According to various Goodreads and online reviews, these are more police procedural/serial killer thrillers, and at least one, Without Mercy by "Leonard Jordan"—another pseudonym, this one used by prolific pulp writer Len Levinson—is worth a read.

Showing posts with label joe lansdale. Show all posts

Showing posts with label joe lansdale. Show all posts

Friday, March 25, 2022

Some Say Love It is a Razor

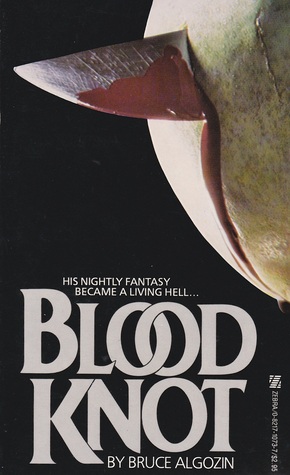

In the early and mid Eighties Zebra cranked out a handful of paperbacks that featured photos of knives slicing through various fruit, and in one case, a rose—not too obvious now! You'll recognize a few names: Joe Lansdale's first novel, Act of Love; two from hack supreme William W. Johnstone; and two from "Philip Straker," an pseudonym of Edward Lee, who would become a prolific extreme horror author in later years, and from what I can tell, he has disowned these two early titles.

Saturday, July 10, 2021

Intensive Scares: The Paperback Cover Art of J.K. Potter

Vintage horror fiction fans are well aware of American artist J.K. Potter, born Jeffrey Knight Potter in California on this date in 1956. His macabre photorealistic imagery decorated the covers of dozens of small-press hardcovers, various magazines, and plenty of paperbacks throughout the Eighties and beyond, most often for such genre heavyweights as Stephen King, Ray Bradbury, Ramsey Campbell, Dennis Etchison, Charles L. Grant, and Karl Edward Wagner, along with many other writers in the fantasy and science fiction fields as well.

Sunday, December 10, 2017

Fangoria Nightmare Library Reviews, February 1988

Another installment of Fangoria mag's vintage book reviews, thanks to TMHF reader Patrick B. Authors should be familiar to horror fans: Joe Lansdale, Whitley Strieber, Michael Talbot, Rex Miller, and Thomas Monteleone. And I myself have reviewed three of these titles: Lansdale's Nightrunners, Talbot's Bog, and Miller's Slob.

Thursday, August 3, 2017

By Bizarre Hands by Joe R. Lansdale (1989): Apocalypse Wow

If you were a horror fiction reader in the late 1980s and paid attention to such things, you knew that Joe R. Lansdale was being marketed, if that's not too strong a word, in a manner not seen since probably Clive Barker. Their respective publishers knew, even if they couldn't put their finger on it exactly, that these writers were incredibly special (this has nothing to do with the individual styles of Barker and Lansdale, which are markedly different, only that they both went further, deeper, harder, than other even very good writers of that age did) and deserved to be widely read. Check out the cover copy, front and back, of By Bizarre Hands (Avon Books, Sept 1991): "Renegade Nightmare King"?! "May Be Hazardous to Your Health"?! These types of superlatives reach higher than the usual boilerplate encomium, and worked to entice readers who wanted more than just the latest humdrum hack horror.

I was ecstatic to be reading Lansdale for the first time in various anthologies back then; like many readers I'd never read anything like him. Sure there was the Vonnegut and the Twain, the Mencken and the Joe Bob Briggs, the King and the Matheson and the Bradbury, here and there a whiff of Elmore Leonard and Harry Crews (I noted these last two much later as I had not read them on my first encounter with Lansdale). But still there was something original, tough and sure and daring that sang beneath those familiar notes... and I wanted more.

Around 1990 or so I paid big bucks for a signed copy of Joe's short story collection, the 1989 hardcover edition from specialty publisher Mark V. Ziesing. Consisting of his earliest as well as his major stories, I devoured it, loved it, but sometime later, during a bleak broke span during my college years, I had to sell off a major chunk of my limited-edition horror collection, so it was bye-bye By Bizarre. Ah well. Then a month or so ago a TMHF pal emailed a link to this Avon paperback edition from 1991, adorned with the same illustration as the hardcover, thanks to usual suspect JK Potter; it was in good shape and at a fair price, who doesn't love that. Sold! So it's great to have By Bizarre Hands back on my shelves. Couldn't wait to revisit Lansdale's singular landscape of horror, black humor, science fiction, crime, and whatever the hell else he puts in.

