Valancourt hopes to have it ready to go by year's end. And Valancourt, Grady Hendrix, and I are still hoping to bring you more of these. For all information on ordering and whatnot, go here. For more on this series, go here.

Showing posts with label george ziel. Show all posts

Showing posts with label george ziel. Show all posts

Tuesday, August 10, 2021

Latest Title in Valancourt's Paperbacks from Hell Series: Gwen, in Green!

Great news, everyone! The series of reprints of classic titles featured in Paperbacks from Hell from Valancourt Books is not over—coming next is the 1974 eco-horror novel Gwen, in Green, by Hugh Zachary. The book will feature the stunning George Ziel cover art from the Fawcett Gold Medal edition; I will be writing the introduction for it. This is a personal favorite of mine and I lobbied hard to get it back in print, while the guys at Valancourt diligently tracked down the late Zachary's estate to obtain the rights. The process seemed to take forever, but here we are!

Wednesday, October 30, 2019

False Idols by Betty Ferm (1974): A Demon Needs a Maid

Remember that scene in 1979's Love at First Bite in which Richard

Benjamin, the Van Helsing character, attempts to thwart George

Hamilton's Dracula by pulling a crucifix from his pocket—but mistakenly

takes out a Star of David?

When I saw the movie as a kid I didn't get the joke, but it's a good

one. Jewish-themed horror is, alas, the tiniest of subgenres in vintage

horror fiction, and it can be done well (or, like anything else, not well), but I don't think it's been done enough. This explains why I was intrigued by this back cover copy hinting at a Jewish,

rather than a typical Christian, origin for the otherworldly horrors and chilling premonitions promised here. Alas, there's not much going on, Jewish or otherwise, in False Idols (Fawcett Crest paperback, June 1975), a 1974 supernatural thriller that fails to thrill or do anything much at all. False is right.

Everything is leftover Levin and Blatty: the dash of social concern, a whiff of current mores, but nothing goes deep. Familiar elements are all-too-smoothly cobbled together from those better works, from Dark Shadows, soaps, TV movies, commercials, et al. (Similar contemporaneous novels by Ramona Stewart and Barbara Michaels are smarter and spookier too). The upper middle-class setting is bland and rote, and no ethnic flavor is to be found to give the novel its own identity. Our tale goes from bad to worse as soon as Fran, our beleaguered protag, leaves the home to return to the work she left behind once married, and it's the South American maids with their "almond eyes" and "faint musky scent" who cause all the demonic trouble. It's hard to get good help these days!

Mezuzahs replace crosses and the terrified old mother-in-laws shrieks about the Dybbuk, some Jewish grieving practices are only slotted in, that's all, surface details only. The possessive demon hails from Mesoamerican Incan mythology: Taguapica by name, and boy does he have it in for the Old Testament God: "Look around you, Yahweh. Your world is dead as you are dead to the world. It is Taguapica who will reign now" he bellows in the overheated climax. It's the kind of comparative religions scenario Graham Masterton would crank up to 11 in just a few short years. Maybe the novel had some effect for readers in its era as a decent enough time-waster, but nearly half a century later False Idols is simply a dull, unremarkable artifact from a bygone age.

Everything is leftover Levin and Blatty: the dash of social concern, a whiff of current mores, but nothing goes deep. Familiar elements are all-too-smoothly cobbled together from those better works, from Dark Shadows, soaps, TV movies, commercials, et al. (Similar contemporaneous novels by Ramona Stewart and Barbara Michaels are smarter and spookier too). The upper middle-class setting is bland and rote, and no ethnic flavor is to be found to give the novel its own identity. Our tale goes from bad to worse as soon as Fran, our beleaguered protag, leaves the home to return to the work she left behind once married, and it's the South American maids with their "almond eyes" and "faint musky scent" who cause all the demonic trouble. It's hard to get good help these days!

