Perpetually riding around the school grounds on his squeaky tricycle, Simon weirds out students and faculty alike. Susanne tells Chris he's got a hateful look on his punchable little face too. And also, what of the recent accidental deaths of several promising teenage boys there? And why does Mrs. Karen Catterby, Arthur's smokeshow of a wife and Simon's mom, have such a bad reputation on campus? And suddenly taken such a liking to Chris himself?

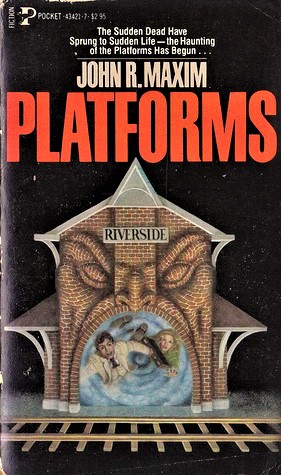

Featuring one of the grandest of all Paperbacks from Hell-era covers, by the fantastic Lisa Falkenstern, Tricycle (Pocket Books, August 1983) by Russell Rhodes, seems to promise Bad Seed levels of Creepy Kid Horror. That's a pretty tall order. Can it deliver?

The setting of a preparatory school was fine with me. Personally I'm fond of tales of professors and academics and college/university life in horror, so that was one point in the book's favor. Then there are a couple illicit sex scenes get things going nicely, that's good too. After the one that opens the novel, a fiery, helpless death: "I'm dying," he cried, "I'm dying!" Holding his face, the flaming boy whirled around in tight circles. His lungs gulped a last searing breath, then exploded within him as he toppled forward into the inferno. Okay, we're rolling right along!

But I noticed some issues soon after. Chris is kind of a wienie, and his attempts at teaching seem condescending; his feelings of inadequacy don't evoke much sympathy in the reader. Our author is more concerned with the banal gossip cocktail party

chatter of rich academic folk ("I don't care what you say, Linda, slacks and that blouse don't belong at the Academy. The thing's open practically to her navel"), which sure can be entertaining, but at the expense of other aspects—like horror itself. There's a lot of pages spent on literary classroom discussions—Shakespeare, Hemingway, other fine fellows, etc.—and a burgeoning friendship between Chris and Lucas, the student assigned to read aloud for him and assist in his coursework. Of course that leads to twinges of baseless gay panic!!1!

As (slasher-style and post-coital) deaths mount, Chris slowly starts to suspect the incredible: He, Christopher Hennick, at one time big man on campus, was at the mercy of a little five-year-old. Fear gripped him. It was all so very simple, so logical, so inevitable. I mean, all that goddamn squeaking of the tricycle wheels following him around, what other conclusion could he make?!

The tale reaches its climax in the school as the suddenly raging waters of the Connecticut River surge over the grounds, rising into the halls and stairwells and gym, where Christopher must battle his unseen enemy alone after everyone else evacuates. And oh shit, now a fire's started! In this last section, Rhodes delivers what I found it to be a convincing and well-staged finale, with some decent mounting suspense and a couple plot twists. Nothing revolutionary, you'll probably see 'em coming, even if some don't quite seem to square with what has been happening all along.

Rhodes, who was an adman by trade while he also produced fiction, writes with a serviceable, polished pen, and while nothing ever made me cringe, nothing sparkled for me either. He misses lots of opportunities he's set up for himself. Too often, Rhodes writes at a remove, like he's afraid to get granular as we say today. When Chris is trapped alone in a classroom with rattlesnakes, I was sure the rattlesnakes Chris hears would be revealed as an auditory prank on his blindness, but no: they're real. Yet Rhodes makes only a half-hearted attempt at conveying such distinctive creatures, which have to rank among the most frightening and fearsome on all the earth. "You know the rattlesnake, or Crotalina," the boy continued, "represents the highest type of serpent development and specialization."

Same with Milton, Chris's seeing-eye German Shepherd, another distinctive animal that Rhodes seems reluctant to include the interesting particulars of (I will warn you, the poor dog is killed eventually). Susanne disappears. Tricycle is definitely market fodder, commercial unit shifter, designed to give minimum thrill for maximum profit, an adman's idea of "horror." Rhodes's other titles seem like standard thrillers of the Seventies, spies, KGB, technology, super-hot ladies who have it all and want more, with back cover copy like "bizarre orgies, brain-searing terror, and the nightmare secret of Hitler's human experiments," awesome, I guess, but not my kinda thing at all.

It's easy to tell the author isn't a horror writer, probably wasn't even particularly interested in the genre; as I said, Tricycle was simply another title in the glut of paperbacks saturating book racks of the day. The novel's intensity level reaches about that of a TV-movie, desiring to be nothing more than a paycheck for Rhodes and a couple hours' diversion for the reader. I didn't expect much more, and honestly expected much less.

Tricycle is not a forgotten horror classic, and is better characterized as a suspense thriller especially since the ending wraps up the preceding events all too neatly. (When someone shouts "Satan's whore!" you'll wish that was a literal thing rather than just a misogynist slur.) Rhodes doesn't offer up much creepy atmosphere or dread, there is nothing supernatural going on, but the book did keep me turning pages over a few snowy days. Okay, okay, I skimmed here and there, don't think I missed much.

That yellow Hamlyn UK edition from 1985 is creepy, but just doesn't have that je ne sais quois of Simon bearing implacably down on you on the Pocket Books version, an image I found deeply unsettling when I saw it on the supermarket book racks as a kid. Alas, Simon isn't even close to being in the Creepy Kids Hall of Fame, but with an all-timer cover like this, Tricycle definitely belongs in your paperback horror library.