Tuesday, September 2, 2025

RIP Chelsea Quinn Yarbro (1942 - 2025)

Saturday, February 15, 2025

Under the Fang, edited by Robert McCammon (1991): The World is a Vampire

Nothing, it seems, or very little, to save ourselves. Thus is the setup for the stories in Under the Fang (Pocket Books, Aug 1991, cover by Mitzura), under the auspices of the Horror Writers of America coalition, with editing duties by iconic bestselling paperback author Robert R. McCammon. Akin to the zombie apocalypse anthos based on George Romero's movies, Book of the Dead (1989) and Still Dead (1992), (which of course hearken back to 1957's I Am Legend) all the stories exist in this new world, with each author bringing their own special methods of madness to the proceedings.

Virtually all the vampire anthologies published prior to the early

Nineties were collections of classic stories, moldy golden oldies by the

likes of Bram Stoker, Polidori, EF Benson, Crawford, Derleth, et al.

Esteemed editor Ellen Datlow gave us Blood is Not Enough in 1989 and A Whisper of Blood

in 1991, which featured all-new vampiric works by the cream of the

genre's crop. I'll confess: I've read neither, even though I've owned

them since Kurt Cobain was still alive. But those two volumes seem to be

the first that showed that the old symbols and themes of vampire

fictions could be given fresh new life at the end of the century.

They've won. They come in the night, to the towns and cities. Like a slow, insidious virus they spread from house to house, building to building, from graveyard to bedroom and cellar to boardroom. They won, while the world struggled with governments and terrorists and the siren song of business. They won, while we weren't looking...

He handily sketches out the scope of the situation in a couple pages, setting us up for the tales to come. Second is his story "The Miracle Mile," of a family's drive to an abandoned season vacation spot and amusement park. Vampires have of course overrun it, and Dad is pissed. With his signature mix of corny sap and derivative horror, McCammon delivers perfectly cromulent reading material. It's just that I always find him square and dull and earnest, and not my jam whatsoever.

The recently-late Al Sarrantonio's "Red Eve" is an effective slice of dark, poetic fantasy in full Bradbury mode, which was common for him. I have no idea who Clint Collins is, but his brief "Stoker's

Mistress" is a high-toned yet effective bit of metafiction about

vampires "allowing" Bram Stoker to write his "ludicrous" novel Dracula... Shades of soon-to-be-unleashed Anno Dracula. Nancy A. Collins had already had her way with the vampires;

"Dancing Nitely" is a perfect encapsulation of the modern image of the

unholy creature: they all want to live in an MTV video scripted by Bret

Easton Ellis. Contains scenes of NYC yuppies dancing under blood spray

at an ultra-hip underground vamp bar, called Club Vlad, with a neon

Lugosi lighting up its exterior. We may cringe looking back at it today,

but back then this style was au courant du jour.

Late crime novelist Ed Gorman delivers an emotional wallop in "Duty," powerfully effective even though I was half-expecting how the turnaround was going to happen. I gotta try one of his full horror novels! Richard Laymon

does his his usual schtick of adolescent ogling and rape fantasy

scenarios rife with toxic masculinity in "Special," this story ends on an unexpected

note of enlightenment. Better than other things I've read by him, but not enough to make me a fan.

Together, Chelsea Quinn Yarbro and Suzy McKee Charnas pit their own fictional vamps—Count St. Germain and Dr. Edward Weyland, respectively—against one another in "Advocates," the most philosophically ambitious work here; no surprise, as both women approached the vampire as a concept in their other writings. Could've been better I felt, less than the sum of its parts.

On to the finest stories within: my favorite was Brian Hodge's

"Midnight Sun," which is so well-conceived in scope and execution I

daresay he could've written an entire novel using his scenario. Muscular and convincing, its setting of a military outpost in frozen wastes makes it a standout; the conflict, not only between humans and vampires but also between vampires themselves give the story a real moral heft. A close second was "Calm Sea and Prosperous Voyage," by Chet Williamson, in which a loving husband and wife experience tragedy and woe after escaping into a cabin in the woods. Tough, moving, unsettling stuff.

