British horror novelist Robert Arthur Smith, born on this date in 1944, produced these paperback originals between 1977 and 1991. He lives in Toronto today but other than that I could find out no real biographical info about him. I own copies of The Prey and Vampire Notes but have not read them; the latter book notes "by the author of The Leopard" but I could find no cover image for that title. The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction says Vampire Notes is "an unusually intricate take on Vampire topoi" and I thought "topoi" was a typo of "topics" till I looked it up and learned it is the plural of a new-to-me, and quite relevant, word! Weird, don't know how that escaped me all these years...

Showing posts with label fawcett gold medal. Show all posts

Showing posts with label fawcett gold medal. Show all posts

Friday, August 23, 2019

Thursday, August 31, 2017

The Legacy by Jere Cunningham (1977): That Demon Life Got Me in Its Sway

You might or might not be familiar with the name Jere Cunningham, a writer who published several horror paperbacks during the classic vintage era but who moved on to Hollywood screenplays later in his career (couldn't turn up a photo of him anywhere, only an illuminating interview, and I'm never sure if the name "Jere" is pronounced "Jare" or like the standard spelling "Jerry"). Not to be confused with that other late 1970s horror paperback of the same title—a novelization of the Katharine Ross/Sam Elliott/uh Roger Daltry movie—Fawcett Gold Medal's The Legacy, with art-student nude-model cover art and a cawing raven 'cause ravens are always spooky, is a 1977 paperback original. Cunningham's not a complete unknown, as other books of his have been rediscovered, but I haven't read any. That could change, since I found The Legacy to be an effective horror read, with all the hallmarks of its day and few of the faults.

A prologue of mysterious import on a stormy night, death, madness, and despair, sets the stage (and not in italics, thank the gods!). Then switch the scene to Dr. David Rawlings, wife Sandra, daughter Melanie, and her Doberman Streak; he's a successful Memphis doctor but as the novel begins he has an upsetting dream about his estranged father one night. Chester Rawlings has died, suicide by gunshot—a-ha, that prologue! Father's lawyer calls David to break the news, maybe they could come to the small Mississippi town of Bickford in which David grew up in but left for med school against Chester's wishes, to where his father met his untimely doom.

Lots of pages are spent on the Rawlings marriage, of Melanie and Streak playing in the fields surrounding the estate, of David tooling around Bickford and realizing what a shithole it is and seeing old faces again. Other characters come into David's orbit: Dewey Pounds, with whom David had played football in high school, now Bickford sheriff well aware if he doesn't solve this issue of a missing body he'll be working in a gas station. There's sketchy teenager Woody, long-haired and resentful, son of Ruth, the local soothsayer living in a trailer and another old friend of Chester's. She drops mysterious hints and warnings, inscrutably vague (basically "You should get the fuck outta Dodge"). Then there is blind Philip Sprague, a man of perhaps 70 who looks younger (uh-oh), who arrived in town some years before and rebuilt a nearby old DeBois manor into a grand new edifice.

The first true note of oddness comes when dad's lawyer Barksdale reads the will and its requirements of David: "I ask that you stay on at Whitewood for seven weeks, never leaving for a single night. Check the seal on the crypt daily. Tend the ivy around the manor and my crypt. I am sure that Sam will stay on with you"—hold up hold up! Did he say check the seal on the crypt?! The fuck? Except Sandy seems to think it an unreasonable burden on David's burgeoning medical practice, but David knows he must do it. Unlike other sons in horror novels, in which family secrets metamorphose into supernatural elements, David loved and respected his father, even if they had grown estranged over his decision to leave.

Exploring his father's library one afternoon, David seemed to feel the hours and hours of his father's presence here. As if the man and years had soaked into the books and walls and floors. Chester Rawlings was a closet intellectual, reading ancient history and philosophy in Latin and Greek. But David is taken aback when he finds a new shelf of books on sorcery and witchcraft and whatnot. There's even a locked door with more spooky shit behind it. Wizard and sorcerer spooky to be precise:

One of the best scenes in the novel is a dinner party, of course. Sprague invites the family to dinner, unerringly pouring them drinks and serving them an elaborate European meal. He is a continental sort and his blindness poses no real problems; in fact it seems to give him a preternatural sense for anyone around him. Après dinner Sprague entices Sandra—whose pretensions to culture and wealth he appeals to—to play for them on his luxurious piano, even joining in with her on his violin. What beautiful music they make ("That was really wonderful," she beamed, hardly able to retain modesty)! And you can be sure David isn't too happy about it. This sequence sets up the finale in high style.