Lansdale often succeeds at impossible tasks, with setups that would make lesser writers blanch (or not even realize what deep waters they were in), and pulls them off with a tough, vulgar, self-conscious but not arch energy. He may wink at you but it's not a cute wink of "Hey we both know this is ridiculous" but a wink of devilish glee, acrobatic mischief, "You can't believe I'm getting away with this, can you?!" Like a sort of Tarzan swinging through the jungle hoping a vine will appear in the nick of time, you can't fault him because it all kinda takes your breath away even when his moves are occasionally clumsy or crude. His confidence and his trust in his own instincts, talent, character sketches, and unique vision thrills the reader, makes the reader forgive those tacky lapses scattered about (as if Lansdale were afraid of upsetting social niceties in the first place). YOU HAVE BEEN WARNED!

Let's get to the goods, right from the opener. "Fish Night," hearkens back to Bradbury's love of dinosaurs and other creatures of our earth's past, but lacks any wide-eyed nostalgic innocence. Nostalgic for the ravenous extinct monstrous creatures which swam that prehistoric sea, perhaps... "Duck Hunt" satirizes male camaraderie and companionship, machismo and violence masquerading as such. The terrific title story was also published in the first Borderlands (1990); I wrote a little about it here. It's tasteless, sure, sometimes you think, "Jeez, Joe, I didn't need to know all that," but that's just Joe: he's gonna give it to you straight, maybe chase it with pickle juice and gasoline. Then light the match.

Ever read any of the Black Lizard reprints of 1950s crime/hardboiled pulp fiction? Not just Jim Thompson, but Dan J. Marlowe, David Goodis, Charles Willeford? Written with pulp muscle and a refusal to sugar coat with any moralizing, Lansdale presents the criminal lifestyle as-is, no returns, no refunds. More than one tale here reminds me of those stark, sere, brutal crime novels, particularly "The Steel Valentine" and "The Pit." "I Tell You It's Love" revels in the romantic sadomasochism of James M. Cain. "Down By the Sea Near the Great Big Rock" is almost whimsical, a Gahan Wilson cartoon come to life. And three stories became three novels: "Boys Will Be Boys" part of The Nightrunners; "Hell Through a Windshield" is the beginnning of The Drive-In; "The Windstorm Passes" became The Magic Wagon. All are must-reads, both the stories here and the actual novels themselves.

One of the very best stories included is "Tight Little Stitches in a Dead Man's Back," the title alone which has bounced around in my head for 25 years even as the details faded, is a mean little masterpiece. It's funny, sad, disgusting, outrageous, insightful, empathetic, painful, humiliating, gory, unsettling, a near-effortless melange of SF and horror tropes. His weirdo SF is kinda mind-blowing. I'm not sure what apocalyptic authors Lansdale read—John Brunner? JG Ballard? John Wyndham?—but it's just powerhouse stuff nobody else could've written. Guilt, hatred, regret, only these human emotions survive the apocalypse, along with monstrous thorny vines and mutated animals. Behold the surreality:

The collection concludes with two of Joe's most infamous stories, late 1980s classics that made a splash then and still retain their power decades later: "Night They Missed the Horror Show" and "On the Far Side of the Cadillac Desert with Dead Folk." The former contains some of the ugliest, most blistering imagery and dialogue for its time, and isn't even really a "horror" story in the generic sense; it's the blackest of noir, maybe. Scorched earth policy here, a glimpse of unfettered human depravity and ignorance, outcast kin to the blistering art and exploitation of, say, Taxi Driver or Henry: Portrait of a Serial Killer or James Ellroy's LA Quartet. If you haven't read "Night They Missed the Horror Show," I can't say you've missed a treat but you have missed a milestone in extreme fiction. The latter tale, from the zombie universe of George A. Romero (RIP!), is a long rambling road story of bounty hunters and the undead, plus lots of Bible talk (a staple of many a Lansdale), gunplay, and gore. You won't be scared but you will be impressed by its colorful energy.

