"You're nothing! Oh pardon me... it's just that we were all so frightened... we made such a business out of you... I'm laughing as much at our own foolishness as at your regrettable lack of substance..."

—Glen Bateman, upon first meeting Randall Flagg

Let's get right to it, gang:

The Stand has never been one of my favorite

Stephen King novels. No need to get excited; I'm well aware of its status as maybe his most beloved book, if one may use that word for a novel about a plague that kills more than 99% of humanity. Despite its imposing length, it may be the one Stephen King novel people have read who've read only one Stephen King novel.

Doubleday hardcover, Oct 1978

Bosch-inspired art by John Cayea

But when I read it in 1987 or

'88, I found it lacked what I most loved about Stephen King; that is, an

intimacy, an atmosphere of the chummy detailing of the American

quotidian that he'd done so supremely well in his other novels and short stories. Reading King felt like

home, and

The Stand

most definitely did not feel like home. How could it? It is an epic story

about people who no longer have one and are desperate to build a new

one. That epic length never bothered me: I'd already read 1986's

IT as soon as

it was published in hardcover. But the giant panoramic post-apocalyptic

canvas really did not appeal to me, and while I read almost every other King

work over and over and over again,

The Stand was one and done for me

.

Stephen King in 1978

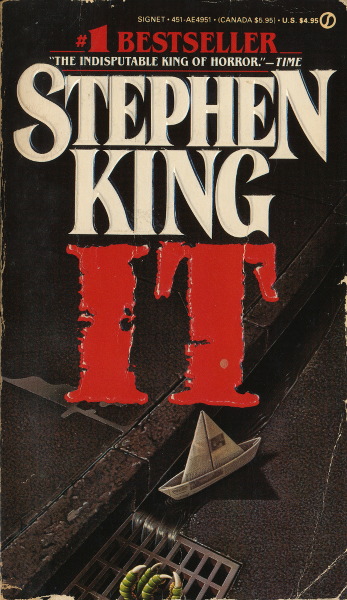

Most horror fiction fans probably have a decent understanding of the

book's publication history: Doubleday hardcover in '78, Signet paperback

in '80, then in 1990 another Doubleday hardcover edition in which King put back in

something like 500 pages from his original manuscript that he himself

had edited out before its first publication (

Complete & Uncut, this new edition said;

Uncircumcised would've

just been impolite). In case you don't know

the particulars, he spells them out in more detail in his intro to the

'90 edition. Going by online reviews, this expanded edition is either:

A) the best thing ever; B) the worst thing ever. Many prefer the shortened original. People have strong

opinions about Stephen King books, it may surprise you to learn, especially one regarded as his greatest. In fact, you're

about to read one now.

First Signet paperback, Jan 1980

Don Brautigam cover art

(Okay, friends and neighbors, before I forget, here there be

spoilers galore. I'm gonna be rambling all about

The Stand and you won't want to continue if you haven't read either version. But maybe come back after you have!)

Doubleday hardcover, May 1990

Working in a bookstore when this massive 1,200-pager arrived on

shelves, I was interested just enough to skim the new opening and

closing chapters. The opening is now the family that careens into

Hapscomb's Texaco at the beginning of the '78 version; it's fine, I

guess, starting off the story in a panic (They're all D-E-A-D down there). But I recall being particularly put off by the final

chapter, in which the evil, otherworldly Randall Flagg's time has come round again...

accompanied by a Bernie Wrightson illustration that's entirely too

comic-booky. It seemed all too obvious, weirdly unimaginative (but probably a way

to link the Gunslinger/Dark Tower series into it, which King was

now writing and Signet publishing in earnest). I was deeply

unmotivated to read this new leviathan, and remained so... till now.

I'd never seriously considered rereading

The Stand.

What a commitment! Perhaps it was something deep-seated in my

unconscious, who knows, guess that's why I can't even recall how I

picked it up at the beginning of December, because before I knew it was

knee-deep in that mother. Reading the 1980 Signet paperback—I'm happy to own a mint first-print of it, but I'm not a monster, I do have a beat-up copy for actual reading—I was

something like three or four hundred pages in and the story-line felt...

constrained. Uptight. Airless. Condensed. I began to think maybe there

was something to the idea of the complete uncut edition after all. Maybe

I did owe it to myself to bite the bullet, go for

broke,

ride the lightning, and dive in. So I put my reading on hold till I was able to

locate a nice, also first-print, sorta mint paperback (published in a sturdy mass market edition in May 1991) for a sawbuck, then

went back and started over a week or so later. Seriously. I did.