Other stories here, by authors both known and unknown, run up and down the scale from ok sure fine to oh well whatever nevermind. This might not be the best antho of the era I've ever read, but the quality of prose is very high—this was the HWA, after all—even if the story itself doesn't quite succeed. Me, I could've done with some more graphic bloodshed/drinking, or classic Lugosi/Lee-style vamp action in the good old Les Daniels' tradition. No matter; your mileage may vary as well (PorPor Books enjoyed it maybe a smidgen more than I did). Overall, I'd say Under the Fang is an easy recommendation for your horror anthology and/or vampire fiction shelves.

Friday, May 17, 2024

The Night Creature by Brian N. Ball (1974): She Rides

Fortunately it is the case for this 1974 novel The Night Creature (published in the UK as The Venomous Serpent), by British scribe Brian (N.) Ball. For several weeks I meandered through the first two-thirds of it. Not because it was bad, or uninteresting; Ball, a prolific writer of SF, is a capable author, if kinda dry (it's told in first person, a style I've found myself losing interest in over the years). No, I just found it all rather tame and indistinct; for every little aspect that made me perk up, I'd have another several pages of, sure, okay, whatever. The book would sit on my nightstand for days untouched, till last week. Dammit, I can finish this guy! Spurred on by a few positive reviews on Goodreads, I sat down early one afternoon determined to get to the end. And I did! And boy was I glad!

And thus follows standard procedure: Andy convincing Sally what he's seen, a visit to the ruined church where Sally first made the rubbing, learning the local lore of the people in said rubbing, intimidating locals warning them off the church property, cranky coppers (I was fool enough to call on our local policeman), and one truly old eccentric priest Andy tries to enlist in his aid when Sally disappears one day. The lady Andy seeks is one of the blood-drinking living dead: Undead, blood-crazed, monstrous thing from the tomb she might be, there was no doubting her beauty. Can he rescue Sally in time from the Lady Sybil?

Not unlike a contemporaneous Hammer horror film, The Night Creature is a mere wisp of a book at barely 150 pages. It truly does ramp up suspense and interest in the last third, so by the end, the tale has found that sweet spot, the one I personally truly adore and crave, and nuzzles there, suckling and secure.

Friday, January 21, 2022

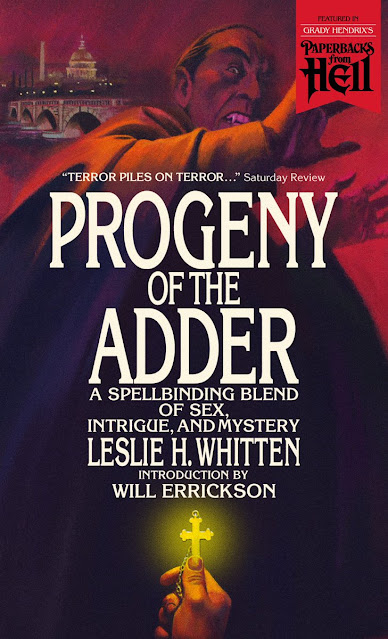

Latest Title in Valancourt's Paperbacks from Hell Series: Progeny of the Adder!

Thursday, October 29, 2020

Favorite Horror Stories: "Shambleau" by Catherine L. Moore (1933)

Featuring a semi-heroic character that Moore would use again and again named Northwest Smith, "Shambleau" at first comes across as standard pulp for its day: Smith is a space pilot, an outlaw, a smuggler, going about business in a kind of Wild West city called Lakkdarol, an outpost on Mars: a raw, red little town where anything might happen, and often did (Smith is obviously a precursor to Han Solo; this type of pulp adventure is just what George Lucas would repurpose for the Star Wars universe).

