There was a rattling, gagging sound from the girl, and they turned to watch in pity and loathing as she retched violently, her body curling in spasms, her fingers and toes clenched, her gaping mouth spewing jet after jet of reeking substance that covered her and splattered the wall and ran sluggishly in long viscous tendrils down to the floor.

A young teenage girl in unbearable torment of unknown origin. Her beleaguered parent. Two priests with competing ideas about their belief in God and Satan. A harrowing test of wills against a force the modern world has forgotten...

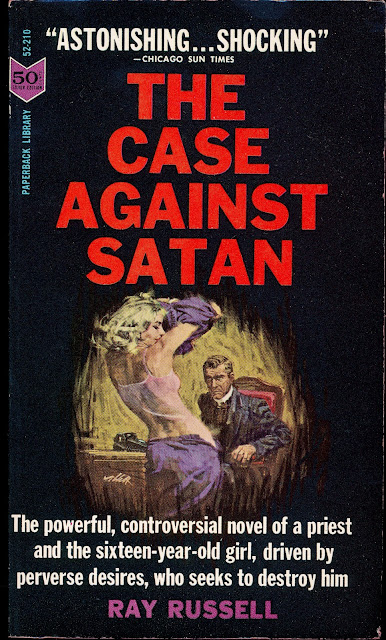

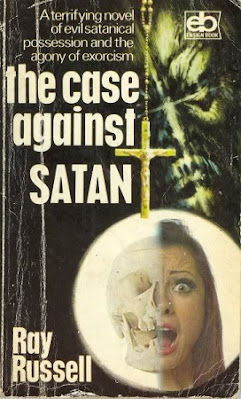

Modern horror would be a poorer thing were it not for the book and film The Exorcist—that's not an overstatement. William Peter Blatty's thrilling, chilling tale of innocence soiled and faith tested, of doubt, guilt, and ultimately of sacrifice, has touched the popular horror imagination at that same primal archetypal level as Dracula and Frankenstein. But as it was with those two monstrous icons, The Exorcist also had its own forgotten precursor. I'm talking about the 1962 novel The Case Against Satan, by the late great Ray Russell (1924-1999, seen below in an undated photo, but probably late Sixties or so).

You may recall I've written positive reviews of several of Russell's works over the years, I'm absolutely a fan, happy to see all his horror Gothics back in print today. His adeptness at combining a dark, literate sophistication with "distasteful" genre elements, which might seem beneath his skill set, is admirable. Grand Guignol bloodiness in works like "Sardonicus" and Incubus is polished by his steady pen in prose both accessible and lively, often delivered with an ironic tone, a devilish wink. As editor for Playboy magazine in its early days, he no doubt sharpened that pen and that penchant for macabre philosophy when working with writers like Ray Bradbury, Charles Beaumont, Kurt Vonnegut, and others of that sensibility.Russell's dialectic in his genre fiction, and first seen in this novel, is one of superstition versus rationality, of tradition versus modernity, of enlightenment versus religion, as one reviewer of Case Against Satan notes. Indeed, this kind of against-the-grain approach was also part and parcel of the Playboy "philosophy," if you will: unshackling our minds (and bodies!) from the strictures of the past, strictures too often rooted in myth and superstition (i.e., religion). From such conflict does Russell approach demonic possession in the modern world. And no surprise that sex is suspected at the root of the "possessed" girl's problem: repressed sex, of course, a great raw force that seethed and snarled for release.

As tête-à-têtes go, here Russell is in the "both sides" camp, a final answer which Russell leaves open-ended. The first chapter is titled "The Two Sides of Midnight"—indeed, all the chapter titles seem to predict black metal songs!—and that gets right at Russell's views about the difficulty we have perceiving even what we see right in front of us. "The Hand of God is quicker than the eye," as one character quotes.

Russell combs through history and literature to find some delicious, torturous horrors, as is his wont, easy enough to do with the Catholic Church. Intellectual talk between the two conflicting priests, Father Halloran and Father Sargent, when they're not actually exorcising poor young Susan Garth is stimulating; the cranky teetotaling anti-Catholic John Talbot was a hoot, with his scandalous insight that the Church and communism are opposed to one another solely because they are both totalitarian... Total power, total control. Control over everything—over the body, over the mind.

Compact and tightly-wound at around 150 pages, Case is deceptively simple, but still dramatic and lurid at times; like The Exorcist it is not

necessarily a novel of horror but one about belief, doubt, conviction, redemption, but are these antiquated ideas in the 20th century? The concept of God and Diabolous struggling for the human soul is accepted only if it is translated into Freudian jargon—the superego and the id struggling for human reason.

I can’t say for sure but it seems like, for all the similarities, that Blatty took Russell's book and blew it up to bestselling mass-appeal status. Case does not have the scorching vulgarisms, the relentless throb, that all-hell-breaks-loose energy that kept millions upon millions of Exorcist readers turning pages and unable to sleep. Its dry-as-dust title perhaps an inkling to what's inside, Case didn't wow me like Russell's other works; he always has his characters talk a lot but the theological discourses here can wear on the reader.

Yet the author's intelligence, subtlety, and psychological astuteness can make up for some of the drier sections, as he uses a sensational topic to illuminate the darker regions of the human mind. Ray Russell is the kind of just-maybe-smarter-than you pal you enjoy talking with over a bottle of good booze late into the darkening night... but just maybe you've heard this particular story before.

But have any of you ever heard and wondered at strange sounds in Catholic rectories? In the Unholy Hours, past the witching time of night, have you ever heard sounds that seem like the screams of poor girls in mortal agony? Have you ignored them? How long will your conscience let you ignore them?