I must admit though that early on, The Legacy had me iffy on continuing; there is a lot of build-up. The narrative tightens up considerably as the book nears conclusion, with occult horror and mayhem rampant, elevating this unassuming-looking paperback original beyond others of its ilk. Cunningham is adept at writing dialogue and character, mood and suspense: aspects horror writers much more famous and wealthy often suck at. Plentiful sex scenes are warm, believable, titillating but restrained. There are touches of early King in the depiction of modern family life while some gruesome set-pieces—David and the dog, David and the corpse fingers, Sandra sleepwalking with Melanie in tow—which reminded me of the work Michael McDowell would soon publish. Despite the leisure taken with setting the story in motion, once it kicks into gear, The Legacy delivers the demonic goods.

A prologue of mysterious import on a stormy night, death, madness, and despair, sets the stage (and not in italics, thank the gods!). Then switch the scene to Dr. David Rawlings, wife Sandra, daughter Melanie, and her Doberman Streak; he's a successful Memphis doctor but as the novel begins he has an upsetting dream about his estranged father one night. Chester Rawlings has died, suicide by gunshot—a-ha, that prologue! Father's lawyer calls David to break the news, maybe they could come to the small Mississippi town of Bickford in which David grew up in but left for med school against Chester's wishes, to where his father met his untimely doom.

You've got the wrong Legacy

He reacquaints himself with the old family estate, Whitewood, and its attendant memories, including old Sam, his father's stalwart friend, who in many ways raised David himself. Sam gets off one of the creepiest lines in the novel, one night when they're trying not to talk about the weirdness going on as they watch the Mississippi beneath a bright moon: "They says if you sleep under the moon without a rag over your face you go moon-crazy. That the moon got blood on it and it'll come down and get in your head." Uh, yeah, thanks for the advice, Sam.Lots of pages are spent on the Rawlings marriage, of Melanie and Streak playing in the fields surrounding the estate, of David tooling around Bickford and realizing what a shithole it is and seeing old faces again. Other characters come into David's orbit: Dewey Pounds, with whom David had played football in high school, now Bickford sheriff well aware if he doesn't solve this issue of a missing body he'll be working in a gas station. There's sketchy teenager Woody, long-haired and resentful, son of Ruth, the local soothsayer living in a trailer and another old friend of Chester's. She drops mysterious hints and warnings, inscrutably vague (basically "You should get the fuck outta Dodge"). Then there is blind Philip Sprague, a man of perhaps 70 who looks younger (uh-oh), who arrived in town some years before and rebuilt a nearby old DeBois manor into a grand new edifice.

The first true note of oddness comes when dad's lawyer Barksdale reads the will and its requirements of David: "I ask that you stay on at Whitewood for seven weeks, never leaving for a single night. Check the seal on the crypt daily. Tend the ivy around the manor and my crypt. I am sure that Sam will stay on with you"—hold up hold up! Did he say check the seal on the crypt?! The fuck? Except Sandy seems to think it an unreasonable burden on David's burgeoning medical practice, but David knows he must do it. Unlike other sons in horror novels, in which family secrets metamorphose into supernatural elements, David loved and respected his father, even if they had grown estranged over his decision to leave.

Exploring his father's library one afternoon, David seemed to feel the hours and hours of his father's presence here. As if the man and years had soaked into the books and walls and floors. Chester Rawlings was a closet intellectual, reading ancient history and philosophy in Latin and Greek. But David is taken aback when he finds a new shelf of books on sorcery and witchcraft and whatnot. There's even a locked door with more spooky shit behind it. Wizard and sorcerer spooky to be precise:

Daddy, he thought, my poor daddy... is that what happened in your mind? Did fantasies kill you? Don't you know that one real cigarette is more evil than all that silly occult shit put together?... A foulness clung to his hands from the cloying leather. in the light the stretched hide looked almost like human epidermis... He left the room with a sadness tainted by revulsion. Never would he have dreamed his father—of all people—would have sought solace or refuge in an area so degrading in its vulgar absurdity. The foulness of the iron-bound book felt ugly on his hands.