Mezuzahs replace crosses and the terrified old mother-in-laws shrieks about the Dybbuk, some Jewish grieving practices are only slotted in, that's all, surface details only. The possessive demon hails from Mesoamerican Incan mythology: Taguapica by name, and boy does he have it in for the Old Testament God: "Look around you, Yahweh. Your world is dead as you are dead to the world. It is Taguapica who will reign now" he bellows in the overheated climax. It's the kind of comparative religions scenario Graham Masterton would crank up to 11 in just a few short years. Maybe the novel had some effect for readers in its era as a decent enough time-waster, but nearly half a century later False Idols is simply a dull, unremarkable artifact from a bygone age.

Putnam hardcover, 1974

Psychiatrist Livvy Webber—the kind of smart, helpful, good-hearted character you just know is toast sooner or later—actually says at one point early in the novel that "Each time a Rosemary's Baby or an Exorcist hits the market I can be guaranteed a number of new patients who lay claim to related phenomena as the cause for the fouled-up lives." More of this contemporary self-awareness would have given a fresh coat of paint to our tired tale, which lasts a scant 174 pages. The ending is not an ending, it's all still going on, you know how it goes.

Speaking of coats of paint, at least the paperback offers up eerie cover art thanks to the masterful George Ziel, although the lusty, brazen, confident lady in red never—sadly—makes an appearance.

Author Betty Ferm (1926-2019) wrote nearly a dozen novels in various popular genres (see some below) and taught college courses in writing suspense novels.

Friday, August 31, 2018

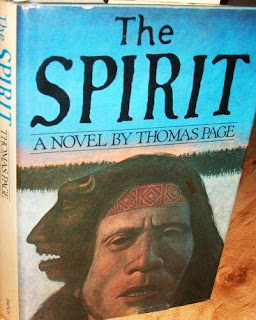

The Spirit by Thomas Page (1977): You Drive Me Ape You Big Gorilla

Bigfoot was big news throughout the 1970s, thanks to that infamous Patterson footage of the late 1960s. Stomping across the pop cultural landscape and metal-and-asphalt playgrounds of the decade, he showed up on TV ("Bigfoot and Wildboy"! "In Search of..."! "The Six Million Dollar Man"!) and in some cheapie movies I recall older relatives and brothers of friends going to see. Even the commercials and specials on TV terrified me. Amongst the drugstore spinner racks that held our precious horror paperbacks readers could also find "non-fiction" on Sasquatch, and the covers offer that same fine vintage frisson.

Berkley Books, 1977, rare collectible

Er, no thanks, I'm good

But Bigfoot was dead and gone by the '80s—I was just too old for 1987's Harry and the Hendersons—and although he's back in a big way today, I can't say I have any interest in him. So it was with some measure of "meh" that I approached The Spirit, a 1977 novel actually published in hardcover (scroll down for cover). Ballantine released the paperback edition in 1978 with a moody George Ziel cover, as he does so well, and I was sort of expecting an adventure-romance tinged with creature horror. Author Thomas Page (b. 1942, Washington DC) wrote a few other genre paperbacks in the day that I've seen here and there over the years but I know nothing about him. I do know he can spin a yarn and mix in some solid suspense and a few snatches of 'Squatch destruction.

There is something I think distasteful about implying Bigfoot is dangerous to humans, I've always felt, but now I see he is generally part of the "eco-horror" moment of that era, when the natural world has simply had enough of humans trashing it for big bucks and fights back by any means necessary. Bigfoot simply does not respond well to ski resorts in his 'hood! Page's novel, despite the slavering back-cover copy and its swooning-romance cover, is more tasteful than those pulp implications, as its specific horror elements are minimal and there is no romantic element whatsoever, which is a shame because two characters meet cute and I could've done with some sexy Seventies sex action.

Still, I do think Spirit is a rewarding little read for those who dig the 'foot, as it has some terrific action setpieces and opens with a harrowing helicopter crash, characters and dialogue aren't a lot more than stock but serve adequate purpose for the story. Page isn't too shabby at mixing in Native American lore either, adding a dash of the hallucinating Vietnam vet and the vision quest, and has some fun theorizing on the anthropological origins of the creature (genetic deformity? cross-species banging?), thanks to our manly-man protagonist's visits to a primate specialist. Bigfoot sightings aren't overdone and have a bit of subtlety about them—She had materialized from the forest, as massive as a mountain and light as a wraith—but definitely convey the creatures' power and might. There's even sad note of irony at the end.