A wild mob is chasing down a berry-brown girl in a single tattered garment whose scarlet burnt the eyes with its brilliance. Smith draws his laser gun in defense of the poor creature as she evokes a kind of sympathy in him, even though he's no hero. He talks down the mob, who keep shouting "Shambleau!" The leader informs Smith "We never let those things live," but Smith informs him that Shambleau is his, he's keeping her. This puzzles and astonishes the crowd; as they disperse, the leader spits out at Smith: "Keep her then, but don't let her out in this town again!"Obviously relieved, this girl known only as Shambleau cannot speak much English, and Smith is perplexed by the bloodthirsty disgust the mob had evinced towards her. Their brief conversation is halting, but she manages to get out, "Some day I—speak to you—in my own language" (nice foreshadowing!). Smith knows he needs to get her someplace safe, like back to his sparse, rented room. As they walk, he notices others on the streets staring after him and the turban-headed alien girl in disbelief.

Back in his room, Smith tries to get the girl to eat, but she will not. He tells her she can stay safe here, and he goes out to do his business: Smith's errand in Lakkdarol, like most of his errands, is better not spoken of. Man lives as he must, and Smith's living was a perilous affair outside the law and ruled by the ray-gun. He returns that evening, drunk on “segir,” or Martian booze, and is surprised to see Shambleau still there. Yes, he's drunk... and suddenly horny. They embrace...Her velvety arms closed around his neck. And then he was looking down into her face, very near, and the green animal eyes met his with the pulsing pupils and the flicker of—something—deep behind their shallows—and through the rising clamor of his blood, even as he stooped his lips to hers, Smith felt something deep within him shudder away—inexplicable, instinctive, revolted. What it might be he had no words to tell, but the very touch of her was suddenly loathsome—

a lock of scarlet hair fell below the binding leather, hair as scarlet as her garment, as unhumanly red as her eyes were unhumanly green. He stared, and shook his head dizzily and stared again, for it seemed to him that the thick lock of crimson had moved, squirmed of itself against her cheek.

Smith blames this "squirming" on too much too drink, tells the girl to sleep in the corner, and then gets into bed, where he dreams strange dreams beneath a dark Martian night, of some nameless, unthinkable thing ... was coiled about his throat . . . something like a soft snake, wet and warm, sent little thrills of delight through every nerve and fiber of him, a perilous delight. He is like marble, rigid, unable to move, fighting against it, till oblivion takes him and then, bright morning. Dismissing this “devil of a dream,” he tells Shambleau she can stay again, but he'll be leaving Lakkdoral in a day and after that, she'll be on her own.

It was not until late evening, when he turned homeward again, that the thought of the brown girl in his room took definite shape in his mind, though it had been lurking there, formless and submerged, all day. "Formless and submerged," you say? Freud would, as it's said, have had a field day. Shambleau still has not eaten, still speaks in halting English obscurities like "I shall—eat. Before long—I shall—feed. Have no worry." Smith brilliantly asks her if she lives off blood, and she scoffs: "You think me—vampire, eh? No—I am Shambleau!" Well, that clears things up.

That night brings a fuller realization of the horror that is Shambleau, and Moore spares nothing in her efforts to reveal what a danger to the rational human this alien is. Smith wakes to see Shambleau teasing him as she undoes her turban, allowing those scarlet locks to writhe and glisten in an obscene tangle, drawing Smith in helplessly. It's as if he recognizes what she is...

And Smith knew that he looked upon Medusa. The knowledge of that—the realization of vast backgrounds reaching into misted history—shook him out of his frozen horror for a moment, and in that moment he met her eyes again, smiling, green as glass in the moonlight, half hooded under drooping lids. Through the twisting scarlet she held out her arms. And there was something soul-shakingly desirable about her, so that all the blood surged to his head suddenly and he stumbled to his feet like a sleeper in a dream as she swayed toward him, infinitely graceful, infinitely sweet in her cloak of living horror.