Sphere Books UK paperback, 1980

I don't have to tell you, dedicated reader of horror fiction, how important this is. This kind of exploration and discovery is one of my favorite genre devices. And Cunningham deploys it well; a foreshadowing that hovers even though it will be quite awhile before the payoff. Slowly but surely all kinds of horrible things will happen: a missing corpse, a vandalized crypt, a dead friend, Sandra sleepwalking, a figure following Melanie and Streak through the nearby woods. Add in a backstory of the recent suicide of a Bickford banker, the institutionalization of his wife, and the disappearance of their young daughter, and you've got a sweet potboiler recipe.

Eventually David finds his father's journal and learns Chester knew Sprague, also dined with him, was taken on a tour of the manor's foundation, and there saw something that drove him to near madness, breaking his heart and setting Chester into a morass of despair.

Now I am considering the murder of Sprague. Or the end of myself. No night of rest.... I spoke with Ruth. She is more afraid than I am, if that is possible, and she knows nothing we can do. What can we say about the little girl? What would the authorities believe? That we are mad?

Cunningham's 1982 novel, UK paperback

One of the best scenes in the novel is a dinner party, of course. Sprague invites the family to dinner, unerringly pouring them drinks and serving them an elaborate European meal. He is a continental sort and his blindness poses no real problems; in fact it seems to give him a preternatural sense for anyone around him. Après dinner Sprague entices Sandra—whose pretensions to culture and wealth he appeals to—to play for them on his luxurious piano, even joining in with her on his violin. What beautiful music they make ("That was really wonderful," she beamed, hardly able to retain modesty)! And you can be sure David isn't too happy about it. This sequence sets up the finale in high style.

I must admit though that early on, The Legacy had me iffy on continuing; there is a lot of build-up. The narrative tightens up considerably as the book nears conclusion, with occult horror and mayhem rampant, elevating this unassuming-looking paperback original beyond others of its ilk. Cunningham is adept at writing dialogue and character, mood and suspense: aspects horror writers much more famous and wealthy often suck at. Plentiful sex scenes are warm, believable, titillating but restrained. There are touches of early King in the depiction of modern family life while some gruesome set-pieces—David and the dog, David and the corpse fingers, Sandra sleepwalking with Melanie in tow—which reminded me of the work Michael McDowell would soon publish. Despite the leisure taken with setting the story in motion, once it kicks into gear, The Legacy delivers the demonic goods.

Cernunnos, Lord of my Fathers, Lord of Ages, I summon thee. Lord of Agonies, of Carthage and Hiroshima and Doomed Great Ones, I summon thee to wed and to sup. Rise from thy eternal legions and I shall perform thy shapely introduction as ages ago I vowed in time upon time upon time to fulfill...

Sunday, May 31, 2015

Gary Brandner Born Today, 1933

Best known as the author of The Howling werewolf series, Gary Brandner wrote a good handful of 1980s horror novels published by Fawcett Gold Medal. These have got to be some of the lamest covers of that era (except, of course, his Cat People novelization, which is the movie poster image anyway)! Brandner died in 2013.

Sunday, June 15, 2014

Gwen, in Green by Hugh Zachary (1974): Every Time I Eat Vegetables It Makes Me Think of You

Is erotic eco-horror a thing? I'm trying to think...

One of my favorite paperback covers since I first came across it on one website or another, George Ziel's sensual, provocative, darkly luscious art here strikes a potential reader immediately. Who can penetrate the mystery of this woman's skyward gaze, full of awe and perhaps understanding, in thrall to some mysterious force, naked and exposed to the swamp flora crawling up her flesh as if claiming her for its own purposes? Fortunately, author Hugh Zachary is up to the task of solving this mystery; and Gwen, in Green (Fawcett Gold Medal, July 1974) is a quiet and bewitching little work that provides a bit of sexy '70s fun and fright. Ziel's cover perfectly captures the tone and texture of Zachary's tale - and you know what a special treat it is when cover art and content align in harmony.

One of my favorite paperback covers since I first came across it on one website or another, George Ziel's sensual, provocative, darkly luscious art here strikes a potential reader immediately. Who can penetrate the mystery of this woman's skyward gaze, full of awe and perhaps understanding, in thrall to some mysterious force, naked and exposed to the swamp flora crawling up her flesh as if claiming her for its own purposes? Fortunately, author Hugh Zachary is up to the task of solving this mystery; and Gwen, in Green (Fawcett Gold Medal, July 1974) is a quiet and bewitching little work that provides a bit of sexy '70s fun and fright. Ziel's cover perfectly captures the tone and texture of Zachary's tale - and you know what a special treat it is when cover art and content align in harmony.