And I'm not gonna lie: it was a grind. King's well-known weakness

to overstuff his narratives with irrelevance and folksy analogies is on

full display. He went wide instead of deep, expanding but not layering. The problems with The Stand are more serious than simply the number of pages: the real fault lies in execution, in writing, in characterization, and in scenario. Neither the 1978 nor the 1990 version is exempt from these fatal flaws; the longer edition simply reveals these flaws as baked-in, that's all. King famously said back in the '80s that his books were the literary equivalent of a McDonald's meal, but that junk food's still gotta be fresh, hot, and correctly salted, right? Right.

Well-known and -loved characters like Stu Redman, Frannie Goldsmith,

Larry Underwood, Nick Andros, et al, all get extra sentences in their

personal histories, but nothing I found essential or particularly

enlightening. Better were the vignettes of superflu survivors who meet grisly ends, with King evincing both sympathy and merciless horror: a Catholic man whose family dies but won't commit suicide because it's a mortal sin; a child on its own falls down an improperly sealed well but does not die right away. Chilling, classic King... but mere crumbs.

Anchor Books, 2011

Also better and included now is one of King's patented family breakdown

scenes that's top-notch. Early on, pre-apocalypse, it's pregnant Frannie, our heroine, in an argument with her mother in the family's parlor drawing room, whose

hysteria over Fran's out-of-wedlock family way borders on the absurd. The confrontation crackles with real emotion, King getting at class and social standing and good breeding all at once. I hungered for more of

this kind of King Americana.

"How could you do something like this to your father and me?" she asked finally... "How could you do it?" she cried. "After all we've done for you, this is the thanks we get? For you to go out and... and... rut with a boy like a bitch in heat? You bad girl! You bad girl!"

New English Library, 1988 reprint

Trashcan Man, a pyromaniac gutter bum, with stupid

dancing and cries of "

Cibola," remains a tacky, tasteless character. And

then King unleashes, in the uncut, a dude known as The Kid, so now we've got Trashcan and the Kid (heeey!

don't tell me you forgot

that Saturday

morning teevee classic). It is a dopey read, a side travelogue no one asked

for, almost too King for King, if you know what I mean. "Kill your

darlings" goes the old writers' adage, and this darling should have

died, died, died. The Kid is a caricature of a King character, a parody.

While the Kid comes to disturbing end, he's cringe-inducing,

dressed like a greaser extra from, well,

Grease, spitting out embarrassing dialogue like

"Coors beer is the only beer, I'd piss Coors if I could, you believe that happy crappy, awhoooooga" then sprinkles in some Springsteen and Doors lyrics. Then he rapes Trashy with a pistol. You believe that happy crappy?

Despite the various gross, gruesome scenarios King revels in, there's a naivete I hadn't noticed on first

read. This depiction of the good folks of Boulder rebuilding society, all-American salt-of-the-earth

types, was just so

square. Why, they even have a ready-made town drunk and a hot-rodding teenager to contend with, and good god I was up to

here with old prof Glen Bateman's observations about "-ologies" not being enough anymore, the glad-handing and back-slapping, the jokes during their endless, oh god

endless meetings to figure out how to get busy being born all over again. Like everybody just up and knows

Robert's Rules of Order and has a perfect conception of deploying committees and subcommittees

and voting and vetoing and accepting in toto and everyone is happy to

vote for the main characters.

New English Library paperback, 1991

Speaking of characters, too many fade in and out under the weight of the expanded

narrative. Women are, in old-time pulp fashion, described in terms of

physical appearance. And the endless litanies of names! If one more

character said about another "Joey Shmoey, by name" I was gonna plotz.

"Sally Lovestuff,

her

name is," or "Goes by the name of Bigtop Ragamuffin, he does" or "Tall,

pretty girl, she is, that Wendy Jo" and "Heckuva nice guy, sounds like,

over this jerry-rigged CB contraption we got going on here." Their dialogue is irredeemably corny, as if virtually every character

was

being voiced by a cast of cracker barrel regulars. He's always populated his books with jes' folks types, but Jesus

everloving

Kee-rist, King, did everybody who survived the superflu just walk fresh off the set of "Hee Haw"?

I'd

forgotten deaf-mute Nick Andros was even around, and overshadowing him is a crime

as he's one of the novel's most sympathetic characters. His

sacrifice during Harold Lauder's bombing is one of the novel's high

points, maybe its most heartbreaking moment:

He couldn't talk, but suddenly he knew. He knew. It came from nowhere, from everywhere. There was something in the closet. Rereading it just now to get this quote right, hairs on my arms stood up. Nick's dream appearances to poor Tom Cullen, explaining how Tom has to try to save Stu Redman's life, are touching—if a little too convenient plot-wise.

