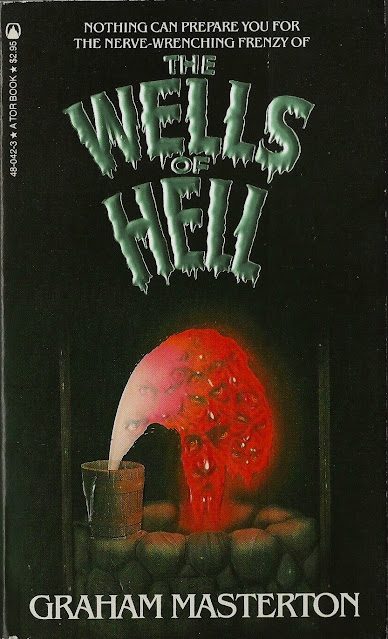

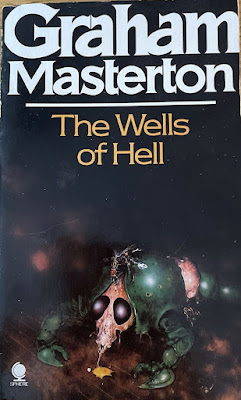

For some time I've been hearing chatter, whether on Facebook or Instagram, Twitter or Reddit, about Masterton's 1979* novel The Wells of Hell, which I believe was his 12th (yep, a dozen novels since his 1975 debut!). Don't know how long I've owned a beat-up copy of the 1982 Tor/Pinnacle edition, which you see at the top there, lackluster cover art by artist unknown, and to be honest I never really gave it much thought till, as I said, hearing chatter about it. Good chatter. (After more than a dozen years running this blog, I've developed a second sense about that kind of thing).

After glumly returning for the fourth or fifth or hundredth time some or other books back to my shelves unread that had failed to impress, that chatter got louder in my head and I plucked Wells from my Masterton collection. Won't say I had high hopes, but I knew I was in good hands—probably.

Aaand—I was! In good hands! Masterton's sure, sarcastic, first-person narration drew me into his tale in an instant, welcoming me back to the fold. Mason Perkins, our narrator, is a humble horror hero, once a college fella studying psychiatry but who dropped out to make a go at something more useful but no less essential when getting to the cause of a problem: plumbing!After some foreshadowing conversation—a missing local child, Jimmy's recent dreams of drowning—Mason takes a sample of the water to his pal Dan Kirk, a scientist working at the town Health Department. There Mason makes cute talk with Dan's assistant, the "provocative" Rheta Warren. Mason delivers the corniest of come-on lines to Rheta—"Is this really a job for a girl like you?"—while Dan looks at the water sample under a microscope. No surprise: swirling through the liquid are tiny seahorse-shaped micro-organisms complete with twisted horns and crusty bodies, excreting a urine-looking substance. Disgusting!

Things take a turn for the worst when, after Dan and Mason go out for dinner and drinks (Rheta has a date with a football player whom Mason mocks like a teenager) and return to the lab to find an unsettling sight: a single mouse, from the crevices of the lab's breakroom, afflicted by a crustacean/insectoid shell and claws on its rear half. They realize it must have drunk from the Bodines' water sample. Mason immediately tries to call the couple to tell them of this alarming development and warn them off the water, but to no avail. The two men make the trek to the Bodines' home, finding it dark, silent, and empty inside, yet dripping with water, as if the house had been submerged in the tide. In an upstairs bedroom, they find the incredible: the body of the Bodines' young son Oliver, impossibly drowned... and in the bath, the chitinous carapace of some kind of enormous insect, crab, or lobster. Disgusting!

Maybe if I put a little dish of butter sauce here with a nutcracker, it will run out the other side.

And, of course, from here more Masterton mayhem. In his classic style of breezy, no-rest-for-the-wicked narrative, he invokes Native mythologies and cosmic Lovecraftian lore as our cast of characters rush to solve the mystery of lobster-shelled locals and flooding waters, missing children and the meaning of "Pontapo's curse." Where are Jimmy and Alison? What lies in the deep crevices beneath the earth of New Milford? What caused the unaccountable drownings of the 1770s? Why is it happening again? Who is Ottauquechee? And last but not least: what the hell is in that well?! I won't spoil it for you, but as one of those creepy monstrosities says:

"I am everything and everyone. I am the servant of the god of times gone by and times yet to be. My name is everything and my face is everyone. I am preparing for the resurrection of the greatest of those who lived beyond the stars... The day will soon be here when the great god will rise out of the wells which have been his sleeping-place for so long, and when all men will bow down before him and offer themselves happily as sacrifice..."

Freaking awesome. There's a headlong sprint to the well-done, eerie subterranean climax, with Shelley (pun intended, one presumes) the cat playing an important role, which should please many readers. Despite his tongue-in-cheek approach, Mason comports himself well for being a simple plumber, bravely facing off with a nightmare nearly beyond comprehension. Wells of Hell may not be the most suspenseful horror novel you'll ever read, as its plot construction is by-the-numbers, and characters even talk about how real life is suddenly feeling a lot like Invasion of the Crab Monsters from the 1950s. But why quibble? This is all good familiar horrific fun.

Masterton has never wasted too much time on the rational understanding of events; his heroes tend to dive in the deep-end with pulp conviction. Nor does he bother making anyone speak American English, they all sound like proper (and not so proper) Britons, but that's part of the Masterton charm. As with his other books, many of which I've enjoyed, there's an almost first-draft vibe; I felt the very ending could've done with another polish. Oh well. Masterton and his Wells of Hell got me out of a summer-long reading slump, I can recommend it to lovers of vintage horror without a second thought, and I can't ask for much more than that!

*The copyright is dated as 1979, but I cannot ascertain which edition was published that year; there is conflicting info online. I know, I know: something wrong on the internet?!