creations and their intersection with real-life movie culture isn't cute or self-aware, nor is it pretentious or faux-intellectual (*cough* Flicker *cough*), it simply is.

But it's the creeping unease when dealing with those who helped make the movie, the paranoia and distrust, which Campbell conveys with such subtle mastery, that propels the novel forward. There are also notes of tragedy, particularly in the sad career of once-popular actor Tommy Hoddle, who'd provided the comic relief for Tower of Fear. Sandy tracks him to down at a beach resort town where he is playing in children's afternoon theater shows, this one a pathetic vampire spoof. She tries to engage him about the movie, to no avail, and succeeds only in terrifying the poor old chap...

Eventually, after much to-do that involves a burgeoning affair with Stone, professional pressures, and figures that flitter and caper just at the edge of perception—that hallmark of Campbell's off-kilter approach to chills and dread—Sandy finds the owner of the movie rights. This is Lord Redfield, of the township Redfield, known far and wide for its successful agriculture which provides the wheat for Staff o' Life bread, a popular brand whose commercials always seem to be playing in the background. Lord Redfield invites Sandy to his palatial home, and in Bond villain fashion, explains (almost) all to her. Political strings and newspaper ownership factor in, but there are still unsettling questions in Sandy's mind about the film and its relationship to Redfield... and sullen locals to avoid. She scales an historic tower, obviously the inspiration for the film, and traipses through the cemetery, where death dates have an uncomfortable 50-year regularity going back centuries. And that name: red... field. Uhhh, that can't be good. Folk horror fully engaged!

US hardcover, cover art by Don Brautigam

And I haven't even mentioned Enoch's Army. What's Enoch Army? It's a sort of leftover band of hippie revolutionaries who are trudging in a caravan through parts of England, looking for a safe haven to call home, but tabloids are biased against them (guess who owns one of those tabloids). Tensions are rising as no one wants these folks around. Campbell has them on a parallel with the search for Tower of Fear, both literally and figuratively. During her travels, Sandy comes across them in the road with police escort, but one of the children runs in front of her car and she nearly hits him and his mother. Apologetic, Sandy talks with them and then the leader himself, Enoch Hill. His words form the thematic core of the novel:

"Our way is to move on when the land wants to rest and dream, but the mass of men won't leave it alone. Man and the land used to respect each other, but now man pollutes the land...There'll come a day when the earth demands more of man than it ever did when man knew what it wanted... All fiction is an act of violence... Man can't resume his old relationship with the earth until we remember the tales that told the truth. We had a blueprint for living, and civilization tore it up."

Basically, Enoch himself made me think of Alan Moore.

UK hardcover

All these disparate elements are steadily making their way towards one another in Campbell's sure hand: Enoch's Army, those strange twig-like shadows hovering at the corners of the narrative, Lord Redfield, Tower of Fear, the harvest... step by careful unavoidable step. Beautifully paced, restrained, subtle, and intriguing, I've only sketched the aspects that make this such a satisfying read; it has to be one of Campbell's very finest works of the Eighties. It's also cool that Campbell is no mean film critic and fan himself, so you just know he had a high old time writing it (and he thanks our old pal Dennis Etchison in the notes for his help with cinematic minutiae).

Like the atmospheric black-and-white movies of the past that Campbell invokes, there is scarcely a drop of blood, but there is a great deal of suspense and mystery. If you love film history and behind-the-scenes accounts of film-making, the trappings of folk horror, or a sharp, well-crafted tale, this is a must-read. Ancient Images is also a great place to start if you've never read a Campbell novel. No doubt about it: this is a masterful piece of quiet horror. That quiet, however, just means you can't hear what's sneaking up behind you.

She imagined the land was able to send something to hunt victims on its behalf...