Zachary in late Sixties

Some spoilers ahead. The back cover gives the basics. Our lovely Gwen has been married to electrical engineer George Ferrier for seven years when the story begins. After coming into family money, he's just bought a plot undeveloped land on an island on the Cape Fear River; nearby a nuclear power plant is being built (George's research shows the danger of radioactivity is, apparently, nil). So in come the developers, earth movers, bulldozers, and crewmen to clear away the swamp and brush and undergrowth and build the Ferriers' new home. Here they indulge in a full and healthy sex life (a large part of the novel which Zachary delights in) but Gwen, whose childhood was one of misfortune and neglect, still feels twinges of shame and guilt: her widowed mother was a loose woman

who wasn't careful about keeping the bedroom door closed.

A complex grew, encouraged by the teasing by Gwen's schoolmates, and so

as an adult Gwen considers herself a prude, a nut - in the parlance of

the day, frigid.

But gentle and patient he-man paramour George has coaxed Gwen into experiencing much sexual pleasure (no way this modern man's wife is gonna be frigid! All she needs is a real man's touch seems to be his motto):

And so it goes. Husband and wife now engage in playful banter (which of course includes some rape references that will bemuse today's reader) and a newfound happiness. Gwen begins painting trees and caring for lush African violets, and becomes enamored of the Venus fly-trap plants she finds at a nearby lake and begins feeding raw hamburger. But creeping into this domestic bliss are her nightmares: the mass roared down on her, huge teeth snapping at her. The mouth closed, clashing metal teeth, and she screamed once before she felt the tender flesh being punctured and rendered. Her upper body fell, being ripped from her legs and stomach and hips...

But gentle and patient he-man paramour George has coaxed Gwen into experiencing much sexual pleasure (no way this modern man's wife is gonna be frigid! All she needs is a real man's touch seems to be his motto):

She lay in total darkness, limply submitting to his touch, his obscene kiss, his fast, labored breathing. And her clitoris swelled. A tendril of something went shooting down, down, centered there. She jerked her eyes open, shocked. A stiffening in her legs, an almost imperceptible lifting of her loins... She found that certain body movements are instinctive.

And so it goes. Husband and wife now engage in playful banter (which of course includes some rape references that will bemuse today's reader) and a newfound happiness. Gwen begins painting trees and caring for lush African violets, and becomes enamored of the Venus fly-trap plants she finds at a nearby lake and begins feeding raw hamburger. But creeping into this domestic bliss are her nightmares: the mass roared down on her, huge teeth snapping at her. The mouth closed, clashing metal teeth, and she screamed once before she felt the tender flesh being punctured and rendered. Her upper body fell, being ripped from her legs and stomach and hips...

These dreams continue till one afternoon while George is at work, Gwen seduces a meter reader. Yep, you read right; the classic porn scenario. It's rather an out-of-body experience for Gwen, and she's shocked and mortified by the physical act she's shared with a stranger.

This is some serious '70s softcore! Sadly a suicide attempt is next. George and their doctor set her up with elderly psychiatrist Dr. Irving King - a Freudian by training, who had developed some rather independent ideas in thirty-five years of practice in an area of the country where psychiatry was not fully understood - and the required questioning begins, and we can begin to fathom Gwen's disordered mind. "Have you ever killed anything, Gwen?" "No. Oh, insects. Plants." "Plants?" "Isn't that silly?" And off we go! Gwen is slowly but surely identifying, in her mind, with the flora all about her on their spot of land, the Venus fly-traps, the African violets, the giant trees, the slimy green things beneath the water - all of which are being torn asunder by the developers and even her husband. Gwen feels mad, invaded, but by what? The painful dreams continue... and so do the illicit trysts. Only sex can ease the horrific sensation of dismemberment. Happy George has no idea that his wanton, sexy, endlessly hungry woman is truly not herself any longer.

