In 1993, in my early 20s, I was working in a giant chain bookstore known as BookStar in Cary, NC. It was basically a Barnes and Noble (who eventually bought, rearranged, and then closed down the store), guys had to wear ties and dress pants, like it was fucking church. Several of my coworkers were horror fiction fans, both of the modern and classic variety, and we wasted many a working hour talking about the genre while ignoring our shelving duties. At this time the horror mass-market paperback boom was beginning its downhill swing, although I well recall the publication of many a serious title around then: Animals by John Skipp & Craig Spector, Lost Souls by Poppy Z. Brite, After Age by Yvonne Navarro, Skin by Kathe Koja, Grimscribe by Thomas Ligotti, The Golden by Lucius Shepard, as well as the continuing, final titles from the Dell/Abyss line. And in June came Wet Work, published by Jove Books, the first novel from young British author and journalist Philip Nutman.

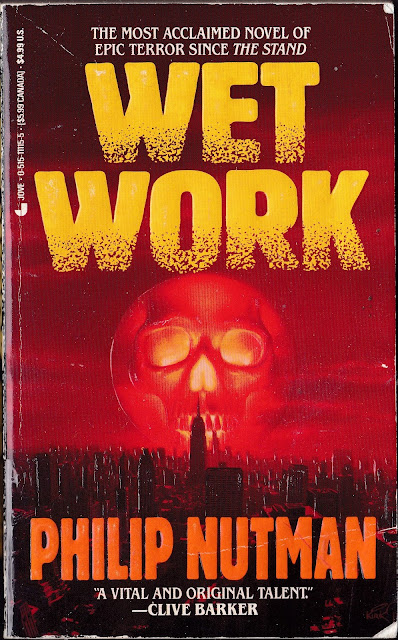

I already knew the author's name from various Fangoria articles as well as a few of his short stories. They were good, smart, effective, and I remember shelving fresh new copies of Wet Work and thinking it might be worth a read. The critical blurbs came not from, you know, the newspaper reviewers but from fellow horror scribes like Clive Barker, Kathe Koja, Douglas E. Winter, Nancy A. Collins, Skipp n' Spector themselves, and Stephen King as well (although we've learned how unreliable a King quote can be). All a good sign to me!

I already knew the author's name from various Fangoria articles as well as a few of his short stories. They were good, smart, effective, and I remember shelving fresh new copies of Wet Work and thinking it might be worth a read. The critical blurbs came not from, you know, the newspaper reviewers but from fellow horror scribes like Clive Barker, Kathe Koja, Douglas E. Winter, Nancy A. Collins, Skipp n' Spector themselves, and Stephen King as well (although we've learned how unreliable a King quote can be). All a good sign to me!

And yet—I didn't read it. My taste for the genre was waning some; sure, I was rereading some favorites but not really keeping up any longer. Like I said, I could tell the boom was slowing down, despite some interesting works arriving. This was when I was getting into my hardboiled/crime/noir phase, James Ellroy, Jim Thompson, Woolrich, Cain, Chandler, James Lee Burke. Tastes change, you gotta go where your heart leads you.

So when I finally got around to Wet Work last week, I wasn't sure if it was gonna read like a last gasp or a fresh breath. Turns out, it was neither, and it didn't need to be: it's simply a briskly-told horror novel of a zombie apocalypse. Ignore the "epic terror" comparison to The Stand on the cover; compared to King's mammoth-sized tome, Wet Work is a wee little rodent, scurrying about busily while getting the job done in a fraction of the pages. It's radiation from a comet that sets things off, akin to the space probe origins of the zombies in the original Night of the Living Dead. Sections of the first half resemble the early parts of the 1978 Dawn of the Dead, although these characters don't know yet that they're dealing with the undead. All this is no ripoff or plagiarism, however: Wet Work is an expansion of a Nutman short story of the same name, and it was first published in 1989 in the essential undead anthology Book of the Dead, borne upon us by Skipp n' Spector. A major work of the splatterpunk movement, it featured stories all written in the ghoulish universe of Romero's (then-) trilogy of zombie horror movie classicks.

2005 reprint by Overlook Connection Press

Any consumer of popular entertainment, horror or not, will be right at home in the familiar environs of Nutman's various characters and settings: secret military assassins, rookie cops, seasoned cynical cops, adults with dying parents, the lovelorn, the alcoholic, the teenage dirtbag, the cheating rich, the drug dealer, the junkie, DC/NYC, the airport, the strip club, the lab, the White House. Nothing to criticize, really; Nutman fills in color and detail no matter where he's describing. It's all as immediate as any movie or TV show, slick but not shallow, but not overladen with heavy meaning or a desire to upend tradition. His prose is lean, cynical, our tale starting off with the whitehotwhiteheat italics and ...ellipses... so beloved of the splatterpunks, what better way to get to the meat of the matter?

Skipping in well-played rhythms, Nutman shuffles his plotlines well, not lingering too long on any one locale. This is a skill I wish more horror writers had mastered: the thrust of narrative, the propulsion of story, the ability to convey movement in time forward while invoking a sense of impending doom overall. Nutman's background as a film historian has to account for his crisp, capable hand at this task, as the novel is cinematic as hell. Horror violence and gunplay action mingle here expertly.

Overall Wet Work is a short sharp shock of splat fiction, never dwelling too long on any character(s), moving at a brisk pace as the end of the world approaches. Not that the story is shallow or insipid, it's just that Nutman knows that we know how the story goes, and isn't trying to reinvent the wheel. His fresh take on zombie myth isn't exactly mind-blowing, but it is interesting enough to keep even a seasoned horror fic fan reading to the bleak, downbeat ending. Who'd want it any other way?

+Cover+Kirk+Reinert.jpg)