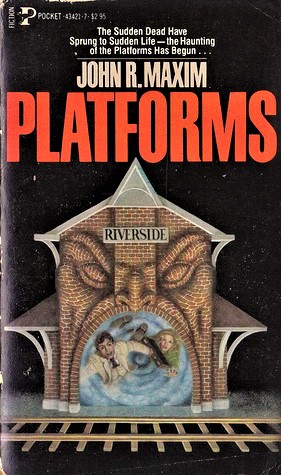

However, its paperback covers offer immediate pleasures for the horror art connoisseur, so let’s just be thankful for that. The uncredited illustration for the 1982 Pocket edition (at top) might be by Lisa Falkenstern, or perhaps Don Ivan Punchatz, depicting business attire-clad commuters sucked into a vortex, is a personal favorite; really great conception and execution of the ominous brick-wall face.

Reprinted for Tor's horror line in 1987, with J.K. Potter art, the book now boasts an eerie tableau of ghostly figures in the artist’s signature photorealistic style. Lastly we have a knockout French edition from 1989, by French artist Matthieu Blanchin. Dig those dark circles around the woman’s eyes—super unsettling! Blanchin did stellar horror covers for the J’ai Lu Épouvante line, most of which rival anything done by American counterparts of the era, I think you’ll agree...Thursday, January 21, 2021

Sudden Dead, Sudden Life

Tuesday, January 19, 2021

Manstopper by Douglas Borton (1988): If Dogs Run Free

Thursday, December 24, 2020

RIP Guy N. Smith (1939 - 2020)

Wednesday, December 23, 2020

Dell Abyss Promo Materials, 1991-1993

Tuesday, December 8, 2020

Horror Fiction Help XXIII

Can anyone help identify these? The first query sounds maddeningly familiar, but damn if I can't quite place it!

1. Late '70s/early '80s: The cover came straight out of Animal Hell, with an illustration of an oversized rat standing on its hind legs, holding the decapitated head of a cat in one hand and gouging its eye out with a bone in the other. Some other vague recollection of the cover includes a pile of bones. I think there also was a little more text on the cover than most books, which leads me to believe it was an anthology of some sort; however I am not positive about this. I remember absolutely nothing about the author(s), title, or back cover. Found! It’s Dr. Rat, 1977 Bantam edition.

2. Unusual horror anthology that came out in the early '60s. It was paperbound, rather thin, and oversize, roughly 2X the dimensions of a paperback. The cover was dark blacks and purples with creepy drawings overlaid (I believe, going from a half century old memory!), and each of the short, 1- to 3-page stories had an illustration with it. Each story had an EC-like twist ending.

3. '90s or early '00s. It was a book of ghost stories, possibly British or Irish. I think there was a story about a banshee, and another about a ghost carrying a coffin and then appearing in an elevator as a warning, but the story I really remember is one where this girl, every birthday, tells her family a man (possibly named Billy, or William) will come for her. Year after year, he doesn't show - until her 18th(?) birthday, when the candles blow out and he appears on a horse and takes her away.

Thursday, November 19, 2020

The Kitty Telefair Gothic Series by Florence Stevenson (1971-1977)

Thursday, October 29, 2020

Favorite Horror Stories: "Shambleau" by Catherine L. Moore (1933)

Featuring a semi-heroic character that Moore would use again and again named Northwest Smith, "Shambleau" at first comes across as standard pulp for its day: Smith is a space pilot, an outlaw, a smuggler, going about business in a kind of Wild West city called Lakkdarol, an outpost on Mars: a raw, red little town where anything might happen, and often did (Smith is obviously a precursor to Han Solo; this type of pulp adventure is just what George Lucas would repurpose for the Star Wars universe).

A wild mob is chasing down a berry-brown girl in a single tattered garment whose scarlet burnt the eyes with its brilliance. Smith draws his laser gun in defense of the poor creature as she evokes a kind of sympathy in him, even though he's no hero. He talks down the mob, who keep shouting "Shambleau!" The leader informs Smith "We never let those things live," but Smith informs him that Shambleau is his, he's keeping her. This puzzles and astonishes the crowd; as they disperse, the leader spits out at Smith: "Keep her then, but don't let her out in this town again!"Obviously relieved, this girl known only as Shambleau cannot speak much English, and Smith is perplexed by the bloodthirsty disgust the mob had evinced towards her. Their brief conversation is halting, but she manages to get out, "Some day I—speak to you—in my own language" (nice foreshadowing!). Smith knows he needs to get her someplace safe, like back to his sparse, rented room. As they walk, he notices others on the streets staring after him and the turban-headed alien girl in disbelief.