We all are aware of how unique voices can be forgotten, or become cult/fringe favorites, and never find a broader audience. Not so with Joe. It's satisfying to know that today he has a bigger following than ever, with a movie and TV series adapted from his work (Cold in July and Hap & Leonard, respectively), and more and more award-winning novels. He is a friendly and supportive online presence as well. Reading Joe Lansdale is a free-for-all. For the adventurous, unsatisfied reader who demands more, more, more, I can say get your hands on By Bizarre Hands; it is an essential and uncompromising read.

I was ecstatic to be reading Lansdale for the first time in various anthologies back then; like many readers I'd never read anything like him. Sure there was the Vonnegut and the Twain, the Mencken and the Joe Bob Briggs, the King and the Matheson and the Bradbury, here and there a whiff of Elmore Leonard and Harry Crews (I noted these last two much later as I had not read them on my first encounter with Lansdale). But still there was something original, tough and sure and daring that sang beneath those familiar notes... and I wanted more.

Around 1990 or so I paid big bucks for a signed copy of Joe's short story collection, the 1989 hardcover edition from specialty publisher Mark V. Ziesing. Consisting of his earliest as well as his major stories, I devoured it, loved it, but sometime later, during a bleak broke span during my college years, I had to sell off a major chunk of my limited-edition horror collection, so it was bye-bye By Bizarre. Ah well. Then a month or so ago a TMHF pal emailed a link to this Avon paperback edition from 1991, adorned with the same illustration as the hardcover, thanks to usual suspect JK Potter; it was in good shape and at a fair price, who doesn't love that. Sold! So it's great to have By Bizarre Hands back on my shelves. Couldn't wait to revisit Lansdale's singular landscape of horror, black humor, science fiction, crime, and whatever the hell else he puts in.

Lansdale often succeeds at impossible tasks, with setups that would make lesser writers blanch (or not even realize what deep waters they were in), and pulls them off with a tough, vulgar, self-conscious but not arch energy. He may wink at you but it's not a cute wink of "Hey we both know this is ridiculous" but a wink of devilish glee, acrobatic mischief, "You can't believe I'm getting away with this, can you?!" Like a sort of Tarzan swinging through the jungle hoping a vine will appear in the nick of time, you can't fault him because it all kinda takes your breath away even when his moves are occasionally clumsy or crude. His confidence and his trust in his own instincts, talent, character sketches, and unique vision thrills the reader, makes the reader forgive those tacky lapses scattered about (as if Lansdale were afraid of upsetting social niceties in the first place). YOU HAVE BEEN WARNED!

Let's get to the goods, right from the opener. "Fish Night," hearkens back to Bradbury's love of dinosaurs and other creatures of our earth's past, but lacks any wide-eyed nostalgic innocence. Nostalgic for the ravenous extinct monstrous creatures which swam that prehistoric sea, perhaps... "Duck Hunt" satirizes male camaraderie and companionship, machismo and violence masquerading as such. The terrific title story was also published in the first Borderlands (1990); I wrote a little about it here. It's tasteless, sure, sometimes you think, "Jeez, Joe, I didn't need to know all that," but that's just Joe: he's gonna give it to you straight, maybe chase it with pickle juice and gasoline. Then light the match.

Ever read any of the Black Lizard reprints of 1950s crime/hardboiled pulp fiction? Not just Jim Thompson, but Dan J. Marlowe, David Goodis, Charles Willeford? Written with pulp muscle and a refusal to sugar coat with any moralizing, Lansdale presents the criminal lifestyle as-is, no returns, no refunds. More than one tale here reminds me of those stark, sere, brutal crime novels, particularly "The Steel Valentine" and "The Pit." "I Tell You It's Love" revels in the romantic sadomasochism of James M. Cain. "Down By the Sea Near the Great Big Rock" is almost whimsical, a Gahan Wilson cartoon come to life. And three stories became three novels: "Boys Will Be Boys" part of The Nightrunners; "Hell Through a Windshield" is the beginnning of The Drive-In; "The Windstorm Passes" became The Magic Wagon. All are must-reads, both the stories here and the actual novels themselves.

