One of horror's great scenes is when Jonathan Harker is confronted by three vampire women—the "weird sisters"—in

Dracula. As one of them kneels at Harker's side, he hears

the churning sound of her tongue as it licked her teeth and lips, then he

closes his eyes in langourous ecstacy, waiting for the moment when her

sharp white teeth will pierce the flesh on his neck... Wonderful stuff (till of course the Count rushes in and ruins this tender moment). And I thought of this bit of sexual dread when I first encountered

Catherine L. Moore's famous 1933 pulp horror/science fiction story, "Shambleau."

This was Moore's first story, believe it or not, and its popularity hasn't dimmed since it first appeared in the November 1933 edition of

Weird Tales, having been included in dozens of science fiction and horror anthologies across the globe. There is something so primal about this work that nine decades have not dulled its power, and I think it operates as a kind of ur-text for erotic horror.

Featuring a semi-heroic character that Moore would use again and again named Northwest Smith, "Shambleau" at first comes across as standard pulp for its day: Smith is a space pilot, an outlaw, a smuggler, going about business in a kind of Wild West city called Lakkdarol, an outpost on Mars: a raw, red little town where anything might happen, and often did (Smith is obviously a precursor to Han Solo; this type of pulp adventure is just what George Lucas would repurpose for the Star Wars universe).

A wild mob is chasing down

a berry-brown girl in a single tattered garment whose scarlet burnt the eyes with its brilliance. Smith draws his laser gun in defense of the poor creature as she evokes a kind of sympathy in him, even though he's no hero. He talks down the mob, who keep shouting "Shambleau!" The leader informs Smith

"We never let those things live," but Smith informs

him that Shambleau is his, he's keeping her. This puzzles and astonishes the crowd; as they disperse, the leader spits out at Smith:

"Keep her then, but don't let her out in this town again!"Obviously relieved, this girl known only as Shambleau cannot speak much English, and Smith is perplexed by the bloodthirsty disgust the mob had evinced towards her. Their brief conversation is halting, but she manages to get out, "Some day I—speak to you—in my own language" (nice foreshadowing!). Smith knows he needs to get her someplace safe, like back to his sparse, rented room. As they walk, he notices others on the streets staring after him and the turban-headed alien girl in disbelief.

Back in his room, Smith tries to get the girl to eat, but she will not. He tells her she can stay safe here, and he goes out to do his business:

Smith's errand in Lakkdarol, like most of his errands, is better not spoken of. Man lives as he must, and Smith's living was a perilous affair outside the law and ruled by the ray-gun. He returns that evening, drunk on “segir,” or Martian booze, and is surprised to see Shambleau still there. Yes, he's drunk... and suddenly horny. They embrace...

Her velvety arms closed around his neck. And then he was looking down into her face, very near, and the green animal eyes met his with the pulsing pupils and the flicker of—something—deep behind their shallows—and through the rising clamor of his blood, even as he stooped his lips to hers, Smith felt something deep within him shudder away—inexplicable, instinctive, revolted. What it might be he had no words to tell, but the very touch of her was suddenly loathsome—

With a cry of "God!" he pushes her away, recalling that wild look in the eyes of that street mob. Shambleau falls to the floor and her turban slips. Smith had thought her bald, but no, quite the opposite is true:

a lock of scarlet hair fell below the binding leather, hair as scarlet as her garment, as unhumanly red as her eyes were unhumanly green. He stared, and shook his head dizzily and stared again, for it seemed to him that the thick lock of crimson had moved, squirmed of itself against her cheek.

Smith blames this "squirming" on too much too drink, tells the girl to sleep in the corner, and then gets into bed, where he dreams strange dreams beneath a dark Martian night, of some nameless, unthinkable thing ... was coiled about his throat . . . something like a soft snake, wet and warm, sent little thrills of delight through every nerve and fiber of him, a perilous delight. He is like marble, rigid, unable to move, fighting against it, till oblivion takes him and then, bright morning. Dismissing this “devil of a dream,” he tells Shambleau she can stay again, but he'll be leaving Lakkdoral in a day and after that, she'll be on her own.