And so sex and death commence to commingle. The men who drive the bulldozers come one by one to Gwen (sometimes not even one by one). They don't return to drive the bulldozers. Dr. King suspects, researches, finds, confronts. We get a crazy, nutty explanation for Gwen's "possession" that could be real or could be her own sexual, perhaps even maternal, guilt turning round on her and eating her up. Zachary hints one way, then the other, then the tale ends as the sharp reader will have predicted. It couldn't go any other way, and do I love doomy downward spirals. She continued to chop, breathing in sobbing agony. The strap to her bikini top had broken. The small scrap of material hung from her neck, flapping with her movements. Water and perspiration and blood beaded her lower legs.

I found Gwen to be a mild and relaxing read; nothing earth-shattering, but confidently written and just odd enough (and oh-so-'70s enough) to keep me reading happily. I liked the cozy, isolated forested locale; Zachary puts in

lots of detail about how rewarding working your own land is. Characters have specific natures and interior thoughts that ring true. The plentiful sex scenes were done well, Zachary knowing when to be graphic and when to leave us to fill in the blanks. Even Gwen's dalliances with teen boys were more hilariously dated than

ickily offensive (again, the anything-goes vibe of the '70s !). The

sexism that pops up in the book raises a chuckle and can be forgiven; after their first meeting, Dr. King says to Gwen, "You are much too pretty to be eaten by nightmare things," or when she tells George her bizarre dreams and he chides her, "You are one spooky broad." And yes, good death scenes that have bite, reminding me some of Michael

McDowell: a nice leisurely story carrying you along then boom, a short

sharp shock of violence.

Postscript: Some background on what surely inspired the novel. In 1973 the nonfiction book The Secret Life of Plants was first published. A bestselling and highly popular book of its day, it even became a film documentary (with a soundtrack by Stevie Wonder!). However it was speculative pseudoscience, appealing to hippies and to folks amenable to proto-New Age ideals filtering into the mainstream, swept along in the same current as astrology, crystal healing powers, and the lost continent of Mu. Secret Life's bubble-headed thesis was that plants have sentience and emotion, even telepathic powers, all girded by laughable "scientific" "experiments" like attaching polygraph electrodes to plant leaves. I know, I know! Whether he meant to satirize the theory or not, Zachary uses it as the launching pad for Gwen. In horror fiction, that sort of nonsense is a plus. Had I not worked in a used bookstore in the late 1980s and saw old copies of Secret Life, I wouldn't have been aware of it as the novel's impetus. It won't really affect your enjoyment of Gwen, but I myself dig the dated context.

She held her arms out, smiling. No question of morality. No right. No wrong. It was the way things were. Fertile, ripe, passive, she accepted him, eased his fevered haste, and bathed him in the sweet juices of her body.

1976 Coronet UK w/ art by Jim Burns

(I blacked out spoiler tagline)

This is some serious '70s softcore! Sadly a suicide attempt is next. George and their doctor set her up with elderly psychiatrist Dr. Irving King - a Freudian by training, who had developed some rather independent ideas in thirty-five years of practice in an area of the country where psychiatry was not fully understood - and the required questioning begins, and we can begin to fathom Gwen's disordered mind. "Have you ever killed anything, Gwen?" "No. Oh, insects. Plants." "Plants?" "Isn't that silly?" And off we go! Gwen is slowly but surely identifying, in her mind, with the flora all about her on their spot of land, the Venus fly-traps, the African violets, the giant trees, the slimy green things beneath the water - all of which are being torn asunder by the developers and even her husband. Gwen feels mad, invaded, but by what? The painful dreams continue... and so do the illicit trysts. Only sex can ease the horrific sensation of dismemberment. Happy George has no idea that his wanton, sexy, endlessly hungry woman is truly not herself any longer.

And so sex and death commence to commingle. The men who drive the bulldozers come one by one to Gwen (sometimes not even one by one). They don't return to drive the bulldozers. Dr. King suspects, researches, finds, confronts. We get a crazy, nutty explanation for Gwen's "possession" that could be real or could be her own sexual, perhaps even maternal, guilt turning round on her and eating her up. Zachary hints one way, then the other, then the tale ends as the sharp reader will have predicted. It couldn't go any other way, and do I love doomy downward spirals. She continued to chop, breathing in sobbing agony. The strap to her bikini top had broken. The small scrap of material hung from her neck, flapping with her movements. Water and perspiration and blood beaded her lower legs.

Zachary wrote under pseudonym Zach Hughes. Dig Tide 1975!