French edition, 1981

Speaking

of Lauder, how's he for King's prescience about a certain type of

American male we see all too often these days? The creep, the outcast,

the psycho, the loner (today he's the incel, the school shooter, the

edgelord, the MRA, the dude who complains about "nice guys" and getting

"friendzoned," folks, these entitled losers are

nothing new). Nadine

Cross's unholy seduction of him for Randall Flagg is disgusting, sad, and all

too successful (she lets him fuck her in the ass but not in the pussy,

saying that will keep them pure for Flagg, my goodness what a lovely couple

those two make). Harold's suicide after the bombing sticks in the

throat—men like him shouldn't get free of the consequences of their

actions so easily, even if they do express remorse as he does in a suicide note.

Later '90s reprint

Let's just say it: for all his storytelling prowess, King can be a

lazy writer. Much of the novel I read on autopilot; for as long and weighty

the book is, it's easy—too easy—to read. Complexity, density, ambiguity is out; useless puffery and bloat is in. I skimmed pages because King was repeating himself, describing

things I already knew: someone grimacing, people gossiping, everybody walking every goddamn place, Stu calling

Glen "baldy," Flagg grinning, Fannie crying, I mean

sweet Jesus Fran crying. He uses simple phrases over and over, engages in sophomoric philosophizing, his details about character

behavior ring false: I lost count how times someone

laughs till tears stream down their cheeks, uses

someone's name more than once in a conversation, is described as being "naked except for shorts" (i.e., not naked), etc. And how much do you

like reading about car-crash pileups? There are more of those here than

in a J.G. Ballard novel. Where was everybody

going?

And where's the mass breakdown of society? That's what I felt the '78

edition was lacking, why the story felt abbreviated. I expected more in

the complete edition, but King takes the easy way out. Rather than do

the heavy lifting of imagining and describing the political and social

fallout as the world's population succumbs to a man-made

disease, King presents his scenario as

fait accompli. There's more of the military scientists realizing the enormous

oopsie they've done and their futile attempts to fix it, which I liked

as it was precisely the kind of approach I felt was missing from the

'78 edition. I can't help but think this

was a huge miscalculation, leaving out the nitty-gritty of not only

world-building, but world-destroying. I needed a bigger bang, not this

whimper. Ironic to say this about a 1,200-page novel, but I wanted

more.

Later Signet reprint with iconic Eighties typeface

It's all too easy today to see the creaky underpinnings

and cracks in the foundation of King's scenario. Again, I needed more

social apocalypse. If you're gonna have superflu-sick black

soldiers dressed like pirates take over a TV station

and begin to execute white soldiers on live broadcast television, you

better bring some wit, irony, or satire to the proceedings; just

slapping it down bald-faced on the page makes you seem oblivious to the

racist tropes you're invoking... or maybe not even oblivious. It's

dangerous ground, and if you're gonna tread on it, know what you're

doing. Have a bigger, more audacious plan. Reveal the racism, the

sexism, the classism and all the other -isms that permeate American

society, that have festered and eaten us from within, and which now have

exploded in the advent of the end of the world.

Speaking

of racism, what of Mother Abagail Freemantle, the century-old black

woman who is the locus of the survivors' dreams and visions, a wizened,

hearty Christian woman of the Midwest who knows well the time is nigh

and perhaps the Lord in all His infinite wisdom and glory will show her a

way to guide these good people in their final confrontation with the

Walkin' Dude, the hardcase, the Man in Black, please allow him to introduce

himself, Randall Flagg? While King gives her a real backstory,

strength, and fortitude, the fact that she is the only black character

is conspicuous. I feel this is narrow-mindedness on King's part, a lack

of imagination in a work that is intended to be the opposite!

Finnish translation, 1994

King has never shied from letting

it all hang out (something he may have gotten from goodbuddy Harlan

Ellison). This

book was written by a guy of his era, a Cold War kid. It's a

book of

its era too; that is, the late 1960s and 1970s. Its creation was

inspired by the kidnapping of Patty Hearst. The death of flower power

and the downfall of Nixon propel its engine (indeed,

The Stand is

so of its time that it presages both Three Mile Island and the Jim

Jones mass suicide in Guyana). The lyrics of Bob Dylan, John Lennon, and

Jim Morrison float through the prose and dialogue and epigrams. Springsteen too, but he's a '70s guy, so it fits that zeitgeist I'm talking about. Larry Underwood's rock star burnout reads more like late '70s scenario too... Warren Zevon, anyone?

Our villain Randall Flagg's nickname is

the Walkin' Dude, and he walks like a hitchhiker, but hitchhiking was

vastly out of public consciousness by the time the '90s arrived.