But only dum-dum Lester, who works in the ski lodge kitchen and knows what he saw that one eerie night even though everyone thinks he made it up and he tries to recant even though he really wants to make some money off it on the Johnny Carson show, truly knows what's up with the 'Squatch:

1977 US hardcover, Rawson Associates

Easily the most accurate cover art

Still, I do think Spirit is a rewarding little read for those who dig the 'foot, as it has some terrific action setpieces and opens with a harrowing helicopter crash, characters and dialogue aren't a lot more than stock but serve adequate purpose for the story. Page isn't too shabby at mixing in Native American lore either, adding a dash of the hallucinating Vietnam vet and the vision quest, and has some fun theorizing on the anthropological origins of the creature (genetic deformity? cross-species banging?), thanks to our manly-man protagonist's visits to a primate specialist. Bigfoot sightings aren't overdone and have a bit of subtlety about them—She had materialized from the forest, as massive as a mountain and light as a wraith—but definitely convey the creatures' power and might. There's even sad note of irony at the end.

1979 Hamlyn UK paperback

But only dum-dum Lester, who works in the ski lodge kitchen and knows what he saw that one eerie night even though everyone thinks he made it up and he tries to recant even though he really wants to make some money off it on the Johnny Carson show, truly knows what's up with the 'Squatch:

Somebody once said on a late-night TV show that people were afraid of the full moon because thousands of years ago the earth was covered with different types of humans who came out then. These humans lived in the woods with saber-toothed tigers and snakes and dinosaurs and mastodons, and got along great with them because they all ate the same thing: other humans.

Berkley Books, 1977, rare collectible

Er, no thanks, I'm good

Saturday, March 28, 2015

Cat Sound!

Another cover lovely from the untouchable George Ziel (born on this date in 1914). Cat sound indeed.

Sunday, June 15, 2014

Gwen, in Green by Hugh Zachary (1974): Every Time I Eat Vegetables It Makes Me Think of You

Is erotic eco-horror a thing? I'm trying to think...

One of my favorite paperback covers since I first came across it on one website or another, George Ziel's sensual, provocative, darkly luscious art here strikes a potential reader immediately. Who can penetrate the mystery of this woman's skyward gaze, full of awe and perhaps understanding, in thrall to some mysterious force, naked and exposed to the swamp flora crawling up her flesh as if claiming her for its own purposes? Fortunately, author Hugh Zachary is up to the task of solving this mystery; and Gwen, in Green (Fawcett Gold Medal, July 1974) is a quiet and bewitching little work that provides a bit of sexy '70s fun and fright. Ziel's cover perfectly captures the tone and texture of Zachary's tale - and you know what a special treat it is when cover art and content align in harmony.

One of my favorite paperback covers since I first came across it on one website or another, George Ziel's sensual, provocative, darkly luscious art here strikes a potential reader immediately. Who can penetrate the mystery of this woman's skyward gaze, full of awe and perhaps understanding, in thrall to some mysterious force, naked and exposed to the swamp flora crawling up her flesh as if claiming her for its own purposes? Fortunately, author Hugh Zachary is up to the task of solving this mystery; and Gwen, in Green (Fawcett Gold Medal, July 1974) is a quiet and bewitching little work that provides a bit of sexy '70s fun and fright. Ziel's cover perfectly captures the tone and texture of Zachary's tale - and you know what a special treat it is when cover art and content align in harmony.

