Monday, November 3, 2025

Seance on a Wet Afternoon by Mark McShane (1961): And She Ain't What You'd Call a Lady

Friday, September 26, 2025

The Final Three Titles in the Paperbacks from Hell Reprint Series

These are highly sought-after titles, very rare on the secondhand market. Publication will be 2026. I hope you guys are excited to get your hands on these guys; I know we are all thrilled to unleash these horror fiction classicks once again upon an unsuspecting public...

Tuesday, September 2, 2025

RIP Chelsea Quinn Yarbro (1942 - 2025)

Monday, August 4, 2025

Orphans by Ed Naha (1989): We're a Happy Family

But Orphans is about none of these things. Published in November 1989 by Dell, this slim little novel by Ed Naha is competently, if unimaginatively, written, occupying that weird little subgenre space of kinda-sorta medical/science fiction horror (meh) with undead-gone-amuck (yay!). Naha is mostly in young adult fiction gear, writing at the most basic, one-dimensional level, refusing in any way to engage in insight or metaphor. Every character seems to be smiling all the time; indeed I have never read a book in which the word "smile" is invoked so often and so lazily, often several times on a single page.

Naha, a horror/mystery screenwriter/novelist, keeps the story moving, sure, his evil kids creeping out our main teacher character, but I never felt involved or intrigued. References to fog aren't enough to evoke true atmosphere, and characters who exchange banal jokes and tired flirtations just drift off the page. However, once we learn what is really going on with these creepy kids around town, things start to get juicy. Bloody. Gory. In fact, it gets almost to Re-Animator-levels of ridiculous B-movie violence. Unexpected, after such a PG-rated buildup.

Recommended lightly, and solely for the last third or so when shit gets gnarly. Otherwise, unless you're as obsessed with the cover as I am, you could probably skip it. And speaking of that cover, can anyone make out the artist's signature? "R.S. Br__"? Bottom right corner? I'd be ever so grateful if any of y'all could help ID this guy!

Sunday, July 13, 2025

Moths by Rosalind Ashe (1976): She Loves Naked Sin

This moody, erotically-charged cover art, by American romance illustrator H. Tom Hall, is perfectly fit for a sophisticated novel of doomed romance and obsession; I bought this paperback over a decade ago solely for its melodramatic atmosphere. I knew nothing of author Rosalind Ashe (1931-2006), and assumed the title, Moths, referred to the hapless male victims of a magnetic, alluring, possibly dangerous woman of incomparable beauty and passions. And... I was right.

The blurb comparison to Daphne du Maurier and her classic 1938 novel Rebecca is apt, though Moths doesn't reach the heights of suspense and emotional turmoil of that work. How could it? Yet this novel offers some good escapist fare, kind of what they're calling "romantasy" today, I think. The style, first person by an Oxford professor, is quite a bit plummy; I was constantly Googling his various allusions and references and poetic quotes to truly grasp and appreciate what was happening. Personally I find a lot of British culture, of whatever class, very interesting (piqued by decades-long obsession with the first wave of punk rock in the mid-Seventies), so this was fine and dandy for me. Other readers might take this as a warning, however, who don't have patience for an academic approach to such goings-on.

Penguin UK, 1977

There, also exploring the grounds, he meets the Boyces, a couple eager to make the place their own: James, another professor who is less committed to his work than to his mistresses; and his enchanting wife "Mo" (short for Mnemosyne, Greek for memory, and mother of the Muses, not too pretentious now!), who charms Prof. more than Dower House itself. Prof. Harry is able to befriend the two and thus finds himself invited into the home and their lives... and passions. James was her senior by ten years, a self-made academic... She was the last of a line of penniless aristocrats... In California, or on another social rung, she might have turned flower-child, perhaps Jesus-freak. As it was, she had an altogether unusual charm...

Ashe weaves a luscious stew of supernatural hints and erotic trysts in a delightfully dated Seventies style, very Jolly Old England, very gender-normative, very femme fatale. But is the femme fatale a ghost, a possession, an imagination? Who is this madwoman who, as the title explicitly implies, draws hapless men into her fiery embrace? Bodies turn up, cops are on the case, a diary is read revealing murder... poor Harry, can't he catch a break? This woman, Mo, (also called Nemo, which is Latin for "no one"—not too pretentious now!) is alluring, even unto death. Mood swings, migraines, to put up with her idiosyncrasies requires utmost submission, because you know the sex gonna be goood. Never had she been more lovely, more violently alive. The Regency actress who inhabited her seemed positively recharged by another victim: the dead thriving on the dead.