Hitchhikers weren't killers on the road, despite what the Doors said;

hitchhikers got

picked up by serial killers. So changing the

dates to 1990 and switching in Bush for Carter and so on

is just that: it changes only the dates and the names, not the psyche

of the characters, and country, involved. Like Glen Bateman's estimation

of Randall Flagg himself, this aspect of the book was a big nothing. And Flagg

is a big nothing, but not in a horrific way: nah, he's just a grinnin' fool, like Bill Paxton in

Weird Science or something.

German translation, 1985

People like to read about

themselves, about regular people in extraordinary situations, and King has always provided that pleasure. Larry Underwood's grueling passage through the Lincoln Tunnel is

certainly an all-timer sequence in King's output, and there are many

scenes of dire heroics, such as the shootout between our heroes and the men

who've been keeping several women as sex slaves is quite good:

Four men, eight women, Fran's brain said, and then repeated it, louder, in tones of alarm: Four men! Eight women! Nadine Cross's college experience with a Ouija board, in which Flagg contacts her years prior to the book's events, was a nice touch too in the expanded version. But these sequences are very few and far between, which I was not expecting at all. For such a long book it is curiously empty of import.

In fact I found

the latter half to be tighter in every aspect, and that climax,

long-maligned, not nearly as disappointing as I'd recalled. Reading about Flagg and his coterie of boot-lickers and hangers-on in Las Vegas who've formed a cult around him that would make Charlie Manson jealous is infinitely more interesting than those goody-two-shoes Free Boulder folks. Many readers have complained of the

deus ex machina, virtually

a literal "hand of God" (even noted as such by Ralph in the final

seconds) that brings about the climax. It has nothing to do with the travails

of Mother Abagail,

nor any of the people of Boulder, so there is no ultimate

confrontation between good and evil as the medieval-style cover art

suggests.

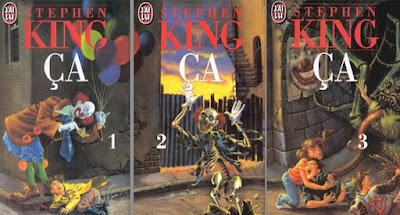

French J'ai Lu editions, 1992

It was

almost a relief, not having a giant ending that exhausts readers. This is, I know, the opposite of many readers' experience, who prefer the first half of the book. The 1990 edition expands, after their witnessing the nuclear doom of Flagg's Vegas, Stu and Tom's hard road back to Boulder, a bitter denouement that drags, I suppose, appropriately. So having Flagg reappear in the final pages struck me as pointless, a cheap twist...

Large-scale, good-versus-evil horror is not for me. My long-ago read of The Stand was the first inkling that I was outgrowing this pedestrian worldview. My other two big go-tos back then were Clive Barker and H.P. Lovecraft, who didn't deal in this kind of

Manichean duality; I preferred ambiguity and agnosticism, subversion and

confrontation, certainly not King's idea that "horror is as

conservative as a Republican banker in a striped suit." Today I've outgrown completely this "tale of dark Christianity" as King himself puts it in his intro.

While I wasn't actively reading the book, I was also watching HBO's devastating

historical drama

Chernobyl, an all-too-relevant coincidence. The show's

images of abandoned houses and tower blocks and burnt vehicles and starving pets and the

dead and dying bodies were utterly haunting, heartbreaking, gut-wrenching. Never

once did King's descriptions of similar ground-zero landscapes affect me the same

way; he's unable to scale the heights of his imagination with his pen. These grievous oversights and failures actually angered me: ask my wife about the rant I went on about how displeased I was with the book during our drive to a relative's house on Christmas Eve! Or rather don't ask my wife about my Christmas Eve rant. I mean and I wasn't even high.

It comes down to this, and I'll admit it seems almost churlish for me to say so, but I can not recommend either version of

The Stand. The 1990 uncut edition expands on the weaknesses of the 1978 version, making that book's faults even

more obvious, while adding new ones. Despite random strong passages and scenes, there is so much shallowness, naivete, and lack of commitment to the central idea—a grand battle between good and evil that never comes to pass—

The Stand left me disappointed in a very deep and lasting way. This surprised me a lot; I was unprepared for how very little I enjoyed this book.

While my rereads of two other King novels I was never fond of,

Carrie and

The Shining, were surprising successes,

The Stand remained as I'd found it nearly 35 years ago: foundering under its own weight and undone by a banal, half-baked theology. On this reread I noticed how larded it is with middlebrow observations of human relationships, American culture, and societal ties; and not nearly as profound as it thinks it is: all in all, a deeply superficial account of the end of the world. As a fan of vintage King I don't understand the novel’s esteemed status, other than nostalgia by fans who first encountered it as inexperienced readers. It pains me to say all that, but here I am, making my honest stand.