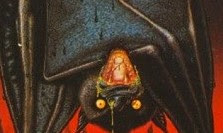

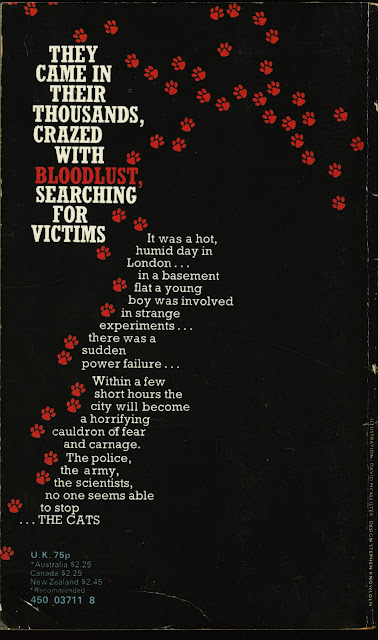

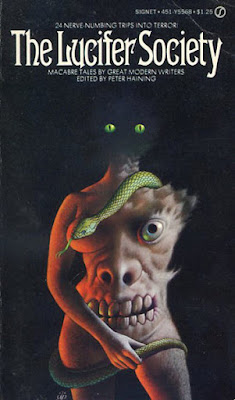

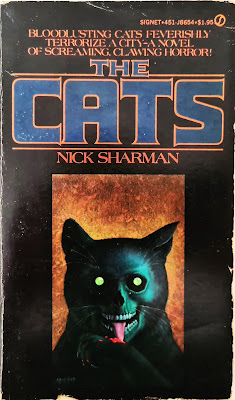

And who can forget that great line from the Scorsese version of Cape Fear, with deranged De Niro snarling, "Granddaddy used to handle snakes in church, granny drank strychnine"? I haven't seen that flick since the grunge era and yet have never forgotten it. I was reminded of it recently when I picked up a book that's long taken up residence on my bookshelves, The Accursed, a slim novel published by Signet in November 1977. With a perfectly-rendered cover of innocence and evil, reduced to their most primeval, Paul Boorstin's first novel is one of the many titles Signet put out that feature animals run amok. This time, the animals are snakes of various deadly varieties, all part of the worshipful country cult ceremonies held by one Preacher Varek. [He] seized a hissing Indian cobra, the scaly coils writhing in his grasp, its forked tongue, sophisticated sensor both taste and smell, flicking, bringing minute chemical particles back to be analyzed in the Jacobsen's organ above its jaws.

At the edge of Desperation Swamp in Clay-Ashland County, South Carolina, sits Thornwald Memorial Hospital, a time-worn edifice showing its age in the sweltering clime of mid-July. Run by a power-hungry administrator with no medical degree and rotating crew of indifferent, autocratic, and/or horny employees, the hospital is hardly a place one would want to spend any time in, much less perform as a doctor or recuperate as a patient. Unfortunately for Dr. Adam Corbett, a man of character and do-goodery vibes, perform here he must, and when he learns that the newborn baby of poor swamp denizen Mary Ann Cotter is suddenly and inexplicably dead, a baby he elivered, he is not convinced of the coroner's explanation of crib death: Adam would have to tread lightly or lose his job.

Early on, we learn that this crumbling hospital was built on the site of a Confederate infirmary that, in 1863, was attacked and laid waste by Yankee soldiers, forever a place where bloodshed and black powder had poisoned that strip of land overlooking the swamp forever... the only thing the property was good for was a hospital or a graveyard, take your pick. More than once I was reminded of the late great Michael McDowell and his Avon paperbacks, and the Southern territory, both physical and psychological, that he would mine in a few short years. Author Boorstin certainly doesn't have the meanness, the mercilessness, the weird vivid characters, the deadly droll narrative of McDowell's works, but that's fine; Boorstin acquits himself well in these proceedings.