Zachary in late Sixties

Some spoilers ahead. The back cover gives the basics. Our lovely Gwen has been married to electrical engineer George Ferrier for seven years when the story begins. After coming into family money, he's just bought a plot undeveloped land on an island on the Cape Fear River; nearby a nuclear power plant is being built (George's research shows the danger of radioactivity is, apparently, nil). So in come the developers, earth movers, bulldozers, and crewmen to clear away the swamp and brush and undergrowth and build the Ferriers' new home. Here they indulge in a full and healthy sex life (a large part of the novel which Zachary delights in) but Gwen, whose childhood was one of misfortune and neglect, still feels twinges of shame and guilt: her widowed mother was a loose woman

who wasn't careful about keeping the bedroom door closed.

A complex grew, encouraged by the teasing by Gwen's schoolmates, and so

as an adult Gwen considers herself a prude, a nut - in the parlance of

the day, frigid.

But gentle and patient he-man paramour George has coaxed Gwen into experiencing much sexual pleasure (no way this modern man's wife is gonna be frigid! All she needs is a real man's touch seems to be his motto):

And so it goes. Husband and wife now engage in playful banter (which of course includes some rape references that will bemuse today's reader) and a newfound happiness. Gwen begins painting trees and caring for lush African violets, and becomes enamored of the Venus fly-trap plants she finds at a nearby lake and begins feeding raw hamburger. But creeping into this domestic bliss are her nightmares: the mass roared down on her, huge teeth snapping at her. The mouth closed, clashing metal teeth, and she screamed once before she felt the tender flesh being punctured and rendered. Her upper body fell, being ripped from her legs and stomach and hips...

But gentle and patient he-man paramour George has coaxed Gwen into experiencing much sexual pleasure (no way this modern man's wife is gonna be frigid! All she needs is a real man's touch seems to be his motto):

She lay in total darkness, limply submitting to his touch, his obscene kiss, his fast, labored breathing. And her clitoris swelled. A tendril of something went shooting down, down, centered there. She jerked her eyes open, shocked. A stiffening in her legs, an almost imperceptible lifting of her loins... She found that certain body movements are instinctive.

And so it goes. Husband and wife now engage in playful banter (which of course includes some rape references that will bemuse today's reader) and a newfound happiness. Gwen begins painting trees and caring for lush African violets, and becomes enamored of the Venus fly-trap plants she finds at a nearby lake and begins feeding raw hamburger. But creeping into this domestic bliss are her nightmares: the mass roared down on her, huge teeth snapping at her. The mouth closed, clashing metal teeth, and she screamed once before she felt the tender flesh being punctured and rendered. Her upper body fell, being ripped from her legs and stomach and hips...

These dreams continue till one afternoon while George is at work, Gwen seduces a meter reader. Yep, you read right; the classic porn scenario. It's rather an out-of-body experience for Gwen, and she's shocked and mortified by the physical act she's shared with a stranger.

This is some serious '70s softcore! Sadly a suicide attempt is next. George and their doctor set her up with elderly psychiatrist Dr. Irving King - a Freudian by training, who had developed some rather independent ideas in thirty-five years of practice in an area of the country where psychiatry was not fully understood - and the required questioning begins, and we can begin to fathom Gwen's disordered mind. "Have you ever killed anything, Gwen?" "No. Oh, insects. Plants." "Plants?" "Isn't that silly?" And off we go! Gwen is slowly but surely identifying, in her mind, with the flora all about her on their spot of land, the Venus fly-traps, the African violets, the giant trees, the slimy green things beneath the water - all of which are being torn asunder by the developers and even her husband. Gwen feels mad, invaded, but by what? The painful dreams continue... and so do the illicit trysts. Only sex can ease the horrific sensation of dismemberment. Happy George has no idea that his wanton, sexy, endlessly hungry woman is truly not herself any longer.

And so sex and death commence to commingle. The men who drive the bulldozers come one by one to Gwen (sometimes not even one by one). They don't return to drive the bulldozers. Dr. King suspects, researches, finds, confronts. We get a crazy, nutty explanation for Gwen's "possession" that could be real or could be her own sexual, perhaps even maternal, guilt turning round on her and eating her up. Zachary hints one way, then the other, then the tale ends as the sharp reader will have predicted. It couldn't go any other way, and do I love doomy downward spirals. She continued to chop, breathing in sobbing agony. The strap to her bikini top had broken. The small scrap of material hung from her neck, flapping with her movements. Water and perspiration and blood beaded her lower legs.

