If you've followed Too Much Horror Fiction at any time over the past 13 (!!!) years, you'll know Clive Barker is one of my lodestars of genre fiction, up there in my own personal pantheon with H.P. Lovecraft, Stephen King, and Harlan Ellison. It's not just Barker’s fictional writings that have influenced and inspired me, but also the many interviews and intros to other books he did in which he discusses his beliefs about what horror (and other speculative fictions) is about, can do, and what it reveals about our humanity, our culture, our desire for something more than our daily lives. Given that I started reading him as a high school student in 1987, Barker's world has had an untold impact on me, both within the genre and out.

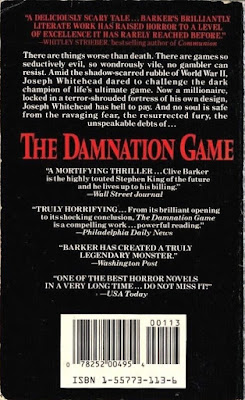

First published in hardcover in the UK in 1985 and then in 1987 in the US, The Damnation Game (Charter Books paperback, July 1988, Marshall Arisman cover art), was anticipated on both sides of the Atlantic as a major novel debut. Barker was the enfant terrible of then-contemporary horror fiction, after his 1984 collection of genre-expanding stories, Books of Blood, were propelled by that famous Stephen King quote. Barker was ready to take over the mainstream. Its impetus was maybe more commercial than artistic; short story collections have always been seen as "lesser" product by publishers. As the editor of Sphere Books told Barker after unexpected success with Books, "Now do something sensible and write a novel... something we can really sell!"

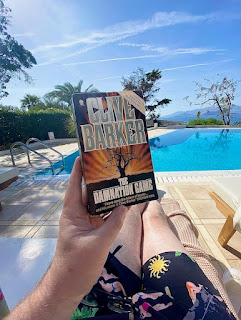

A somber, gloomy, somewhat subdued tale of men and their debts, desires, and debaucheries, The Damnation Game helped affirm Barker's place at the top of the Eighties horror pantheon. For many years this was Barker's sole "horror" novel, in that it had none of the unique fantastical world-building that he would become known for in such subsequent epics as Weaveworld (1987), The Great and Secret Show (1989), and Imajica (1991). After rereading Books for this blog, I then reread The Hellbound Heart and Cabal, so I figured I'd continue chronologically with this guy. I read Game several times over 30 years ago, recall liking that Barker had made the leap from short story to novel, that the detailed eye he had for transgressive terrors was not lost in this longer format.

The opening chapter, set in bombed-out Warsaw, crackles with dread and enormity, yet with a strange sense of freedom to be gained from playing games, chancing fate, plying one's wits against a devilish opponent—ideas Barker returns to again and again. In his mind this faceless gambler began to take on something of the force of legend. Then the narrative shifts to the 1980s, where we meet protagonist Marty Strauss, a thirty-something prisoner doing time for a botched robbery, debts owed from gambling, life lost, security van empty. Offered parole if he accepts the could-be-more-dangerous-than-prison job of bodyguard for world famous industrialist Joseph Whitehead, Marty accepts, wary though he is.

He doesn't know Whitehead

is hiding out in his vast, well-secured London estate, with laconic bodyguard Mr. Toy and a menagerie of dogs, from the mysterious Mamoulian, aka The Last European—the fellow from the

opening. What follows is Marty learning the truth of Whitehead's wealth,

why his teen daughter Carys is a junky, and other unsavory facts about a world of woe just a whisper's breath away.

Whitehead's revelation

to Marty about his and Mamoulian's history in those WWII ruins contain a

mystery as something few Americans truly grasp. Various set pieces

underscore Barker's notions of the existential dread of nothingness

("nothing is essential") so at odds with the more common horror

dichotomy of good and evil, Heaven and Hell, God and the Devil. The two

young American missionaries who appear at the end, empty-headed Chad and

Thomas, offer a somewhat witty addition to the grim proceedings; they

can only interpret what they're seeing through the inanities of

Christianity, their Pastor Bliss, their hunger for the Deluge to wash

all sinners away. In Chad's mind waters—red, raging waters—mounted into foam-crested waves and bore down on this pagan city.

