Wednesday, January 28, 2015

Friday, January 23, 2015

Evans Light and His Paperback Finds

Horror writer Evans Light has been having some great luck with his book-buying sprees recently, finding lots of books I was unfamiliar with. He has graciously allowed me to share their cover art. The title above, The Craving (Dell 1982), was one a TMHF reader was looking for, who provided a description of the cover which I posted on the Facebook page. Evans came to the rescue, ID-ing the book right away, one he'd just purchased himself! Screaming Whitman's Sampler, totally brilliant. Be sure to check out his (and his brother's) site, www.lightbrothershorror.com.

The Sharing (Avon 1984) shows some folks all going for--what? Moist brownies? An evil lust for moist brownies? Is that it?

The Heirloom (Pocket 1981) is by one of Graham Masterton's pseudonyms. '80s kids had all the fun...

Don't Tell Mommy (Pocket 1985) with more face-melting mayhem.

Masques (Berkley 1981) has a creeptastic voodoo doll and a nice tagline and that font I love, ITC Benguiat. Pronzini is a crime writer but his books were often marketed to horror readers; you can see this title's other covers here.

The Breeze Horror (Onyx 1988) Hungry hungry curtains! I find breezy winds rather foreboding, but will that work for a whole novel?

And a couple creepy kids to wrap up: Children of the Dark (Ballantine 1980) and Satan's Spawn (Avon 1988).

The Sharing (Avon 1984) shows some folks all going for--what? Moist brownies? An evil lust for moist brownies? Is that it?

The Heirloom (Pocket 1981) is by one of Graham Masterton's pseudonyms. '80s kids had all the fun...

Don't Tell Mommy (Pocket 1985) with more face-melting mayhem.

Masques (Berkley 1981) has a creeptastic voodoo doll and a nice tagline and that font I love, ITC Benguiat. Pronzini is a crime writer but his books were often marketed to horror readers; you can see this title's other covers here.

The Breeze Horror (Onyx 1988) Hungry hungry curtains! I find breezy winds rather foreboding, but will that work for a whole novel?

And a couple creepy kids to wrap up: Children of the Dark (Ballantine 1980) and Satan's Spawn (Avon 1988).

Monday, January 19, 2015

A Plethora of Poe

American author Edgar Allan Poe was born on this date, January 19th, in 1809. You may have heard of him, he wrote a coupla things worth reading...

Yr Humble Narrator at the author's grave site, 2012

Thursday, January 15, 2015

Throwback Thursday: H.P. Lovecraft and the Parody of Religion

(For Throwback Thursday, here's a short post I'd forgotten about from my old blog Panic on the Fourth of July, posted in 2009. Enjoy!)

(For Throwback Thursday, here's a short post I'd forgotten about from my old blog Panic on the Fourth of July, posted in 2009. Enjoy!) H.P. Lovecraft was a lifelong resident and antiquarian from Providence, Rhode Island, who supported himself by writing the most vivid star-flung nightmare fantasies of the early 20th century. His shadow over the field of horror entertainment since his death in 1937 is unparalleled and unmistakable. To say something is "Lovecraftian" is to intimate its awesome alien strangeness, as in, "Some early scenes in Ridley Scott's Alien (1979) are truly Lovecraftian."

In

Lovecraft's tales, gone were the dank castles of Count Dracula, the

Gothic laboratory of Dr. Frankenstein, the cross and the silver bullet

to destroy the beast, the pure of heart and the Lord's Prayer. He wrote

for the new scientific age of Darwin, Einstein,

and Freud, when our fears were no longer blasphemous monsters of

superstitious Old World folklore, but of the vastness of the universe

and humanity’s lowly place within it; terrors not of the soul, but of the mind.

"The

most merciful thing in the world, I think, is the inability of the

human mind to correlate all its contents. We live on a placid island of

ignorance in the midst of black seas of infinity, and it was not meant

that we should voyage far. The sciences, each straining in its own

direction, have hitherto harmed us little; but some day the piecing

together of dissociated knowledge will open up such terrifying vistas of

reality, and of our frightful position therein, that we shall either go

mad from the revelation or flee from the light into the peace and

safety of a new dark age."