C.L. Moore, c. 1940s

It was not until late evening, when he turned homeward again, that the thought of the brown girl in his room took definite shape in his mind, though it had been lurking there, formless and submerged, all day. "Formless and submerged," you say? Freud would, as it's said, have had a field day. Shambleau still has not eaten, still speaks in halting English obscurities like "I shall—eat. Before long—I shall—feed. Have no worry." Smith brilliantly asks her if she lives off blood, and she scoffs: "You think me—vampire, eh? No—I am Shambleau!" Well, that clears things up.

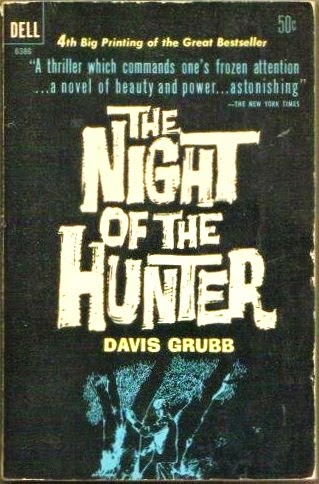

Where I first encountered Shambleau

That night brings a fuller realization of the horror that is Shambleau, and Moore spares nothing in her efforts to reveal what a danger to the rational human this alien is. Smith wakes to see Shambleau teasing him as she undoes her turban, allowing those scarlet locks to writhe and glisten in an obscene tangle, drawing Smith in helplessly. It's as if he recognizes what she is...

And Smith knew that he looked upon Medusa. The knowledge of that—the realization of vast backgrounds reaching into misted history—shook him out of his frozen horror for a moment, and in that moment he met her eyes again, smiling, green as glass in the moonlight, half hooded under drooping lids. Through the twisting scarlet she held out her arms. And there was something soul-shakingly desirable about her, so that all the blood surged to his head suddenly and he stumbled to his feet like a sleeper in a dream as she swayed toward him, infinitely graceful, infinitely sweet in her cloak of living horror.

Jayem Wilcox’s illustration for Weird Tales

Moore goes on in this amazing pulp fashion, overheated prose all silken seductive slidings, wet and glistening tentacle tresses like serpents, eager and hungry as they crawl towards this man frozen in fear... and desire. As she embraces him, she murmurs, "I shall—speak to you now—in my own tongue—oh, beloved!" Whew. Smith is bewitched, nearly hypnotized, a drug addict now, his identity subsumed into the hungering that Shambleau is, welcoming mindless, deadly bliss.

this mingling of rapture and revulsion all took place in the flashing of a moment while the scarlet worms coiled and crawled upon him, sending deep, obscene tremors of that infinite pleasure into, every atom that made up Smith. And he could not stir in that slimy ecstatic embrace—and a weakness was flooding that grew deeper after each succeeding wave of intense delight, and the traitor in his soul strengthened and drowned out the revulsion—and something within him ceased to struggle as he sank wholly into a blazing darkness that was oblivion to all else but that devouring rapture.

Like the femme fatale of a noir story, Shambleau promises heaven but delivers hell. Only the arrival of a space-pal named Yarol saves Smith; Yarol engages in a last-minute feat of derring-do, as he recognizes the alien for what it is, recalling in him ancient swamp-born memories from Venusian ancestors far away and long ago. Moore concludes her wild tale with the two space friends discussing the origins of Earth myths, an alien race, half-forgotten legends, a race older than man... you know the stuff! Yarol insists that if Smith ever sees a Shambleau again, "You'll draw your gun and burn it to hell."

The science-fiction setting of "Shambleau" is beside the point—this story is all about the shivery-delicious erotic abandonment delirium, and that exotic scarlet-maned alien woman who made many striking paperback covers possible. Delving into forbidden sensuality, notions of addiction, and debased pleasures that I'm sure few others were exploring in pulp magazines then, "Shambleau" is fully realized, imagined with audacity, holding nothing back, its voluptuous vibe making it a favorite of 1930s pulp fans and beyond. Not too bad for a brand-new author.

While horror as a genre is so often concerned with revulsion, fear, despair, and the like, Moore seemed to be clued-in to the uncomfortable fact that horror also can explore forbidden, attractive, addictive desires that polite society deem

unacceptable. But as psychologists understand, desire and disgust are rarely opposites; they mingle, coalesce, to beckon us towards

our doom... and we’d have it no other way.