One of the very best stories included is "Tight Little Stitches in a Dead Man's Back," the title alone which has bounced around in my head for 25 years even as the details faded, is a mean little masterpiece. It's funny, sad, disgusting, outrageous, insightful, empathetic, painful, humiliating, gory, unsettling, a near-effortless melange of SF and horror tropes. His weirdo SF is kinda mind-blowing. I'm not sure what apocalyptic authors Lansdale read—John Brunner? JG Ballard? John Wyndham?—but it's just powerhouse stuff nobody else could've written. Guilt, hatred, regret, only these human emotions survive the apocalypse, along with monstrous thorny vines and mutated animals. Behold the surreality:

The collection concludes with two of Joe's most infamous stories, late 1980s classics that made a splash then and still retain their power decades later: "Night They Missed the Horror Show" and "On the Far Side of the Cadillac Desert with Dead Folk." The former contains some of the ugliest, most blistering imagery and dialogue for its time, and isn't even really a "horror" story in the generic sense; it's the blackest of noir, maybe. Scorched earth policy here, a glimpse of unfettered human depravity and ignorance, outcast kin to the blistering art and exploitation of, say, Taxi Driver or Henry: Portrait of a Serial Killer or James Ellroy's LA Quartet. If you haven't read "Night They Missed the Horror Show," I can't say you've missed a treat but you have missed a milestone in extreme fiction. The latter tale, from the zombie universe of George A. Romero (RIP!), is a long rambling road story of bounty hunters and the undead, plus lots of Bible talk (a staple of many a Lansdale), gunplay, and gore. You won't be scared but you will be impressed by its colorful energy.

New English Library, 1992

We all are aware of how unique voices can be forgotten, or become cult/fringe favorites, and never find a broader audience. Not so with Joe. It's satisfying to know that today he has a bigger following than ever, with a movie and TV series adapted from his work (Cold in July and Hap & Leonard, respectively), and more and more award-winning novels. He is a friendly and supportive online presence as well. Reading Joe Lansdale is a free-for-all. For the adventurous, unsatisfied reader who demands more, more, more, I can say get your hands on By Bizarre Hands; it is an essential and uncompromising read.

Friday, January 6, 2017

Razored Saddles, ed. by Joe Lansdale & Pat LoBrutto (1989): One-Half Hillbilly and One-Half Punk

Boasting cover art that strikes a sweet spot between absurd and awesome, the wonderfully-titled Razored Saddles (Avon Books paperback, October 1990) rustles up a heap of horror/SF/western/whatever short fiction to boot. Edited by the always-welcome Texan Joe R. Lansdale and co-conspirator Pat LoBrutto, the anthology collects a hatful of recognizable genre names of the day, plus a few new to almost anybody. I remember this tome way back when thanks to that cover (thanks to Lee MacCleod) and its regrettable joke categorization on the spine, "cowpunk." But Western-themed anything had always been low in my interest level, and it pains me to say that my holiday reading of Razored Saddles reminded me why.

Another of Robert McCammon's pleasant, inoffensive horror tales, "Black Boots," begins the anthology. A cowboy is being followed across the desert by a gunslinger wearing the titular objects. He stops in a dusty small "town" to drink some watered-down whiskey but soon sees "Black Boots" at the door of the saloon. Ironic tragedy follows. Its touches of surrealism are well-noted, but McCammon's simplistic style neuters the creepiness and final twist.

"Thirteen Days of Glory" by Scott A. Cupp upends a famous Western showdown with a decidedly transgressive aspect. Freedom must be for everyone or for none at all. Not bad, rather daring, probably offensive to some and liberating for others. Cupp's story is engaging and yet sad, one of the few here that are memorable.

"Gold" by Lewis Shiner is strong, well-told, tinged by magic-realism (a style much favored by genre writerly-writers), set in Creole swamps with strong characterization, but it ends with a damp whimper as it goes into mind-numbing financial details. A huge letdown.

David J. Schow's "Sedalia" is just... weird. Not fun weird, not weird weird, but just kinda what? weird, a proto-bizarro tale of ghost dinosaurs, maybe some kind of fossil fuel metaphor. Taking its title from the old-as-dinosaurs TV show "Rawhide," we've got "drovers" herding those ghost dinos in some future Los Angeles. It's marred by juvenile talk of dinosaur poop and incomprehensible politics, although I appreciated the fact that characters refuse to call a brontosaurus an apatosaurus as it "seemed too-too." 2015 showed that was correct.

Introduced by the editors as a bit of "Weird Tales" or EC Comics, Ardath Mayhar's "Trapline" is precisely that: a fur-trapper and a gory comeuppance. Sure, why not, whatever. The late Melissa Mia Hall, whose short fiction I've enjoyed in the past, contributes "Stampede," about a single mom and her obnoxious brood and her attempts to raise them right. Realism to spare, sure, but wow those kids suck.