"The Call of Cthulhu," 1927

Lovecraft's

infamous Great Old Ones are not, as some have insisted, simply evil

alien creatures, as Arkham House founder August Derleth posited and

promulgated in his own stories;

no, they represent the inability of humans to comprehend anything

outside their own earth-bound experience. From deep space and other

dimensions, these beings are not the saucer-eyed, woman-hungry Martians

of science fiction; these entities are vast, incorporeal, protean,

inconceivable. Degenerate cults worship them as gods, and Lovecraft at

once parodies and mocks notions of religion, spirituality, sacred texts, and transcendent knowledge.

An

atheist who, as he said, "hated and despised religion," Lovecraft saw no

real qualitative difference between, say, "Shub Nigurath, the Goat with

a Thousand Young" or "Past, present, future, all are one in

Yog-Sothoth," and "Transubstantion of the Eucharist" or "There is no God

but God." The dread Necronomicon is their bible; the acolyte's cry of "Iä! Iä!" is Cthulhu-speak for "Hallelujah!"

"They

worshiped, so they said, the Great Old Ones who lived ages before there

were any men, and who came to the young world out of the sky. Those Old

Ones were gone now, inside the earth and under the sea; but their dead

bodies had told their secrets in dreams to the first men, who formed a

cult which had never died. This was that cult, and the prisoners said it

had always existed and always would exist, hidden in distant wastes and

dark places all over the world until the time when the great priest

Cthulhu, from his dark house in the mighty city of R'lyeh under the

waters, should rise and bring the earth again beneath his sway. Some day

he would call, when the stars were ready, and the secret cult would

always be waiting to liberate him."

"They

worshiped, so they said, the Great Old Ones who lived ages before there

were any men, and who came to the young world out of the sky. Those Old

Ones were gone now, inside the earth and under the sea; but their dead

bodies had told their secrets in dreams to the first men, who formed a

cult which had never died. This was that cult, and the prisoners said it

had always existed and always would exist, hidden in distant wastes and

dark places all over the world until the time when the great priest

Cthulhu, from his dark house in the mighty city of R'lyeh under the

waters, should rise and bring the earth again beneath his sway. Some day

he would call, when the stars were ready, and the secret cult would

always be waiting to liberate him."

"The Call of Cthulhu," 1927

The final lines of "The Shadow over Innsmouth" (used so well in Stuart Gordon's 2001 film Dagon)

can be seen as a nightmarish twist on the Lord's Prayer: "And in that

lair of the Deep Ones we shall dwell amidst wonder and glory forever."

Compare: "For thine is the kingdom, and the power, and the glory,

forever and ever. Amen."

"Man

must be prepared to accept notions of the cosmos, and of his own place

in the seething vortex of time, whose merest mention is paralysing. He

must, too, be placed on guard against a specific, lurking peril which,

though it will never engulf the whole race, may impose monstrous and

unguessable horrors upon certain venturesome members of it."

"Man

must be prepared to accept notions of the cosmos, and of his own place

in the seething vortex of time, whose merest mention is paralysing. He

must, too, be placed on guard against a specific, lurking peril which,

though it will never engulf the whole race, may impose monstrous and

unguessable horrors upon certain venturesome members of it." "The Shadow out of Time," 1935