Jayem Wilcox’s illustration for Weird Tales

Moore goes on in this amazing pulp fashion, overheated prose all silken seductive slidings, wet and glistening tentacle tresses like serpents, eager and hungry as they crawl towards this man frozen in fear... and desire. As she embraces him, she murmurs, "I shall—speak to you now—in my own tongue—oh, beloved!" Whew. Smith is bewitched, nearly hypnotized, a drug addict now, his identity subsumed into the hungering that Shambleau is, welcoming mindless, deadly bliss.

this mingling of rapture and revulsion all took place in the flashing of a moment while the scarlet worms coiled and crawled upon him, sending deep, obscene tremors of that infinite pleasure into, every atom that made up Smith. And he could not stir in that slimy ecstatic embrace—and a weakness was flooding that grew deeper after each succeeding wave of intense delight, and the traitor in his soul strengthened and drowned out the revulsion—and something within him ceased to struggle as he sank wholly into a blazing darkness that was oblivion to all else but that devouring rapture.

Like the femme fatale of a noir story, Shambleau promises heaven but delivers hell. Only the arrival of a space-pal named Yarol saves Smith; Yarol engages in a last-minute feat of derring-do, as he recognizes the alien for what it is, recalling in him ancient swamp-born memories from Venusian ancestors far away and long ago. Moore concludes her wild tale with the two space friends discussing the origins of Earth myths, an alien race, half-forgotten legends, a race older than man... you know the stuff! Yarol insists that if Smith ever sees a Shambleau again, "You'll draw your gun and burn it to hell."

While horror as a genre is so often concerned with revulsion, fear, despair, and the like, Moore seemed to be clued-in to the uncomfortable fact that horror also can explore forbidden, attractive, addictive desires that polite society deem unacceptable. But as psychologists understand, desire and disgust are rarely opposites; they mingle, coalesce, to beckon us towards our doom... and we’d have it no other way.

Saturday, October 10, 2020

Favorite Horror Stories: "Blood Son" by Richard Matheson (1951)

Of course there was the time they found him undressing Olive Jones in an alley. And another time he was discovered dissecting a kitten on his bed.

How about that for a creepy kid? I mean, that is just textbook. Red flag and three-alarm fire. Get this kid into a psych ward posthaste. But in Richard Matheson's telling, "Those scandals were forgotten." I know it beggars the imagination today, but you know, as Lou Reed and the Velvet Underground sang, "Those were different times." And Matheson, one of the Founding Fathers of our beloved horror and dark fantasy genres, isn't writing a true-crime tale; this early Fifties, much-anthologized short story is called "Blood Son," and he's only setting the stage for our disturbed young protagonist to fulfill his much-desired destiny.

Originally appearing in a spring 1951 issue of a magazine called "Imagination" under the title "'Drink My Red Blood...'", Matheson uses spare, plain sentences in paragraph form to highlight the single-mindededness of little Jules: he wants to be a vampire. Born "on a night when winds uprooted trees" with three teeth to latch onto his mother's breast to drink mingled milk and blood, Jules has never not been creepy. He doesn't speak till he is five years old and then it's to say "Death" at the dinner table. Then he starts making up words, edgy freak-out-the-squares stuff like "killove" and "nighttouch." He's a failure in school, unless it's reading and writing, then "he was almost brilliant." A literate creep!When he's 12 he goes to the movies one Saturday and sees a picture called Dracula (Matheson doesn't have to specify which Dracula because in 1951 there was only one Dracula). And like many kids who see a movie that makes them feel something special but they aren't quite sure what to do with those feelings, he goes home and locks himself in the bathroom for two hours. Ignoring his parents pounding on the door, Jules finally emerges with "a satisfied look on his face." But he's also got a bandage on his thumb, so it's not that kind of creepy. I like this kid—he skips school to hang out at the library, and from there steals a book—ok, that's not so great—but it's Bram Stoker's Dracula so I dunno, I guess I like him again. Showing his brilliance, he reads the book straight through in the park, and then walks home reading it again "as he ran from street light to street light." As someone who tried to read the Stoker novel when in kindergarten, I really admire Jules: "As the days passed Jules read the story over and over. He never went to school.""'My Ambition' by Jules Dracula. When I grow up I want to be a vampire. I want to live forever and get even with everybody and make all the girls vampires."

Such laudable, ambitious, and clearly-articulated life goals. This kid is goin' places! But alas, he's dragged out of class and is in big trouble, mister.