Much, perhaps most, of Barker's appeal was and is his ability to pluck beauty from the

monstrous; his prose style, sleek and polished, unhurried and measured, is informed by classic

continental literature and film, with imagery inspired by European cinematic

masters such as Cocteau, Antonioni, Bunuel, Fellini, Fassbinder. There is a pathetic dinner sequence with Whitehead's aged cronies and available young women drinking copious amounts of wine in a brightly-lit room, decorated only by a grotesque painting of the Crucifixion, that seems right out of a socialist satire about the insipid appetites of the rich. The old man had wanted to see him naked and rutting.

The scenes with Breer the

Razor-Eater, Mamoulian's dogsbody, and his unholy passions pedophilia, cannibalism,

necrophilia, whose rotting body as a reanimated corpse parallels in

physical form the moral corruption in the characters around him, are pure classic Clive:

...something

in his chest seemed to fail, a piece of internal machinery slipping

into a lake around his bowels. He coughed and exhaled a breath that made

sewerage smell like primroses... He was moving into a purer world—one

of symbols, of ritual—a world where Razor-Eaters truly belonged.

I let my own mother take this to the beach to read

and she left it on her blanket and the tide came in.

NEVER LEND BOOKS.

All Barker's strengths are on display, scattered throughout the book. Irony, opposites,

contrasts: delicate petals falling onto human wreckage, cities laid to

waste beneath spring skies, "death at laughing play in a garden of bone and shrapnel." Barker has always delighted in such contradictions, believing they get at a truth unreachable by simple black-and-white binaries. This approach lends an air of maturity to the proceedings, a sophistication rarely seen in the horror offerings on the same shelf. I recall reading the US hardcover when it came out, and indeed that format made this gruesome tale somehow respectable.

The notion of "nothingness" as a final terror is one Barker would address in various works throughout his career. Here, we have the room in Mamoulian and Breer's hideout—who has kidnapped children in the cellar shiver—which Marty discovers.

This wasn't the adventure he'd thought it would be; it was nothing. Nothing is essential... all of it was like a fabrication. A dream of palpability, not a true place. There was no true place but here. All he'd lived and experienced, all he'd taken joy in, taken pain in, it was insubstantial. Passion was dust. Optimism, self-deception.... Color, form, pattern. All diversions—games the mind had invented to disguise this unbearable zero. And why not? Looking too long into the abyss would madden a man.

As I said above, I don't think Americans have a concept like existential

nothingness the way people who were close to the atrocities of WWII

were. Maybe I'm generalizing, but that's my serious impression; not for nothing is Mamoulian nicknamed "the Last European." He remembers the horrors. As a

young guy myself with some intellectual pretensions of my own beginning to

sprout, Barker appealed to me precisely because he used horror as a way

to get at deeper truths about human nature, not simply as a vehicle

for cheap thrills and messy bloodshed.

Oddly, unlike the Books of Blood excesses of surreality and guttural fears, Barker only refers to atrocities—he literally keeps using that word, "atrocities"—rather than regaling us with more poetic descriptors as only he can. Early on, some gruesome dog deaths play a large part in a scene of confrontation (and resurrections; the creatures would've looked spectacular in a practical-effects kind of way in a movie), particularly now knowing what a dog-lover he is—a cheap shot at unsettling readers? As I said: Damnation Game was his bid for success, and so

perhaps he felt he had to tone down his tendency to terrorize readers

with things never before imagined.

Worms, fleas, maggots—a whole new entomology congregated at the place of execution. Except that these weren't insects, or the larvae of insects: Marty could see that plainly now. They were pieces of flesh. He was still alive. In pieces, in a thousand senseless pieces, but alive.

On this reread I found the novel somewhat—dare I say?—tame, believe it or not. In his bid for bestsellerdom, Barker eschews the epic flights of fancy and imagination that so marked his previous output for a more mainstream narrative, the Faustian deal gone bad (of course there are no Faustian deals that go well).

Stretched out over 430 pages, the bizarre imagery he conjures up loses

its impact and the story falters. Yes, there are very good set-pieces of perverse gore and grue, and the secret history of Whitehead and Mamoulian's long relationship is darkly fascinating, but pages of irrelevant detail, unfocused narrative, and a somber tone slow the proceedings into a dreary crawl. Rather than emboldening him to stretch out for the long haul, it

seemed this novel format constrained Barker's visions. These are all first-novel problems, indeed.