Friday, July 11, 2025

Interview with The Book Graveyard

Thursday, July 3, 2025

Live Chat with Me on Saturday, July 5th!

Monday, June 16, 2025

Too Much Horror Fiction Updates...

Hola amigos, long time since I rapped at ya! Got some horror (all good) news you can use...

I've written two introductions for two new horror anthologies: one was published at the end of 2024, The Rack: Stories Inspired by Vintage Horror Paperbacks, edited by Stoker Award-winning author Tom Deady, from Greymore Publishing; order here. Also, the brand-new Claw Machine, compiled by an old East Coast pal of mine who now also resides in Portland. You can order it from Little Key Press here. Both feature horror/science fiction/speculative lit stories that I think will appeal to TMHF and Paperbacks from Hell fans. It was definitely an honor to have been asked to write for these books!

Last but certainly not least: Grady Hendrix and I, along with Valancourt Books, have decided to wrap up the Paperbacks from Hell reprint series with three more titles, thus ending the line with an even two dozen works. But the titles have not been finalized yet! We're discussing a few books, but as you know, tracking down publication rights, and then convincing people to have their books republished, is tricky business; the stars have to align just so.

The moving parts are: books we all three like; the book is entirely out of print (no ebook/audiobook either); the original paperback is somewhat rare/expensive in the secondhand market; the author/estate is willing to have the book reprinted; and the promise of potential sales. As the years have gone on, checking off all those boxes is incredibly difficult. We've reached complete dead ends on several titles we've wanted. So we've all agreed, unfortunately, the end is here. I'll say we are looking at some "classicks" that a lot of people want to get their grubby mitts on, but that's all I will say for now.

Alas, we cannot reprint several notorious works that people have been asking about over the years: Eat Them Alive, The Voice of the Clown, and The Little People. For various and sundry reasons, the rights to these three remain completely unavailable to us. Frustrating and disappointing, I know, but I think the other titles were hoping to reprint will be quite well received! I will announce as soon as we've decided and gotten the rights signed off on.

Okay, back to reading, and hopefully getting some reviews back up on here...

Thursday, June 12, 2025

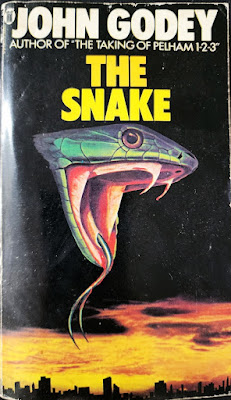

The Snake by John Godey (1978): My, My, My Serpentine

Enter The Snake: a 1978 thriller from a writer named John Godey. This was the crime fiction pseudonym of Brooklyn-born author Morton Freedgood, who had worked in NYC's film industry for all the giant movie companies, like Paramount and 20th Century Fox. As noted on the cover of the 1979 Berkley paperback, Godey previously wrote The Taking of Pelham 1-2-3, which was made into a 1974 movie that also captured NYC at its most lawless. Letting loose a giant slithering atavistic reptile into the gleaming greenery of Central Park must have seemed like a no-brainer to the author, especially in the wake of Jaws. The cover of the original hardcover captures it nicely:

Godey seems to know every inch of the city, doling out places names and addresses like any reader will know exactly what he's talking about (ah, New Yorkers!), and I often plugged in such into Google Maps to get a clear view of the specific environs the action was happening in. His depiction of the titular creature is both scientifically sound and aesthetically unsettling. The reasoning for its arrival and escape is believable in its randomness, a backstory both intriguing but also blackly comical in a way, and very NYC-coded. "Two dead in less than twenty-four hours, that's one thing... People die all the time. But the other thing, the politics, that's serious."

Characters are familiar: the beleaguered cop, the cocky young herpetologist, the lovely journalist, the sweaty mayor, the religious nuts who make it their mission to find and kill the demonic reptile, plus various hapless victims introduced and dispatched with maximum suspense. Godey may be writing a slick bestseller, and he's a bit above the pulp pay-grade; still, lots of vulgar '70s slang and profanities and ethnic slurs you'll remember from the movies of the day, with less enlightened folks going about their daily grind in a city that can swallow you whole—and now even has the ability to inject fast-acting fatal venom right into your veins. New York City really has it all, don't it? "Any other city, if somebody got bitten by a snake, the public would blame the snake. Here they blame the mayor."

