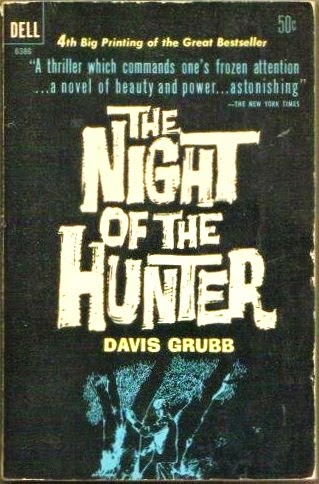

Known for penning the novel

The Night of the Hunter upon which the

classic 1955 movie was based,

Davis Grubb (1919-1980) was a West Virginia native well-versed in the pride, poverty, tribulations and superstitions that were endemic to that region. This collection of short stories ranging over 20 years,

Twelve Tales of Suspense and the Supernatural (paperback edition from Fawcett Crest, June 1965) includes some

Weird Tales works as well as tales first published in popular magazines like

Ellery Queen,

Nero Wolfe,

Woman's Home Companion, and

Collier's: you know, all the middlebrow publications of the mid-century that your great-grandparents might have read of a TV-less evening (

Cavalier too, but that was probably Grandad's privy reading).

Grubb's style has a slightly melancholy, forlorn (the variant "lorn,"

which I have never come across before, appears in places) note to it and

his scenarios are decent time-passers, characters familiar: drawling

ne'er-do-wells, laconic sheriffs, expansive judges, tempting women,

shrewish wives, innocent children, cool killers. The aptly-titled

"Moonshine" got me thinking of those Gold Medal

paperbacks from the 1950s of Southern sleaze and backwoods ribaldry.

That sensibility is everywhere, but not overwhelming; I wouldn't really

call it Southern Gothic, but there is just a hint of it at the edges.

From hardcover edition, 1964

While reading these stories I couldn't help but think of Grubb's

contemporaries in short genre fiction. While his stories aren't quite as

sensitively-wrought as

Charles Beaumont's or as matter-of-fact believable as

Richard Matheson's, as cold and cruel as

Shirley Jackson's,

Twelve Tales still has appeal. Readers fond of

Fredric Brown and

Gerald Kersh,

two other unclassifiable writers whose fiction has strong echoes of

crime, science fiction, suspense, and horror, should take note as well.

Most

stories end with a ingenious image of violence, perhaps that's even the

tale's

raison d'étre, but we all know this is the pulp template.

Nothing cuts too deep or too sharp, but you can see the bone in "One

Foot in the Grave" and "The Horsehair Trunk," two good and grim

revengers that echo

Robert Bloch's punning but without that author's black humor. "Busby's Rat" and "Radio" could have served as minor entries in

Ray Bradbury's

October Country, and "The Rabbit Prince" is at once sad and sweet as a spinster schoolteacher is given a glimpse of wild abandon that could have come from his pen when he was feeling kinder. "Nobody's Watching!" is set in the high-tech world of TV production, and it's the kind of thing I could imagine

Harlan Ellison writing about his early days, the dangers of the mediated image on the human mind... and body.

Hangin' with Bob Mitchum in the '50s. Lucky!

Orphaned children populate several of the short stories; of course endangered siblings form the crux of

Night of the Hunter (which, goddammit, I must read!). Grubb has a particular sympathy for them--as who wouldn't?--but he doesn't present them mawkishly as a lesser writer would. "The Blue Glass Bottle" highlights how children misunderstand the grownup world about them.

"Murder. It was a word. You heard the men say it at Passy Reeder's Store. Murder. It was black marks on the colored poster at the picture show house where the man clutched the red-haired girl by the throat." Grubb's writing shines here, with a slight

To Kill a Mockingbird vibe, and the final lines quite affecting.

One of the oddest stories is "Wynken, Blynken, and Nod," which evokes the famous child's rhyme to a macabre end. You may find the reveal a tad ridiculous but it's handled nicely:

"There is a moment--perhaps two--in the lifetime of each of us when the eye sees, the mind recoils, and all conscious thinking rejects what the eyes have seen." You might even think of

Daphne du Maurier.

Grubb can imbue a phrase like

"not so much as a single scratch" with the most unsettling of implications. That's from "Return of Verge Likens," one of my faves, two brothers who react quite differently to the murder of their father. It was self-defense! claims the killer, and the cops agree. Too bad the man who did the deed was Ridley McGrath,

"the biggest man in the whole state of West Virginia! Why, don't Senator Marcheson hisself sit and drink seven-dollar whiskey with Mister McGrath in the Stonewall Jackson lobby very time he comes to town? Don't every policeman in town tip his cap when Mister McGrath walks by?"

"That don't matter a bit," said Verge.

Arrow UK paperback, 1966

The collection concludes with the "Where the Woodbine Twineth," which was adapted for

an episode of "Alfred Hitchcock Presents" and included in

Peter Straub's excellent anthology for the Library of America,

American Fantastic Tales (2010). A little girl whose parents have been killed now lives with her father's sister Nell, who will not tolerate any dreamy foolishness from her new charge (all probably the fault of her brother's "foolish wife"!). Young Eva natters on about the "very small people who live behind the davenport," you know, Mr. Peppercorn and Mingo and Popo! Aunt Nell will have none of this, but when Captain Grandpa or whatever his name is arrives on a steamer from New Orleans with a Creole doll for Eva, things get interesting. Despite the use of an unwelcome (but context-accurate) racial slur, "Woodbine Twineth" ends on a clear, classic, sparkling note of pure unadulterated horror.

Twelve Tales offers old-fashioned pleasures for genre readers; not a classic by any means, but I think a handful of stories--generally, the last half of the book--are worth checking out. There's nothing as terrifying as Robert Mitchum lurking inside with love and hate tattooed on the knuckles of his hands, but then again... I'm kinda relieved there's not.