Gwen, in Green, is a satisfying work of smart, fun, pulp horror that could only have been written in the early 1970s. Which is one of my highest compliments! Find a copy, admire its magnificent cover, and read while sipping a gin & tonic under the summer sun near a crystal-clear lake beneath towering, creeping greenery. Shouldn't take you more than an afternoon or two to read it, but you just might feel differently about that vegetation when you're done.

Postscript: Some background on what surely inspired the novel. In 1973 the nonfiction book The Secret Life of Plants was first published. A bestselling and highly popular book of its day, it even became a film documentary (with a soundtrack by Stevie Wonder!). However it was speculative pseudoscience, appealing to hippies and to folks amenable to proto-New Age ideals filtering into the mainstream, swept along in the same current as astrology, crystal healing powers, and the lost continent of Mu. Secret Life's bubble-headed thesis was that plants have sentience and emotion, even telepathic powers, all girded by laughable "scientific" "experiments" like attaching polygraph electrodes to plant leaves. I know, I know! Whether he meant to satirize the theory or not, Zachary uses it as the launching pad for Gwen. In horror fiction, that sort of nonsense is a plus. Had I not worked in a used bookstore in the late 1980s and saw old copies of Secret Life, I wouldn't have been aware of it as the novel's impetus. It won't really affect your enjoyment of Gwen, but I myself dig the dated context.

Sunday, July 28, 2013

The Howling by Gary Brandner (1977): Don't Scratch At No Doors

Mostly by-the-numbers horror tale featuring vaguely described werewolves, The Howling at least revived the long-dormant lycanthrope trope and let it loose into the modern world via its unfaithful yet awesomely fun 1981 film adaptation. And while Gary Brandner's paperback original (Fawcett World Library, 1977) isn't as blood-and-guts gory as one might think, it doesn't stint on graphic sex. Its opening rape scene is tawdry in the extreme but at least Brandner can write okay, nothing special but not terrible either. Appreciate the fact that The Howling is not overly long, moves quickly, is lean and sometimes mean.

One bothersome trait: he kept referring to the werewolves as simply wolves - like Benchley in Jaws, repeatedly referring to his monstrous Carcharodon carcharias as simply a fish - which I found distinctly underwhelming (I have always thought of werewolves as having both human and wolf physical characteristics). The transformation sequence doesn't shock or surprise, gets the job done, and simply underlines the point that werewolf stories are best told in images and not in prose. I mean we all remember Cycle of the Werewolf, right?

What the novel does have going for it is a powerful vein of erotic abandonment (which fortunately did make it into the movie), something I don't think had been seen much in werewolf stories prior. There are several sequels too. And check out Brandner's interview in Dark Dreamers, in which he relates the sad, frustrating, rewardless travails of trying to write werewolf stories for Hollywood. But I must mention Whitley Strieber's Wolfen or Thomas Tessier's The Nightwalker for those interested in really provocative, well-written, thoughtful wolf tales. The Howling is pulp horror through and through - and it's not, I probably don't have to tell you, in any way, shapeshift or form, in the tradition of 'Salem's Lot whatsoever.

1978 UK paperback

One bothersome trait: he kept referring to the werewolves as simply wolves - like Benchley in Jaws, repeatedly referring to his monstrous Carcharodon carcharias as simply a fish - which I found distinctly underwhelming (I have always thought of werewolves as having both human and wolf physical characteristics). The transformation sequence doesn't shock or surprise, gets the job done, and simply underlines the point that werewolf stories are best told in images and not in prose. I mean we all remember Cycle of the Werewolf, right?

What the novel does have going for it is a powerful vein of erotic abandonment (which fortunately did make it into the movie), something I don't think had been seen much in werewolf stories prior. There are several sequels too. And check out Brandner's interview in Dark Dreamers, in which he relates the sad, frustrating, rewardless travails of trying to write werewolf stories for Hollywood. But I must mention Whitley Strieber's Wolfen or Thomas Tessier's The Nightwalker for those interested in really provocative, well-written, thoughtful wolf tales. The Howling is pulp horror through and through - and it's not, I probably don't have to tell you, in any way, shapeshift or form, in the tradition of 'Salem's Lot whatsoever.

