Oh that smirk on the face of blow-dried '80s-'do dude, it's the worst. He's even lifting an eyebrow like burying you alive is just some kind of joke. Folks in the know might be reminded of a classic

Vault of Horror cover, or even a vintage punk

record. Alas, in

David Lippincott's wholly unremarkable

Unholy Mourning (Dell Books, Nov 1982), only a few moments achieve this kind of horror goodness. A dorky mortician with the disturbing name of Jorbie Tenniel is besieged by a homicidal "Voice" which tells him to bury various townspeople alive to avenge the death of his twin brother. Or something. It's been over a week since I finished reading this and it took me around three weeks to trudge through all 366 pages, so forgive me if I'm a little iffy on the nitty-gritty.

Lippincott (1924 - 1984)

To begin with, I couldn't even with the name "Jorbie." Oh god it's just the worst, a mish-mash of consonants in the diminutive (I know I'm risking a

Joey Jo-Jo moment here). His brother, dead by Jorbie's own sociopathic indifference as the tale begins, has the far more normal name of Kenneth. Like many horror novel siblings,

They neither needed nor wanted other children; they lived in a private world of their own. No surprise that Jorbie

particularly resented intruders into this world. They didn't always listen to him or do what he commanded the way Kenneth did. A-ha! The prologue was promising, I'll give it that, when Kenneth drowns in Lake Michigan due to Jorbie's daring him to swim too far. Later Jorbie finds Kenneth's water-logged rotting corpse when it washes into some rocks he visits on the shore. It's a life-changing moment:

There was no wonderful, happy life after you died at all. You just rotted and fell apart... He would never trust anyone again.

You can see

Unholy Mourning gets off to a halfway decent start. Now it's present day, we're introduced to 20-something Angie Psalter, who's cut from the Talia Shire-as-Adrian cloth. A young lay teacher at a parochial school, she lives with her drunkard dad who, we learn a few chapters later, attempted to rape one of Angie's little schoolfriends years before during Angie's birthday party (everyone knows and is cool with that, though, Lippincott points out. And not ironically. Too bad for that little friend, oh well, these things happen). Angie spies Jorbie at a dinner/dance she's working at the school, and thinks he's kinda swell, despite being an outsider as he's a mortician (does that really make one an outsider? Lippincott implies yes). Jorbie had had a promisingly brilliant but short-lived stint in medical school, which he left and went back to the family mortuary business after his father's death. Of course these two lonely misfits start courting, I guess is the term.

Corgi Books UK, 1981

This courtship is nonsensical and abusive. Not even borderline abusive. Of course I'm looking at this 1982 novel through today's lenses, but that only means that victim/abuser relationships have never changed. Her relationship with Jorbie is practically a checklist of abuse: when he goes into one of his brooding moods, gets caught in a pathetic lie, or even brandishes a chair at Angie, she always tries to figure out what she said or did to set him off. He even gives her a black eye! It happens over and over, a tiresome refrain. Twice more a bewildered and hurt Angie tried to apologize for doing something she wasn't even sure she had done.

Repeatedly Lippincott makes awkward authorial observations out of nowhere that Angie would have been better off if she'd just gotten away from Jorbie as fast as possible, but Angie is so put-upon she believes it's all her fault and promises to do better "next time." At one part early in their affair, Jorbie shows Angie his crematorium and other work areas, and he's left out

dead bodies of people she knows for her to see, "Oops, I forgot you knew her!" and makes horrible dumb jokes—posing a dead Jewish man so he's making a Nazi salute—while she mildly rebukes him. Mildly. Angie, DTMFA!

Corgi Books UK, 1983

Lippincott makes no attempt to evoke sympathy for any character. Angie is a dishrag/doormat, while Jorbie is the worst kind of arrogant person even discounting his penchant for burying people alive. He verbally abuses his assistant, Pasteur (a pathetic lumbering giant on loan from horror cheapie central casting). The police chief, Hardy Remarque, is okay I guess, but standard cop stuff in stories like this, two steps behind what's really going on (personally I'm rarely into cops in my horror fiction). Some religious characters, nuns and priests, yawn, to help people through their grief after Jorbie's through with his victims. Jorbie's crippled father Caleb is interesting, sad, hiding family secrets, that kind of guy. The only truly likable character, Edith Pardee, a sweet thoughtful older woman, is around only to tell the dysfunctional lovebirds how they truly belong together and the whole town—it's always "the whole town" in these books—thinks the two belong together. It's utterly depressing.

Turns out, Jorbie is going after people who were at the lake the day his brother drowned, they or their now-grown children, injecting them with curare, which he'd stolen from his old school lab, with a tiny hypodermic needle he has specially made hidden in a ring on his finger. It knocks out people's nervous systems, so they can't move or feel, like living death—

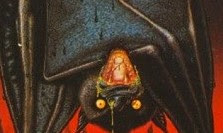

suspended animation. Yep. The person gets ill, then "dies," basically, and Jorbie pretends to embalm them but he doesn't: he puts them in a coffin and they're buried that way. Then they wake up, six feet under. Shivery indeed... but Lippincott's handling of this gruesome endeavor pretty much saps the scenario of real horror. In the hands of a committed writer, the experience of waking up in a buried coffin is about as ripe as it gets for full-blown fear and madness. The stepback cover artist for the UK edition, Terry Oakes, got it right:

This dud is an excellent example of how the popularity of horror was considered a cash-in for publishers and writers who knew nothing about the genre and cared even less. Lippincott's style is square, dull, obvious, and belabored. Can't imagine what his other mainstream thrillers are like. Horror content was needed and writers were needed to provide it no matter what. I imagined him hunched over his typewriter with a publishing agent behind him, Lippincott looking back over his shoulder and saying "Is this what you want? Horror? Am I doing it right? Horror is scary and violent, right? Huh, right? Booooo!"

I grinded through pages of blocky conversations, banal insights, psycho first-person ramblings, turgid plot mechanisms, and general unpleasantness that offered not a whisper of the weird or eerie. There's an autopsy scene on one of those poor folks, that kinda works, I'll give the author that, but his central idea of revenge and the manner in which Jorbie goes about it—which anyone should be able to guess, as there is nothing supernatural going on in the novel—is unbelievable, even for a horror novel.

Dell Books, 1984

The climax is rendered with professional precision, sure, and its horribleness is notable, but it is all cliche and tired trope and predictable jump scare, with a denouement you know is coming. "This is horror, right? Is this how you do it? It is, right? Boo, argh, aaah!" I wish there'd be a scene of the exhumation of Jorbie's helpless victims: god, I can scarcely imagine! Nope, this is not how it's done. At all. Dedicated reader of horror do yourself a favor: buy a copy of the book for its cover, maybe, but be sure to avoid actually reading it.

Am I finished with this review? Is this it? Okay, good, I can't wait to get back to the actual

good horror novel I'm reading now...

.jpg)