In his erudite introduction, Alan Ryan (1943-2011) provides a background and the impetus for this anthology, making note of how the short story has always held a sort of precarious position in American letters, and how horror is often at its very best in the format. Writers who speak on panels at fantasy conventions very often find that their audiences are most knowledgeable and most vociferous when the subject is short fiction.

Grant (1942-2006) was famed for his understated, elusive, and whispered brand of horror fiction; for some readers, entirely too understated and elusive. His stories here, seven in all, read pretty much the same as all the other Grant I've read: sometimes good, sometimes meh, and a couple times excellent. My tastes have moved past Bradbury-esque small towns at night, cold winds blowing autumn leaves across empty streets and onto regular folks' porches and windows, with kids climbing trees, dads in the garage and moms in the kitchen, grampas in the easy chair. Sure, behind those windows lurk realistic "horrors" like the indignities of aging, disintegrating marriages, childhood nightmares, coming back home to family strife... but his touch is often too gentle, eschewing as he does most violence and bloodshed.

That said, I will note the highlights of his contributions. He's adept at putting in that final turnabout line that might give the reader an intellectual chill, and, especially in the title tale, ably describes the true aches and pains of loved ones' mortality: it was the dying he saw [in her] every day for a year, the wasting, the shrinking, the growing into the grave from the inside out.

"That's What Deaths Are For" and "Family" well utilize his penchant for trapping his characters in a metaphysical hell, forced to relive/re-enact trauma for, well, eternity (at least, that's what I think is happening; Charlie Grant, master of elusion). "And We'll Be Jolly Friends" is a perfect example of Grant's melancholy M.O., and I'm not surprised it's the only story of his here that was reprinted, collected in his best-of Scream Quietly in 2016. Small town, parents, friendship, memory, wounding, death, and worse: present and accounted for, in Grant's slightly fractured, stream-of-consciousness prose:

go crazy

no, you ain't, you're just scared man, that's all

yeah, well, I don't wanna die

then stop bitching and hang on

jesus, i'm tryin', i'm tryin'

Tem in early 1980s, (photo by Karen Simmons, from Tem's FB page)

Next up are Tem's stories, also seven in number, and generally my favorites here. Tem's approach seems to me to be the most "modern," and one that other writers would employ as well. At times he can be, like Grant, a mite too obscure, but his mix of surreality and the quotidian hit me in the sweet spot. "The Men and Women of Rivendale" hides its menace till the end, hinting with imagery of mouths and red eyes again and again, subtle but insistent. "Spidertalk" won me over, with a frightened child, a caring teacher, and a menace both outside and inside the schoolhouse. The end of this one is shivery apocalypse, a common human fear becomes overwhelming both as symbol and substance; a perfect example of Eighties short horror fiction. But her fear was a living thing with a mind of its own, that would not respond to her own sense of reason.

Loved "Simon's Wife," top-tier stuff, a realistic tale of modern love and adultery. A woman travels to a married man's home while his wife is away, and faces her fears head-on when Simon is called away on business for a few hours the morning after their consummation. Unnerving, at times unpleasant, but for me, a real winner. I wandered this house like a ghost, no familiar possession of mine in sight, a lost traveler without a landmark... landmarks of Simon's wife, whose name I did not yet know, whose picture I was forming by irresistible slow degrees.

Her other stories, "The Tree: A Winter's Tale," "The Vampire Lover" and something something about a unicorn, I mostly skimmed: Lee's writing is sure and strong, all blood-drenched—yet not particularly scary at all—fairy-tale vibes, but my taste for that kind of medieval lore and imagery is practically nil. Still, I'm sure others whose tastes do run in that direction will find them perfectly satisfying.

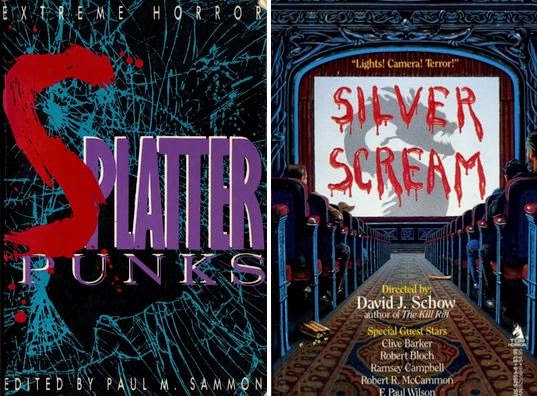

All in all, In the Blood is a perfect little starter for getting familiar with the more sophisticated styles of Eighties horror: literate yet chilling as it exposes the secret recesses we hide, highlighting those fears without resorting to excessive bloodshed or random limb-pulling (although there is a bit of that, here and there). You've got Grant's homespun domestic horrors of the everyday; Tem's sometimes surreal, sometimes esoteric, sometimes gritty entries; and Lee's lush, romantic, adult Gothic dark fantasies. Splatterpunk would come along in a year or two to rabble-rouse the grown-ups, sure, but much of what is written here is as about as good as horror fiction got back then. In the Blood will allow readers to look back and get a taste of these three authors' personal worlds of darkness, and what grave discoveries they have revealed.