Two of my least favorite '80s horror writers, F. Paul Wilson and Richard Laymon, join the rodeo but get bucked off. Respectively, "The Tenth Toe" and "Dinker's Pond" aren't as bad as some works I've read by these guys, but they're both flat and immature, corny and obvious. Several names were new to me, even for a almost-30-year-old anthology: Lenore Carroll, whose "Eldon's Penitente," with its theme of pain, suffering, loss, and guilt, is rather memorable; and Robert Petitt, who swipes Lansdale's title and uses it all-too-literally in an SF tale.

Science fiction features in Al Sarrantonio's "Trail of the Chromium Bandits" and Gary Raisor's "Empty Places." Neither did anything for me, although the latter's mawkishness struck me as particularly lame and derivative of both Lansdale and Ray Bradbury. Neal Barrett Jr's tale of a Native criminal "Tony Red Dog" reads like Elmore Leonard-lite when it is readable at all, which it isn't mostly thanks to a constant barrage of character first and last names. Howard Waldrop's metafictional academic treatise on Western movies, "The Passing of the Western," strains even the most patient reader with its faux film history. God it was a grind getting through these stories.

The final three tales offer some surprises. Lansdale's own story, "The Job," is a mean little bugger with a nasty twist, a pre-Tarantino riff about two articulate killers and their unexpected target. I hope you like racist slurs, though. Richard Christian Matheson offers "I'm Always Here," with his usual pared-down prose, utilized here to solid effect in a story about a dying country singer in the Hank Williams mold finds a new lease on life. It's way better than most of the stories in Matheson's Scars. And for the finale, there's Chet Williamson and his too-cutely titled "'Yore Skin's Jes's So Soft 'n Purty...'" Man, there's a horrific climax waiting for you here.

That "cowpunk" novelty can't sustain an entire anthology, and the few tales here that I kind of enjoyed aren't essential reads by any means. I know every author has more and better work elsewhere; head out on the trail searching for those doggies, and let Razored Saddles fade into the sunset.

Lansdale and McCammon, c. 1990

Another of Robert McCammon's pleasant, inoffensive horror tales, "Black Boots," begins the anthology. A cowboy is being followed across the desert by a gunslinger wearing the titular objects. He stops in a dusty small "town" to drink some watered-down whiskey but soon sees "Black Boots" at the door of the saloon. Ironic tragedy follows. Its touches of surrealism are well-noted, but McCammon's simplistic style neuters the creepiness and final twist.

"Thirteen Days of Glory" by Scott A. Cupp upends a famous Western showdown with a decidedly transgressive aspect. Freedom must be for everyone or for none at all. Not bad, rather daring, probably offensive to some and liberating for others. Cupp's story is engaging and yet sad, one of the few here that are memorable.

"Gold" by Lewis Shiner is strong, well-told, tinged by magic-realism (a style much favored by genre writerly-writers), set in Creole swamps with strong characterization, but it ends with a damp whimper as it goes into mind-numbing financial details. A huge letdown.

Pulphouse Paperbacks, 1991, art by Doug Herring

David J. Schow's "Sedalia" is just... weird. Not fun weird, not weird weird, but just kinda what? weird, a proto-bizarro tale of ghost dinosaurs, maybe some kind of fossil fuel metaphor. Taking its title from the old-as-dinosaurs TV show "Rawhide," we've got "drovers" herding those ghost dinos in some future Los Angeles. It's marred by juvenile talk of dinosaur poop and incomprehensible politics, although I appreciated the fact that characters refuse to call a brontosaurus an apatosaurus as it "seemed too-too." 2015 showed that was correct.

Introduced by the editors as a bit of "Weird Tales" or EC Comics, Ardath Mayhar's "Trapline" is precisely that: a fur-trapper and a gory comeuppance. Sure, why not, whatever. The late Melissa Mia Hall, whose short fiction I've enjoyed in the past, contributes "Stampede," about a single mom and her obnoxious brood and her attempts to raise them right. Realism to spare, sure, but wow those kids suck.