Wednesday, January 7, 2015

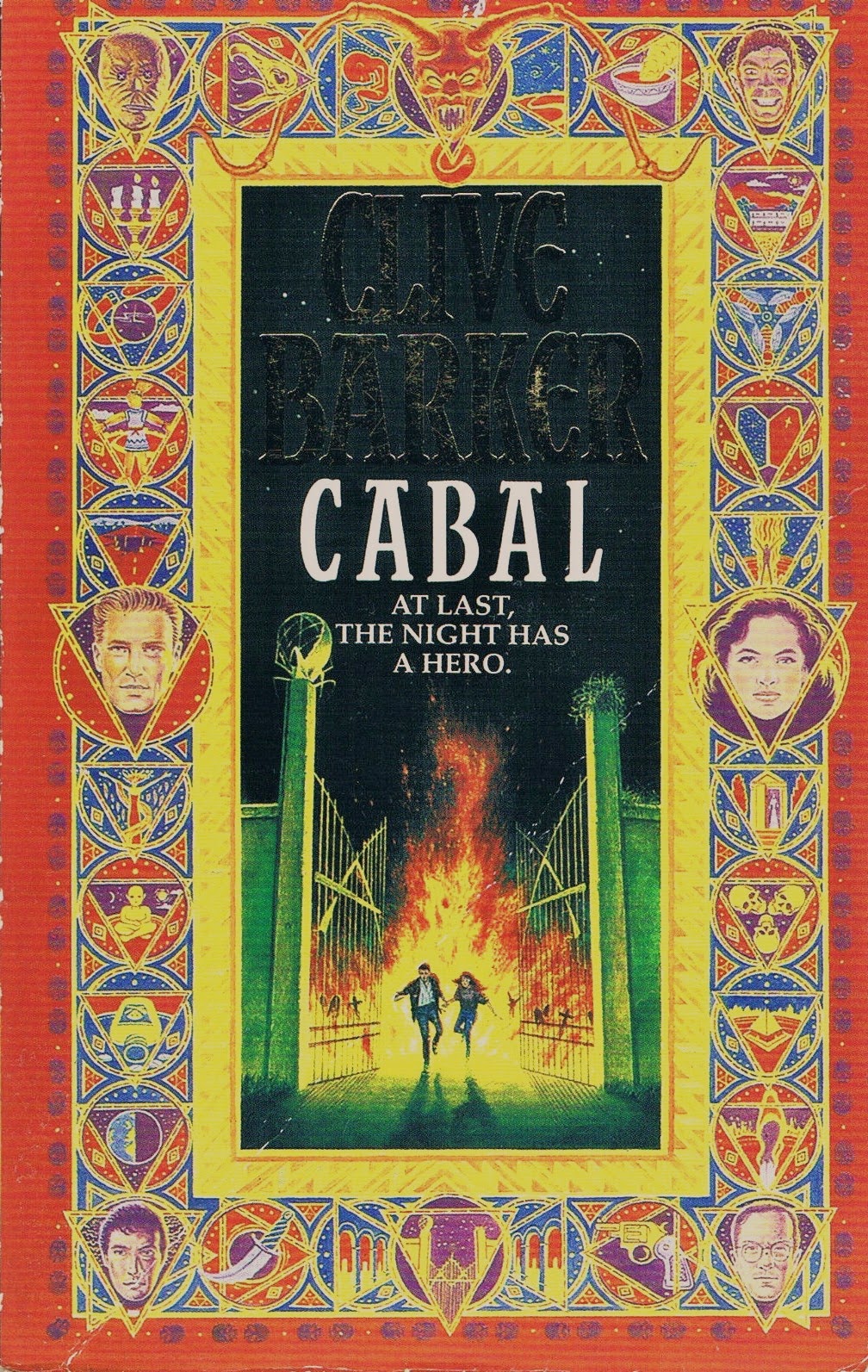

Cabal by Clive Barker (1988): Stand Me Up at the Gates of Hell

Weren't there, among those creatures, faculties she envied? The power to fly, to be transformed, to know the condition of beasts, to defy death?... the monsters were forever. Part of her forbidden self. Her dark, transforming midnight self. She longed to be numbered among them.

Another prime example of Clive Barker's consistent concern with monsters and the humans that dwell in their midst, Cabal came out at perhaps the height of his success as a bestselling horror author. The 250-page novella was published in hardcover in the US along with the stories from Books of Blood Vol. VI, while in the UK it was issued as a standalone title. Then a year later Barker began adapting this work for the screen as Nightbreed, the storied, troubled production of which probably most horror fans of that era are familiar with. I'd read Cabal twice but oh so long ago: once before the film was out in early 1990 and once not long after. A couple weeks ago I watched the recently released director's cut of Nightbreed and afterward reread Cabal. Not as a "compare and contrast" exercise, which is a bit too English Comp 101 for me, but the movie had gotten me thinking: how has a quarter century's passing affected my affinity for the Tribes of the Moon (a phrase found only in the film)? Would I still be as excited and eager about the Nightbreed as I am in this photo?

Clive Barker and me; he's signing my Nightbreed poster.