I found Gwen to be a mild and relaxing read; nothing earth-shattering, but confidently written and just odd enough (and oh-so-'70s enough) to keep me reading happily. I liked the cozy, isolated forested locale; Zachary puts in

lots of detail about how rewarding working your own land is. Characters have specific natures and interior thoughts that ring true. The plentiful sex scenes were done well, Zachary knowing when to be graphic and when to leave us to fill in the blanks. Even Gwen's dalliances with teen boys were more hilariously dated than

ickily offensive (again, the anything-goes vibe of the '70s !). The

sexism that pops up in the book raises a chuckle and can be forgiven; after their first meeting, Dr. King says to Gwen, "You are much too pretty to be eaten by nightmare things," or when she tells George her bizarre dreams and he chides her, "You are one spooky broad." And yes, good death scenes that have bite, reminding me some of Michael

McDowell: a nice leisurely story carrying you along then boom, a short

sharp shock of violence.

Postscript: Some background on what surely inspired the novel. In 1973 the nonfiction book The Secret Life of Plants was first published. A bestselling and highly popular book of its day, it even became a film documentary (with a soundtrack by Stevie Wonder!). However it was speculative pseudoscience, appealing to hippies and to folks amenable to proto-New Age ideals filtering into the mainstream, swept along in the same current as astrology, crystal healing powers, and the lost continent of Mu. Secret Life's bubble-headed thesis was that plants have sentience and emotion, even telepathic powers, all girded by laughable "scientific" "experiments" like attaching polygraph electrodes to plant leaves. I know, I know! Whether he meant to satirize the theory or not, Zachary uses it as the launching pad for Gwen. In horror fiction, that sort of nonsense is a plus. Had I not worked in a used bookstore in the late 1980s and saw old copies of Secret Life, I wouldn't have been aware of it as the novel's impetus. It won't really affect your enjoyment of Gwen, but I myself dig the dated context.

She held her arms out, smiling. No question of morality. No right. No wrong. It was the way things were. Fertile, ripe, passive, she accepted him, eased his fevered haste, and bathed him in the sweet juices of her body.

1976 Coronet UK w/ art by Jim Burns

(I blacked out spoiler tagline)

This is some serious '70s softcore! Sadly a suicide attempt is next. George and their doctor set her up with elderly psychiatrist Dr. Irving King - a Freudian by training, who had developed some rather independent ideas in thirty-five years of practice in an area of the country where psychiatry was not fully understood - and the required questioning begins, and we can begin to fathom Gwen's disordered mind. "Have you ever killed anything, Gwen?" "No. Oh, insects. Plants." "Plants?" "Isn't that silly?" And off we go! Gwen is slowly but surely identifying, in her mind, with the flora all about her on their spot of land, the Venus fly-traps, the African violets, the giant trees, the slimy green things beneath the water - all of which are being torn asunder by the developers and even her husband. Gwen feels mad, invaded, but by what? The painful dreams continue... and so do the illicit trysts. Only sex can ease the horrific sensation of dismemberment. Happy George has no idea that his wanton, sexy, endlessly hungry woman is truly not herself any longer.

And so sex and death commence to commingle. The men who drive the bulldozers come one by one to Gwen (sometimes not even one by one). They don't return to drive the bulldozers. Dr. King suspects, researches, finds, confronts. We get a crazy, nutty explanation for Gwen's "possession" that could be real or could be her own sexual, perhaps even maternal, guilt turning round on her and eating her up. Zachary hints one way, then the other, then the tale ends as the sharp reader will have predicted. It couldn't go any other way, and do I love doomy downward spirals. She continued to chop, breathing in sobbing agony. The strap to her bikini top had broken. The small scrap of material hung from her neck, flapping with her movements. Water and perspiration and blood beaded her lower legs.

