Everybody remembers their first

Joe R. Lansdale story.

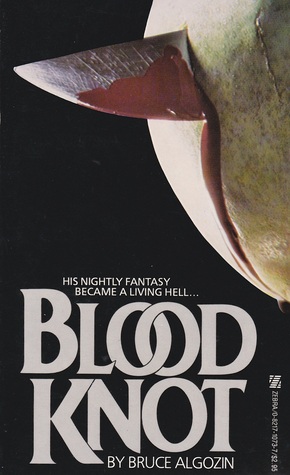

Mine was "Night They Missed the Horror Show," which I read in the 1990 anthology

Splatterpunks in January 1991 (its first appearance was in 1988's

Silver Scream but I must've missed it somehow). To say I was unprepared for this black-hearted tale of Texas high-school hellraisers who inadvertently stumble upon real-life horrors is an understatement. Like a sucker punch to a soft belly or a club to the base of the skull, "Horror Show" leaves you stunned, out of breath, a hurt growing inside you that you know won't be leaving any time soon. Hasn't left me this quarter-century later. I know Lansdale (b. 1951, Gladewater TX) would have it no other way.

Funny thing was, I craved that feeling. Sought it out. So within a couple months I'd tracked down Lansdale's 1987 novel

The Nightrunners (Dark Harvest hardcover 1987, paperback by Tor, March 1989). I recall coming home one afternoon from the bookstore I worked at with my brand-new copy, going into my room, locking the door and then reading it in one white-hot unputdownable session. That had never happened to me before; I usually savored my horror fiction over several late nights. But

The Nightrunners wouldn't let go. Lansdale's skill in doling out suspense and the threat/promise of the horrible things to come was unbeatable, evident from the first. He even tells you flat-out, after quoting a newspaper article about victims of a "Rapist Ripper," that

"no one knew there was a connection between the two savaged bodies and what was going to happen to Montgomery and Becky Jones." You know you got to keep reading after that!

The Joneses are a young married couple, living in Galveston, Texas, whose lives are shattered when Becky, a teacher, is raped by young men who were once her students in high school. She is haunted by the event, months later, can't even bear her husband's Montgomery touch. The nightmares are horrific re-enactments, almost as if her rapists are living in her head. Monty is a pacifist professor and he can't deal with how ineffectual the crime makes him feel; it throws his entire life philosophy into doubt. A conscientious objector to the Vietnam war, he worries that it's cowardice, not conviction, that may be his main motivation. Becky is horrified rather than being relieved when Clyde Edson, the teenage scumbag sociopath who led the attack and the only one caught by police, hangs himself in his jail cell: she'd seen his death in a vision. Monty, with his "sociological thinking," and a therapist try to explain it away, a result of her trauma, but Becky knows something worse is waiting. Monty's plan? Take her away to their friends' isolated cabin in the woods. Surely, they'll be safe there!

Kindle edition, 2011

Honorable, stand-up guy Clyde never named his accomplices, and so they're still out there, tooling around the night streets in a black '66 Chevy, eating up the lonesome Texas highways (

"Its lights were gold scalpels ripping apart the delicate womb of night, pushing forward through the viscera and allowing it to heal tightly behind it"), looking for trouble, always first to draw when it shows up. Like a mini-Manson, Clyde drew the disaffected to him, into his poisonous orbit; a crew of violent losers with nothing to lose. His best bud Brian Blackwood, however, is different: together the two of them fancy themselves Nietzschean "supermen" (or, as Blackwood writes in a journal,

"It's sort of like this guy I read about once, this philospher whose name I can't remember, but who said something about becoming a Superman. Not the guy with the cape"), ready, willing, and able to topple civilized society and live by muscle and wit, appetite and anger. AKA rape and murder, of course. And revenge.

1987 Dark Harvest hardcover

Here's where things get strange: one night Brian dreams, dreams of a god shambling up a black alley

"and somehow Brian knew the shape was a demon-god and the demon-god was called the God of the Razor." Lansdale shifts from his tale of gritty crime and violence into something surreal and grotesque. It is, in its way, absurdly beautiful.