Dark Harvest 1989 hardcover, art by Rick Araluce

Two of my least favorite '80s horror writers, F. Paul Wilson and Richard Laymon, join the rodeo but get bucked off. Respectively, "The Tenth Toe" and "Dinker's Pond" aren't as bad as some works I've read by these guys, but they're both flat and immature, corny and obvious. Several names were new to me, even for a almost-30-year-old anthology: Lenore Carroll, whose "Eldon's Penitente," with its theme of pain, suffering, loss, and guilt, is rather memorable; and Robert Petitt, who swipes Lansdale's title and uses it all-too-literally in an SF tale.

Science fiction features in Al Sarrantonio's "Trail of the Chromium Bandits" and Gary Raisor's "Empty Places." Neither did anything for me, although the latter's mawkishness struck me as particularly lame and derivative of both Lansdale and Ray Bradbury. Neal Barrett Jr's tale of a Native criminal "Tony Red Dog" reads like Elmore Leonard-lite when it is readable at all, which it isn't mostly thanks to a constant barrage of character first and last names. Howard Waldrop's metafictional academic treatise on Western movies, "The Passing of the Western," strains even the most patient reader with its faux film history. God it was a grind getting through these stories.

The final three tales offer some surprises. Lansdale's own story, "The Job," is a mean little bugger with a nasty twist, a pre-Tarantino riff about two articulate killers and their unexpected target. I hope you like racist slurs, though. Richard Christian Matheson offers "I'm Always Here," with his usual pared-down prose, utilized here to solid effect in a story about a dying country singer in the Hank Williams mold finds a new lease on life. It's way better than most of the stories in Matheson's Scars. And for the finale, there's Chet Williamson and his too-cutely titled "'Yore Skin's Jes's So Soft 'n Purty...'" Man, there's a horrific climax waiting for you here.

That "cowpunk" novelty can't sustain an entire anthology, and the few tales here that I kind of enjoyed aren't essential reads by any means. I know every author has more and better work elsewhere; head out on the trail searching for those doggies, and let Razored Saddles fade into the sunset.

Wednesday, July 15, 2015

Borderlands 2, ed. by Thomas F. Monteleone (1991): It's a Long Way Back from Hell

"The stories which follow don't have to be read on a dark night, with glowing embers banked in the fireplace, and a dark wind howling across the moors. You can read these tales under the clear light of day and pure reason... None of the tired old symbols which have defined the genre for far too long will be found here."

Editor Thomas F. Monteleone, introduction

How could any editor put together such a trailblazing anthology as 1990's Borderlands and not desire to follow it up with another volume? Again, Monteleone has gathered together stories by writers both (in)famous and not, stories that don't fit comfortably under the generic rubric of "horror," or any other either. Borderlands 2 (Avon Books, Dec 1991) treads a dangerous line: in its efforts to present horror/dark fantasy/suspense/science fiction stories that fit no mold it risks pretension, ambition outstripping execution (Prime Evil, anyone?); stay too close to identifiable territories and it is simply another paperback horror anthology cluttering up the shelves. The original Borderlands is one of my top favorites ever precisely because it tight-roped that line perfectly. Can Monteleone (pic below) and cohorts do it again?

For the most part, yes.

Disturbing is a word I'd use to describe the fictions herein; disturbing, unsettling, poignant, grotesque. Horror is normalized; lived with, understood as a fact of life, and isn't really scary anymore. Here there are moments struck in which I felt my flesh turn inside out, my shoulders shivering with revulsion, while my brain was engaged by a story's central idea, or an image or an implication. A writer who can do that to me—delight my mind while revolting my body—will have my undying devotion. And the story here that completely knocked me out, kept me glued to the page with a well-told tale and imagery of primal horror, was "Breeding Ground," by a man named Francis J. Matozzo.

I doubt you know that name. He had a story in the original Borderlands, "On the Nightmare Express," which was kinda cool. In this one he details three seemingly disparate events: a man undergoing surgery for excruciating craniofacial pain, an amateur archaeological expedition, a woman estranged from her husband. It's how Matozzo fractures the story and then pieces it back together, building suspense, that really won me over. Also, I dig evolutionary biology and that figures in here too, both literally and as analogy. Skin-crawlingly disgusting and sadly effective, "Breeding Ground" succeeds at all levels.