January 1991

He'd heard the name of that place spoken maybe half a dozen times by people he'd met on the way through, in and out of mental wards and hospices, usually those whose strength was all burned up. When they called on Midian it was a place of refuge, a place to be carried away to And more: a place where whatever sins they'd committed--real or imagined--would be forgiven them. Boone didn't know the origins of this mythology nor had he ever been interested enough to find out. He had not been in need of forgiveness, or so he thought. Now he knew better...

Harper Collins, Toronto, 1989

Boone's entrance to Midian is foolhardy and near-fatal: a bite from a Breed member "more reptile than mammal" called Peloquin--who can instantly sense Boone's guiltless, Natural self--gives Boone a kind of immortality, which comes in handy when Decker brings the police force to Midian and they shoot Boone dead. But he's not dead. Now, as a walking dead man, he's become the Breed, and escapes the morgue. But his return bodes unwell for the inhabitants of Midian, who fear he will reveal them to Man. Boone defies the laws of the Breed when he rescues faithful Lori from blood-hungry Decker outside Midian's gates, which causes all sorts of problems. However, here in horror Boone's truest self's revealed:

In Decker's presence he'd been proud to call himself monster: to parade his Nightbreed self. But now, looking at the woman he had loved and had been loved by in return for his frailty and his humanity, he was ashamed.

His will making flesh smoke, which his lungs drew back into his body. It was a process as strange in its ease as in its nature. How quickly he'd become accustomed to what once he'd once have called miraculous.

To make up for his folly Boone demands to see Baphomet, the Nightbreed god who created Midian as a haven for these creatures. Following Boone, Lori gets a glimpse of a column of flame and:

There was a body in the fire, hacked limb from limb... this was Baphomet, this diced and divided thing. Seeing its face, she screamed. No story or movie screen, no desolation, no bliss, had prepared her for the maker of Midian. Sacred it must be, as anything so extreme must be sacred. A thing beyond things. Beyond love or hatred or their sum, beyond the beautiful or the monstrous or their sum. Beyond, finally, her mind's power to comprehend or catalog.

This meeting is a moment out of all man's primitive religions: the holy fire, the sacred other, that once seen cannot be unseen, and once experienced the profane is transformed. There is no going back. Boone is a Moses and Baphomet his Yahweh; prophecy foretold. Barker has always gotten good mileage out of this comparative mythology aspect of his fiction, mileage I'm always happy to travel. While Lovecraft parodied and satirized religious beliefs with his "Yog-Sothothery," Barker recognizes that humans have a need for transcendence, but not one that annihilates, one that transforms. Boone bravely embraces his true nature; he is no Outsider reaching out in cowering fear and touching a mirror.

And so the tale continues, and closes, with redneck cops--led by the truly odious Eigerman--and a gaggle of shotgun-wielding yahoos on loan from Night of the Living Dead descending on Midian thanks, again, to Decker. He's set on killing Lori, who now knows his secret. He loathes the Breed, cannot wait to participate in their destruction: "They were freaks, albeit stranger than the usual stuff. Things in defiance of nature, to be poked from under their stones and soaked in gasoline. He'd happily strike the match himself." They rout the Breed in a final confrontation that will create a new enemy and destroy another. Boone is renamed Cabal--"an alliance of many"--by Baphomet and ordered to rebuild ("You've undone the world. Now you must remake it"). Lori and Boone are reunited at last.

But the Nightbreed are not ended. Irony abounds, even until the very last line: "It was a life." Lori's words to Boone after he rescues her from death and gives her his Breed balm (heh, and yes, he does this figuratively and literally) are, "I'll never leave you," which the astute reader will recognize as the words in the opening paragraph, words Boone considers a lie. What does this irony mean? Barker knows how to leave readers wanting more by undermining expectations; the tale ends just as it's beginning!