Friday, April 27, 2012

Fawcett Horror Paperbacks of the 1980s

By

the early 1980s, Fawcett seemed to have moved on from the moody,

studied paperback cover art they used in the 1970s. Perhaps the growing

horror field of the new decade gave them more competition and those books didn't sell

as well any longer. Perhaps talented artists who worked in paints and canvases and good old-fashioned suggestive spookiness were too expensive. These covers are simpler, more direct, not as

impressive, and in a couple cases just corny, tasteless without being

quite ridiculous enough for a laugh. The three volumes in The Howling

series, Gary Brandner's werewolf saga, (1977/1981/1985 respectively)

utilize the same monstery font and stylization; I do kinda like the "one

fang/two fangs/three fangs" motif.

When Paul Schrader remade the 1940s classic B&W Val Lewton horror film Cat People in 1982, Brandner wrote the novelization. Sure, this cover has the same image as the movie poster, but what an image! Truly one of my favorite horror ladies of all time.

Killing Eyes, John Miglis (1983) Yikes. I mean, look away! Those eyes are so unsettling, I missed the bullet hole first time I saw this cover.

The Boogeyman, B.W. Battin (1983) This kind of simplicity actually works: the child's scawl, the bloody fingerprint that looks almost real...

The Beast, Walter J. Sheldon (1980) Move along, nothing to see here folks.

Falling Angel, William Hjortsberg (1978) - Yeah, it's from '78, but I'm throwing this in as a freebie. I've featured this cover before, in my review; it's absolutely one of my favorite books that I've read for this site! I even sent an effusive fan email to Hjortsberg a month or two ago (drinking and the internets don't mix), but luckily received an appreciative reply. Whew.

When Paul Schrader remade the 1940s classic B&W Val Lewton horror film Cat People in 1982, Brandner wrote the novelization. Sure, this cover has the same image as the movie poster, but what an image! Truly one of my favorite horror ladies of all time.

Vampire Notes (1989) and The Keeper (1986), Robert Arthur Smith. No idea who Smith is, but he got some of the better '80s covers from Fawcett.

The Boogeyman, B.W. Battin (1983) This kind of simplicity actually works: the child's scawl, the bloody fingerprint that looks almost real...

The Beast, Walter J. Sheldon (1980) Move along, nothing to see here folks.

Death Sleep, Jerry Sohl (1983) He sure sounds like Freddy Krueger...

Wednesday, April 25, 2012

Fawcett Horror Paperbacks of the 1970s

Thanks to the incomparable bibliographic efforts of both The Paperback Fanatic and The Vault of Evil, I'm able to feature a mere morsel of the strangely tasteful yet effective paperback covers featured on horror/thriller novels published several decades ago by Fawcett, which includes Fawcett Crest and Fawcett Gold Medal imprints. So many skilled, eerie, beautifully specific paintings, evoking in us the ghostly chill of mere shadows and gloom... and making you realize how much most paperback horror covers today suck. Hauntings by Norah Lofts (1977) above, the creepy old crone, glaring owl, and robed figure make for a wonderfully gothic horror cover, even if it is all painted in gold.

American Gothic, Robert Bloch (1974). Ah, yes, By the author of Psycho, the ever-present quote. That dark figure following... looks a bit like Bloch's other fave psycho, that Saucy Jack!

Leviathan, John Gordon Davis (1977) Really really great cover in the style of Jaws.

The Night Creature, Brian Ball (1974) A perfectly reductive horror title, and such an evocative macabre piece of cover art, darkly unfocused except for that look of paralyzed fright.

American Gothic, Robert Bloch (1974). Ah, yes, By the author of Psycho, the ever-present quote. That dark figure following... looks a bit like Bloch's other fave psycho, that Saucy Jack!

Leviathan, John Gordon Davis (1977) Really really great cover in the style of Jaws.

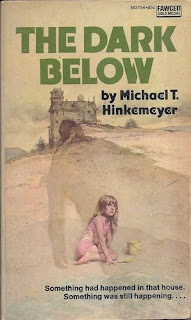

The Dark Below, Michael Hinkemeyer (1975) Love the contrast between title and cream-colored cover art. Veeerrry menacing.

The Running of the Beasts, Bill Pronzini and Barry Malzberg (1976) I've heard good stuff about this thriller... gotta love the reflection of the woman in the knife. Well, I suppose you don't gotta, but I do.The Night Creature, Brian Ball (1974) A perfectly reductive horror title, and such an evocative macabre piece of cover art, darkly unfocused except for that look of paralyzed fright.