Another strong work is Ian McDowell's "Saturn," which is not a reference to the planet but to the Roman god who, well, devours his children. It is filled with grim wit and ends on one of the darkest notes in the anthology. Yes, I killed Michael. And buried his head, hands, feet, and bones in the geranium bed, after eating the rest. I can't even honestly say I regret it, although I'm sorry you have to find out.

One of the longest stories is "Churches of Desire" by the late Philip Nutman (pictured above at an archaic contraption known as, I think, "typewriter"). Clearly inspired by Clive Barker, a film journalist wanders through Rome, marveling at its filthy wonders and trying to pick up young men for anonymous trysts when he's not futilely attempting to interview an aging exploitation filmmaker. The "church of desire" is a porno theater, of course, and our protagonist eventually succumbs to its offerings, a depraved celluloid vision that would make Pasolini blush. While it may be too beholden to Barker, especially in its final paragraphs, "Churches of Desire" satisfies. The Church would welcome fresh converts that night and there would be new films to watch, new stories to tell, his own among them. In the name of the Father and the Son the congregation would sing silent praises to the Gods of Flesh and Fluids.

Sexual politics are a prominent feature in Borderlands 2, as the culture at large was beginning to deal with them in the early 1990s. The lead-off story, from F. Paul Wilson (of whom I am no fan) is "Foet," a so-so satire of high fashion and the absurd lengths to which people go in order to be stylish. You can probably guess the gimmick from the title. As with his notorious "Buckets," I found the approach over-done and the effect reactionary, which mitigates the shock factor. Better: "Androgyny," by Brian Hodge (pictured above), a sympathetic and relevant fantasy about a marginalized people, while Joe Lansdale's "Love Doll: A Fable" is an unsympathetic portrayal of someone who enjoys marginalizing those less fortunate, or simply those not born straight white blue-collar male.

"Dead Issue," from Slob author Rex Miller, doesn't have enough moral weight to justify its graphic sexual violence. Pass. "Sarah, Unbound," from which the Avon paperback chose its cover image, is Kim Antieau's solid contribution about a woman exorcising her real-life demons (She hated him so much. She had loved him. Why had he done it?) by counseling an imaginative yet abused child.

Borderlands Press hardcover, Oct 1991, Rick Lieder cover art

David B. Silva, the late editor of Horror Show magazine, returns to Borderlands with the final story, "Slipping." Like his award-winning "The Calling," "Slipping" is about real-life fears: in the former it was cancer, here it is aging. A hard-working ad man finds moments of his life disappearing from his memory, hours, then days. One moment he's at work, the next he's on the phone with his ex-wife, then he's having lunch with a colleague, with no conscious memory of how he got to any of those points. Silva makes the reader feel the terrible incomprehension of being aware of that incomprehension... but being powerless to stop it. Excellent. The physical distress of aging also appears in Lois Tilton's "The Chrysalis"; a character's dawning horror at its climax was a favorite moment of mine.

Children are horrible, aren't they? A classic horror trope. Facing the sins of our past, our guilt unassuaged by time or deed, is central to Paul F. Olson's "Down the Valley Wild," a sensitive, painful rumination on a childhood 40 years gone. It also contains some well-rendered moments of shock; overall it was a highlight of the book for me. "Taking Care of Michael" is only a page and a half long but J.L. Comeau's prose cuts deep and ugly, presenting madness under the guise of innocence.

White Wolf reprint, Oct 1994, Dave McKean cover art

All that said, Borderlands 2 also includes a handful of stories I found middling, so this volume doesn't quite reach the heights of its predecessor. These stories—"The Potato" by Bentley Little, "For Their Wives Are Mute" by Wayne Allen Sallee, "Apathetic Flesh" by Darren O. Godfrey, "Stigmata" by Gary Raisor—have their peculiarities, their moments of squick and dread, sure, but lack a certain edge to really sledgehammer the reader. Of course mileage may vary; other than Rex Miller's story none of them outright suck, and I think most readers will find much of Borderlands 2 to be an excellent usage of their time. Monteleone wisely continued the series for several more volumes, most of which I read as they were published through the mid-'90s—I clearly recall buying this one upon publication, eager and excited to delve into "steaming, stygian pools of unthinkable depravity"—and I hope to own them all again one day soon. Rest assured that all my future trips to "uncharted realms of bloodcurdling horror" will be documented and presented here, trespassing be damned.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)