Fontana UK movie tie-in, 1990

In a 1989 Fangoria interview with journalist/author Philip Nutman, Barker talked about the motivation in making Cabal a novella:

"I wanted to do the reverse of what I did in Weaveworld, which was to really cross the t's and dot the i's, give every detail of psychology and so on. In Cabal I wanted to present a piece of quicksilver adventuring in which you were just seeing flashes of things, Boone, Lori, the Breed, each character's psychology reduced to impressions. Part of the fun for me was to write it in short, sharp bites."I quote this because it explains what at first I disliked about Cabal on this reread: strokes were too broad; too much time giving impressions and not specifics; characters were moved about like a kid playing with action figures--so much to-ing and fro-ing! After the short sharp shocks of the Books of Blood and the epically-drawn dark fantasy of Weaveworld, maybe the novella format was not good idea. But as I read, Barker's writing grew in its conviction; he's more adept at the contradictions and ambiguities of murderers and marauders than he is with the banalities of everyday life. Still, some frustrations:

Decker's psychopathy could have been expanded; the creepiest moments belong to him, like when Ol' Button Face, the glib nickname Decker has for his killing mask/personality, chatters hungrily to him while it resides in his briefcase. The conflict of his inhumanity versus that of the Nightbreed is sketched in here and there, none more illuminating than when Barker writes of Decker: "The thought of his precious Other being confused with the degenerates of Midian nauseated him." Decker is a fascinating character; the witless police not so much.

Fans of the film looking for bizarre monstrosities will have to be satisfied with only glimpses of the Nightbreed. Unlike some of the detailed creatures that inhabited Barker's earlier short stories like "Rawhead Rex," "In the Skins of the Fathers," or "Son of Celluloid," the reader is given mostly impressions. With a surrealist's eye Barker gives us intriguing hints but doesn't belabor the descriptions. When Lori first descends into Midian:

...was

it simply disgust that made her stomach flip, seeing the stigmatic in

full flood, with sharp-toothed adherents sucking noisily at her wounds?

Or excitement, confronting the legend of the vampire int he flesh? And

what was she to make of the man whose body broke into birds when he saw

her watching? Or the dog-headed painter who turned from his fresco and

beckoned her to join his apprentice mixing paint? Or the machine beasts

running up the walls on caliper legs? After a dozen corridors she no

longer knew horror from fascination. Perhaps she'd never known.

1989 Pocket Books edition

Yes, Barker's mantra has always been thus. In the monstrous there is beauty; the normal course of daily things is a horror. But I wanted more. Cabal works better if one considers it as allegory, as fable, and its politics are a liberal dream: evil is not evil, it's an alternative lifestyle! Witness the callous crude cruelties of doctor, cop, and priest: the first is a psychopath literally wearing a mask; the second an egomaniac concerned only with his brand of law, order, and notoriety; the last is a hypocrite. The undoing will be at the hands of these traditional authorities; it is they who will squeeze the life out of the untamed, the unwanted, even the undead. Cabal ends clearly stating that the enemies are still active, still enraged, still stung by humiliation and eager to bring a comeuppance.

Poseidon Press 1988 US hardcover

I guess I'm saying there's a theoretical distance in Cabal which prevents me from really, truly enjoying it the way I do so much of Barker's other work. Maybe it's the movie, which I like all right in its new incarnation but have never been overly fond of (although this version is a more faithful adaptation, Nightbreed remains irredeemably cheesy in a way Cabal is not), intruding upon my imagination; I can't at all recall how I envisioned the story before its film adaptation. And it reads, and ends, like a prequel. This has been a problem with Clive Barker since, well, since 1988. He's always intended to continue the story of Cabal. To continue the story began in The Great and Secret Show. And Galilee. And Abarat. Later this year we'll finally get The Scarlet Gospels, which apparently concludes the stories Harry D'Amour and Pinhead, an apotheosis of two aspects of Barker's art. His ambition might outreach his vision, his health, and dare I say it, his life. But again, it pays to see Cabal as a fable, a beginning, a story for us about us: fans of the Breed are the Breed, "The un-people, the anti-tribe, humanity's sack unpicked and sewn together again with the moon inside." That is a story that continues, and continues, and continues.