...tall, with shattered starlight eyes and teeth like thirty-two polished, silver stickpins. He had on a top hat that winked of chrome razor blades molded into a bright hatband. His coat (and Brian was not sure how he knew this, but he did) was the skinned flesh of an ancient Aztec warrior... out of nowhere he popped out a chair made of human leg bones with a seat of woven ribs, hunks of flesh, hanks of hair, and he seated himself, crossed his legs and produced from thin air a dummy and put it on his knee... the face the wood-carved, ridiculously red-cheeked face of Clyde Edson.

(You can see that the cover artists--Joanie Schwarz and Gary Smith--actually read the book! God how I love that Tor cover) Brian learns that Clyde is possessed by this God of the Razor, and now Clyde is going to inhabit Brian and together they're going to find Becky and, in Clyde's charming parlance, "cut the bitch's heart out." With the God of the Razor there to guide their hand. And if Brian fucks up, there's a razor to be ridden on the Dark Side... forever. Idiot minions in tow as well as a bored teenage couple looking for kicks, Brian/Clyde begin their night run, rumbling through the countryside in that black Chevy, laying waste to any and all who get in their way. No one will be spared.

Woeful cover art for Carrol & Graf 1995 reprint

I haven't mentioned the many characters that inhabit the novel, men and women living the hardscrabble Texas country life Lansdale knows so well, using humor and sex to ease pain and poverty. Some of the folks seem like stereotypes but Lansdale always invests a knowing detail into them. He doesn't belabor characterization, but he knows it hurts the reader more when he hurts characters we care about. The teenagers are irredeemable evil, yes, smart yet deluded or stupid and easily led. Monty continually questions his manhood; Becky struggles to contain her fears and begin a normal life again. Despite the depths of sexual violence that Lansdale plumbs here--and make no mistake, he plumbs deep, disturbingly, humiliatingly deep, and there are moments where you'll want to put the book down and try to shake out an image from your head that he's put there--there is always an element of humanity; he balances his cold steel razor fear with an understanding of people in extreme situations. We can survive, if we fight. And if we can get our hands on a frog gig, all the better.

2013 trade reprint, dig the '70s color scheme

Don't get me wrong:

The Nightrunners is not a noble book; it is mean, it is nasty, it is ugly as hell in places and it doesn't flinch, ever. It's also vulgar and crude and clumsy--the less said about a flashback to Monty and Becky's "meet cute" scene the better--obviously the work of a writer not yet in command of his craft. But beneath its exploitative surface beats an energetic heart. In cinematic terms, the novel is kind of a hodge-podge of '70s and '80s horror, thriller, and crime entertainment. Peckinpah's

Straw Dogs is the obvious inspiration, I think, but one can also sense young Wes Craven and Sam Raimi nodding approval, while the Coen Brothers hang around in the background. Richard Stark and Elmore Leonard peek in every once in a while too. Going back to the '60s you can sense an AIP "wild youth" vibe when Lansdale describes that rumbling black Chevy and the teenage troublemakers inside.

1992 French edition: Children of the Razor!

Lansdale likes his humor icy black, Texas-corny, and in the direst of situations. While not as effortless as it would be in later novels, his bleak sarcasm and smart-ass attitude is threaded throughout

Nightrunners. Doesn't always work; this attitude can seem callous, particularly in the humor the teens find in hurting people. Some readers might find this a turn-off. Still, it's what distinguishes him from a couple other extreme writers of horror from the same era,

Jack Ketchum and

Richard Laymon. He's not as dour as the former or as dreary as the latter. He's unclassifiable. Joe R. Lansdale is his ownself, as he's always said, and I believe him. You will too.

In the years since this early novel, Lansdale has become more and more prolific (and even better at this writing thing), moving out of the cult ghetto, winning major awards (2000's

The Bottoms took the Best Novel Edgar Award) and having film adaptations made (2002's

Bubba Ho-Tep and 2014's indie crime flick

Cold in July, based on his 1989 book). His

personal Facebook page is filled with his terrific and honest advice about writing and the writing life. I've read quite a few of his '80s and early '90s novels and stories (try

The Drive-In from '88, the short story collection

By Bizarre Hands from '89, or

Mucho Mojo from '94) and enjoyed them, but it is

The Nightrunners that has stayed with me best: it is pulp '80s horror fiction at its rawest, nastiest, most unforgiving, most relentless. Behold the God of the Razor... but don't say I didn't warn you.

This post originally appeared on Tor.com in slightly altered form.