Back in his room, Smith tries to get the girl to eat, but she will not. He tells her she can stay safe here, and he goes out to do his business: Smith's errand in Lakkdarol, like most of his errands, is better not spoken of. Man lives as he must, and Smith's living was a perilous affair outside the law and ruled by the ray-gun. He returns that evening, drunk on “segir,” or Martian booze, and is surprised to see Shambleau still there. Yes, he's drunk... and suddenly horny. They embrace...Her velvety arms closed around his neck. And then he was looking down into her face, very near, and the green animal eyes met his with the pulsing pupils and the flicker of—something—deep behind their shallows—and through the rising clamor of his blood, even as he stooped his lips to hers, Smith felt something deep within him shudder away—inexplicable, instinctive, revolted. What it might be he had no words to tell, but the very touch of her was suddenly loathsome—

a lock of scarlet hair fell below the binding leather, hair as scarlet as her garment, as unhumanly red as her eyes were unhumanly green. He stared, and shook his head dizzily and stared again, for it seemed to him that the thick lock of crimson had moved, squirmed of itself against her cheek.

Smith blames this "squirming" on too much too drink, tells the girl to sleep in the corner, and then gets into bed, where he dreams strange dreams beneath a dark Martian night, of some nameless, unthinkable thing ... was coiled about his throat . . . something like a soft snake, wet and warm, sent little thrills of delight through every nerve and fiber of him, a perilous delight. He is like marble, rigid, unable to move, fighting against it, till oblivion takes him and then, bright morning. Dismissing this “devil of a dream,” he tells Shambleau she can stay again, but he'll be leaving Lakkdoral in a day and after that, she'll be on her own.

It was not until late evening, when he turned homeward again, that the thought of the brown girl in his room took definite shape in his mind, though it had been lurking there, formless and submerged, all day. "Formless and submerged," you say? Freud would, as it's said, have had a field day. Shambleau still has not eaten, still speaks in halting English obscurities like "I shall—eat. Before long—I shall—feed. Have no worry." Smith brilliantly asks her if she lives off blood, and she scoffs: "You think me—vampire, eh? No—I am Shambleau!" Well, that clears things up.

That night brings a fuller realization of the horror that is Shambleau, and Moore spares nothing in her efforts to reveal what a danger to the rational human this alien is. Smith wakes to see Shambleau teasing him as she undoes her turban, allowing those scarlet locks to writhe and glisten in an obscene tangle, drawing Smith in helplessly. It's as if he recognizes what she is...

And Smith knew that he looked upon Medusa. The knowledge of that—the realization of vast backgrounds reaching into misted history—shook him out of his frozen horror for a moment, and in that moment he met her eyes again, smiling, green as glass in the moonlight, half hooded under drooping lids. Through the twisting scarlet she held out her arms. And there was something soul-shakingly desirable about her, so that all the blood surged to his head suddenly and he stumbled to his feet like a sleeper in a dream as she swayed toward him, infinitely graceful, infinitely sweet in her cloak of living horror.

Jayem Wilcox’s illustration for Weird Tales

Moore goes on in this amazing pulp fashion, overheated prose all silken seductive slidings, wet and glistening tentacle tresses like serpents, eager and hungry as they crawl towards this man frozen in fear... and desire. As she embraces him, she murmurs, "I shall—speak to you now—in my own tongue—oh, beloved!" Whew. Smith is bewitched, nearly hypnotized, a drug addict now, his identity subsumed into the hungering that Shambleau is, welcoming mindless, deadly bliss.

this mingling of rapture and revulsion all took place in the flashing of a moment while the scarlet worms coiled and crawled upon him, sending deep, obscene tremors of that infinite pleasure into, every atom that made up Smith. And he could not stir in that slimy ecstatic embrace—and a weakness was flooding that grew deeper after each succeeding wave of intense delight, and the traitor in his soul strengthened and drowned out the revulsion—and something within him ceased to struggle as he sank wholly into a blazing darkness that was oblivion to all else but that devouring rapture.

Like the femme fatale of a noir story, Shambleau promises heaven but delivers hell. Only the arrival of a space-pal named Yarol saves Smith; Yarol engages in a last-minute feat of derring-do, as he recognizes the alien for what it is, recalling in him ancient swamp-born memories from Venusian ancestors far away and long ago. Moore concludes her wild tale with the two space friends discussing the origins of Earth myths, an alien race, half-forgotten legends, a race older than man... you know the stuff! Yarol insists that if Smith ever sees a Shambleau again, "You'll draw your gun and burn it to hell."

While horror as a genre is so often concerned with revulsion, fear, despair, and the like, Moore seemed to be clued-in to the uncomfortable fact that horror also can explore forbidden, attractive, addictive desires that polite society deem unacceptable. But as psychologists understand, desire and disgust are rarely opposites; they mingle, coalesce, to beckon us towards our doom... and we’d have it no other way.