We're not here for finely-wrought characterization of human foible, we're here for monster mayhem, and Boorstin has the skills for just that, getting right at the skin-crawling repulsion that coiling serpents engender in us: Man's world seemed a simple matter of neat geometry, straights lines precisely drawn to meet at sensible right angles. But this cold-blooded hunter curved, twisted, a devious, sinewy, supple being eluding rational explanations.

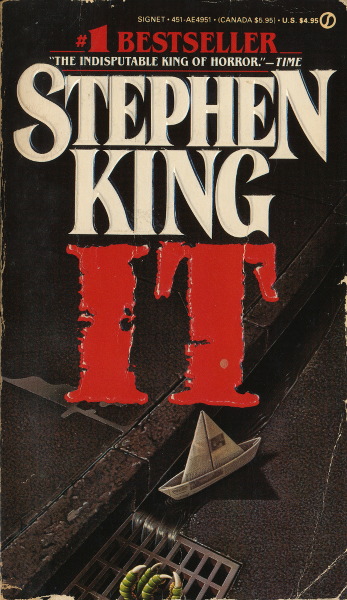

The paperback's bio page states that he was inspired to write The Accursed while "filming in the Amazon interior" and spending time in the hot South Carolina sun. Boorstin's experience is wide-ranging, a professional documentary filmmaker/producer and TV screenwriter; his father was American historian and author Daniel J. Boorstin. His next novel, Savage (which I own but have not read), also happens to feature some fantastic cover art:

The Accursed especially snaps to life when Preacher Varek, a giant of a man shrouded in black, [his] head shaved bald by a straight razor, is onstage. Suspense ratchets up when he comes into contact with Jean, Dr. Corbett's pregnant wife, rescuing her when her car gets stuck in the mire, and shames her for wanting to have, you know, her baby in a hospital with modern medicine and all. The preacher contradicted everything the young doctor stood for and Adam worried where Jean's naive belief in this swamp healer might lead.

Other unsavory characters abound, mostly snake fodder, and Boorstin isn't above the cheap thrills of the Seventies, like the sexy nurse who caresses

herself—not too tacky now!—and meets an inspired "sex and death" end in a bubbly bathtub. Unhooking her bra with one hand, she rubbed the icy champagne bottle along her bare, sweaty breasts, beds of moisture condensing around the enlarged crests of her nipples. Or the poor burn victim bastard who tries to get an old nurse to read him dirty magazines, utterly immobilized, a free meal for a ferocious reptile. Maynard's eyes peered over the coils of his murderer, the orbs nearly popping out of their sockets from the pressure...

Yeah, I gotta say, Boorstin has written some truly tasty scenes of serpentian gore and horror. There are two climactic scenes of confrontation; the first is good, yes, but the second is a fuckin' ripper, and I could easily see the fake blood flying and the mechanical snake writhing and roiling in a cheap TV-hospital set. Her blood mingled with the serpent's, to drench her nightdress in gory impasto.

Like the previous novel I read, The Night Creature, this book got better as it went on, doling out its suspense level in a workmanlike manner, crisscrossing plotlines, very much in a cinematic narrative. You're definitely getting you your dollar-ninety-five's worth of B-movie entertainment. Did Boorstin miss a few opportunities to imbue a little more, I dunno, gravitas here and there? Sure, I guess; there are several times when the author's voice rings out over the standard cliche melodramatic proceedings that you wish he'd have given this baby one more writerly polish. But even its more lackluster moments didn't last too long. Boorstin's adeptness at describing ophidian destruction makes The Accursed a satisfying pulpy read, and its inclusion on the very cover of Paperbacks from Hell is thus the perfect place for it.

The intruder seemed to congeal out of the moist and heavy air, gliding stealthily,

almost as if knowing this was a place of such fragility that it must trespass with infinite care.

Thick as a fire hose, it slithered slowly from the air-conditioning vent: five, ten, fifteen feet long, and still extending, an uninvited guest so out of place in the room it hardly seemed possible the interloper was there at all...

.jpg)