Barker '88

Sunday, January 4, 2015

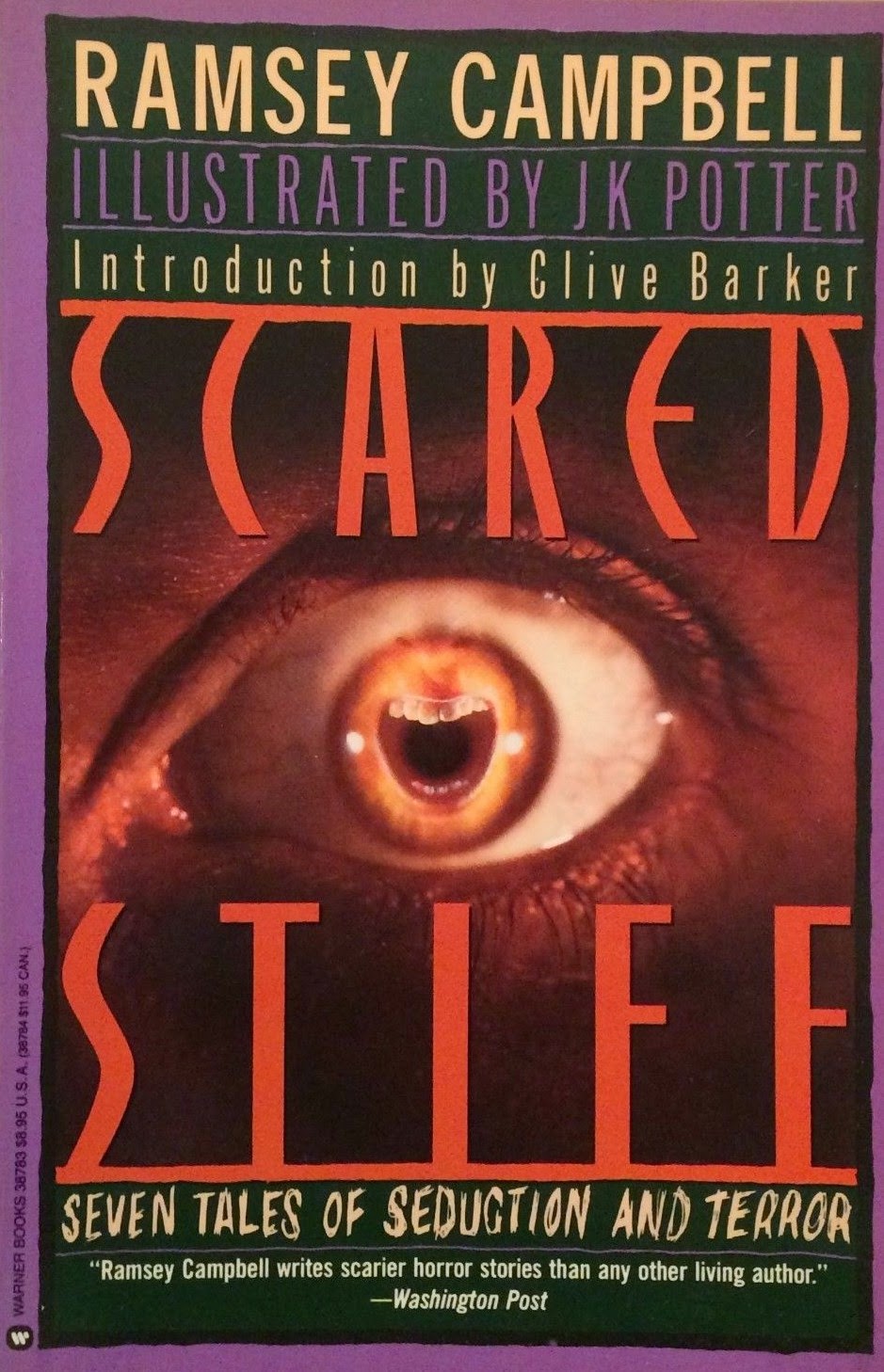

Ramsey Campbell Born Today, 1946

Birthday greetings to the esteemed Ramsey Campbell! He was one of the--if not the--first modern horror writers I began reading in the 1980s that wasn't named King or Barker. First purchased was Cold Print, a collection of his Lovecraftian tales. Next up for me was 1987's Scared Stiff, his later collection of stories of "sex and death" or "seduction and terror," with intro by, of course, fellow Liverpudlian Clive Barker. I haven't revisited Scared Stiff (heh) since those days, but hope to reread it this year.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)