Monday, January 2, 2012

Charles Beaumont Born Today 1929

Born today in the barely conceivable year of 1929, Charles Beaumont is one of the forgotten figures in horror/science fiction/fantasy. Well, not at Too Much Horror Fiction! I originally featured Beaumont here. You can also watch his many episodes of "The Twilight Zone" on Netflix Instant. You ever find one of his vintage paperbacks in a used bookstore, buy it. I've got a few, but not these (Yonder, a collection from 1958, is especially desired):

Tuesday, August 9, 2011

Gwen, in Green by Hugh Zachary (1974) and a Personal Update

Gorgeous, gorgeous, utterly gorgeous cover art (artist unknown, alas - *update: it's actually George Ziel) for a novel I've only recently found out about, a sort of fantasy-horror about evil and mind-controlling plants. I love everything about it, and don't you? Gwen, in Green you can be sure has been added to my must-have list! Read a review here, which features the UK paperback.

Gorgeous, gorgeous, utterly gorgeous cover art (artist unknown, alas - *update: it's actually George Ziel) for a novel I've only recently found out about, a sort of fantasy-horror about evil and mind-controlling plants. I love everything about it, and don't you? Gwen, in Green you can be sure has been added to my must-have list! Read a review here, which features the UK paperback. Speaking of my must-have list: this past weekend I took a mini-vacation up to my hometown in South Jersey and was able to visit that used bookstore I worked at in the early '90s, now called Bogart's Books. Armed with that list, and with the memories of many vintage-era horror "classics" on the shelves, I went in Friday morning and... bought nearly 20 paperback horror novels!

Speaking of my must-have list: this past weekend I took a mini-vacation up to my hometown in South Jersey and was able to visit that used bookstore I worked at in the early '90s, now called Bogart's Books. Armed with that list, and with the memories of many vintage-era horror "classics" on the shelves, I went in Friday morning and... bought nearly 20 paperback horror novels! I couldn't believe the stuff I found, couldn't even afford to buy everything I wanted. Some stuff I wanted but didn't buy because it was in poor shape - Skipp and Spector's The Cleanup, Strieber's The Hunger, Leiber's Night's Black Agents - but what I did pick up will keep this site in good stead for some time. There is Masterton and Garton and Wright and Etchison and Hodge and Rice and more, much more. Hell, I even snagged a copy of John McCarty's essential and completely thorough Splatter Movies: Breaking the Last Taboo of the Screen, from 1984 (cover image from Blue Eyes of the Broken Doll).

I couldn't believe the stuff I found, couldn't even afford to buy everything I wanted. Some stuff I wanted but didn't buy because it was in poor shape - Skipp and Spector's The Cleanup, Strieber's The Hunger, Leiber's Night's Black Agents - but what I did pick up will keep this site in good stead for some time. There is Masterton and Garton and Wright and Etchison and Hodge and Rice and more, much more. Hell, I even snagged a copy of John McCarty's essential and completely thorough Splatter Movies: Breaking the Last Taboo of the Screen, from 1984 (cover image from Blue Eyes of the Broken Doll). Also, my girlfriend is on her own little vacation and stopped in at the famous Powell's City of Books in Portland, OR, and called to say she'd found a few gems for me, some Grant, Matheson, and F. Paul Wilson, as I recall. Lucky me!

Also, my girlfriend is on her own little vacation and stopped in at the famous Powell's City of Books in Portland, OR, and called to say she'd found a few gems for me, some Grant, Matheson, and F. Paul Wilson, as I recall. Lucky me! And on a personal note, I probably haven't mentioned it here but I've been laid off so far this entire year... till this week. Now that I'm back to full-time work I'm not sure if I'll be updating Too Much Horror Fiction as often as I have been. But I always make time to read - in fact, I don't even have to make time to read; I just read, and always have - and now I've got more than a dozen novels added to my shelves and to-read list. Oh well, I wouldn't have it any other way!

And on a personal note, I probably haven't mentioned it here but I've been laid off so far this entire year... till this week. Now that I'm back to full-time work I'm not sure if I'll be updating Too Much Horror Fiction as often as I have been. But I always make time to read - in fact, I don't even have to make time to read; I just read, and always have - and now I've got more than a dozen novels added to my shelves and to-read list. Oh well, I wouldn't have it any other way!

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)