Saturday, February 15, 2025

Under the Fang, edited by Robert McCammon (1991): The World is a Vampire

Nothing, it seems, or very little, to save ourselves. Thus is the setup for the stories in Under the Fang (Pocket Books, Aug 1991, cover by Mitzura), under the auspices of the Horror Writers of America coalition, with editing duties by iconic bestselling paperback author Robert R. McCammon. Akin to the zombie apocalypse anthos based on George Romero's movies, Book of the Dead (1989) and Still Dead (1992), (which of course hearken back to 1957's I Am Legend) all the stories exist in this new world, with each author bringing their own special methods of madness to the proceedings.

Virtually all the vampire anthologies published prior to the early

Nineties were collections of classic stories, moldy golden oldies by the

likes of Bram Stoker, Polidori, EF Benson, Crawford, Derleth, et al.

Esteemed editor Ellen Datlow gave us Blood is Not Enough in 1989 and A Whisper of Blood

in 1991, which featured all-new vampiric works by the cream of the

genre's crop. I'll confess: I've read neither, even though I've owned

them since Kurt Cobain was still alive. But those two volumes seem to be

the first that showed that the old symbols and themes of vampire

fictions could be given fresh new life at the end of the century.

They've won. They come in the night, to the towns and cities. Like a slow, insidious virus they spread from house to house, building to building, from graveyard to bedroom and cellar to boardroom. They won, while the world struggled with governments and terrorists and the siren song of business. They won, while we weren't looking...

He handily sketches out the scope of the situation in a couple pages, setting us up for the tales to come. Second is his story "The Miracle Mile," of a family's drive to an abandoned season vacation spot and amusement park. Vampires have of course overrun it, and Dad is pissed. With his signature mix of corny sap and derivative horror, McCammon delivers perfectly cromulent reading material. It's just that I always find him square and dull and earnest, and not my jam whatsoever.

The recently-late Al Sarrantonio's "Red Eve" is an effective slice of dark, poetic fantasy in full Bradbury mode, which was common for him. I have no idea who Clint Collins is, but his brief "Stoker's

Mistress" is a high-toned yet effective bit of metafiction about

vampires "allowing" Bram Stoker to write his "ludicrous" novel Dracula... Shades of soon-to-be-unleashed Anno Dracula. Nancy A. Collins had already had her way with the vampires;

"Dancing Nitely" is a perfect encapsulation of the modern image of the

unholy creature: they all want to live in an MTV video scripted by Bret

Easton Ellis. Contains scenes of NYC yuppies dancing under blood spray

at an ultra-hip underground vamp bar, called Club Vlad, with a neon

Lugosi lighting up its exterior. We may cringe looking back at it today,

but back then this style was au courant du jour.

Late crime novelist Ed Gorman delivers an emotional wallop in "Duty," powerfully effective even though I was half-expecting how the turnaround was going to happen. I gotta try one of his full horror novels! Richard Laymon

does his his usual schtick of adolescent ogling and rape fantasy

scenarios rife with toxic masculinity in "Special," this story ends on an unexpected

note of enlightenment. Better than other things I've read by him, but not enough to make me a fan.

Together, Chelsea Quinn Yarbro and Suzy McKee Charnas pit their own fictional vamps—Count St. Germain and Dr. Edward Weyland, respectively—against one another in "Advocates," the most philosophically ambitious work here; no surprise, as both women approached the vampire as a concept in their other writings. Could've been better I felt, less than the sum of its parts.

On to the finest stories within: my favorite was Brian Hodge's

"Midnight Sun," which is so well-conceived in scope and execution I

daresay he could've written an entire novel using his scenario. Muscular and convincing, its setting of a military outpost in frozen wastes makes it a standout; the conflict, not only between humans and vampires but also between vampires themselves give the story a real moral heft. A close second was "Calm Sea and Prosperous Voyage," by Chet Williamson, in which a loving husband and wife experience tragedy and woe after escaping into a cabin in the woods. Tough, moving, unsettling stuff.

Other stories here, by authors both known and unknown, run up and down the scale from ok sure fine to oh well whatever nevermind. This might not be the best antho of the era I've ever read, but the quality of prose is very high—this was the HWA, after all—even if the story itself doesn't quite succeed. Me, I could've done with some more graphic bloodshed/drinking, or classic Lugosi/Lee-style vamp action in the good old Les Daniels' tradition. No matter; your mileage may vary as well (PorPor Books enjoyed it maybe a smidgen more than I did). Overall, I'd say Under the Fang is an easy recommendation for your horror anthology and/or vampire fiction shelves.