Zachary wrote under pseudonym Zach Hughes. Dig Tide 1975!

Gwen, in Green, is a satisfying work of smart, fun, pulp horror that could only have been written in the early 1970s. Which is one of my highest compliments! Find a copy, admire its magnificent cover, and read while sipping a gin & tonic under the summer sun near a crystal-clear lake beneath towering, creeping greenery. Shouldn't take you more than an afternoon or two to read it, but you just might feel differently about that vegetation when you're done.

Postscript: Some background on what surely inspired the novel. In 1973 the nonfiction book The Secret Life of Plants was first published. A bestselling and highly popular book of its day, it even became a film documentary (with a soundtrack by Stevie Wonder!). However it was speculative pseudoscience, appealing to hippies and to folks amenable to proto-New Age ideals filtering into the mainstream, swept along in the same current as astrology, crystal healing powers, and the lost continent of Mu. Secret Life's bubble-headed thesis was that plants have sentience and emotion, even telepathic powers, all girded by laughable "scientific" "experiments" like attaching polygraph electrodes to plant leaves. I know, I know! Whether he meant to satirize the theory or not, Zachary uses it as the launching pad for Gwen. In horror fiction, that sort of nonsense is a plus. Had I not worked in a used bookstore in the late 1980s and saw old copies of Secret Life, I wouldn't have been aware of it as the novel's impetus. It won't really affect your enjoyment of Gwen, but I myself dig the dated context.

Friday, December 20, 2013

Friday I'm in Love 3: George Ziel Gothic Cover Art

The late George Ziel was a paperback cover artist extraordinaire. I can't get enough of his style, and his work for the Gothic romance craze of the late 1960s and early '70s has become nearly iconic. Here are some dark, lovely Gothic ladies to enjoy, and for more about Ziel the man and the artist, be sure to visit Lynn Munroe Books, Unobtanium 13, and The Midnight Room.

Sunday, May 5, 2013

And the Night When the Wolves Cry Out

Here's some moody werewolf cover art for you, thanks to good old George Ziel. I've been remiss in my posting, but I finished a '90s horror antho last week and have slooowly been working up my review. Till then...

Friday, August 10, 2012

Monday, March 5, 2012

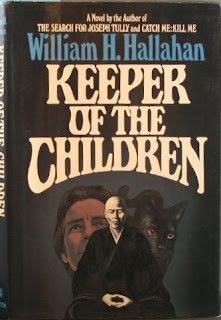

Keeper of the Children by William H. Hallahan (1978): On the Highest Trails Above

At first glance - and at second and third - this George Ziel cover for Keeper of the Children, the fifth thriller from William H. Hallahan, seems silly and absurd and inconceivable. Surely it represents nothing that could possibly appear in a novel for adults, could it? Well... it certainly does. It is an exact representation of a scene from late in the book. And Hallahan improbably makes it work. He's got folks astral-projecting - not too '70s now! - into all manner of objects animate and not, like children's toys and feral cats and in one terrifying scene, a scarecrow. You can read it all on the back cover here, if you want:

At first glance - and at second and third - this George Ziel cover for Keeper of the Children, the fifth thriller from William H. Hallahan, seems silly and absurd and inconceivable. Surely it represents nothing that could possibly appear in a novel for adults, could it? Well... it certainly does. It is an exact representation of a scene from late in the book. And Hallahan improbably makes it work. He's got folks astral-projecting - not too '70s now! - into all manner of objects animate and not, like children's toys and feral cats and in one terrifying scene, a scarecrow. You can read it all on the back cover here, if you want: Fourteen-year-old Renni Benson and her bestie Pammy Garman have "willingly" joined a panhandling Philadelphia cult led by a Vietnamese refugee named Kheim, a Buddhist monk. Lots of other young teens have done the same, and their heartbroken parents see them on the well-evoked dirty Philly streets begging for coins in worn-out clothes. Several of these parents form a committee to get their kids back after learning what a danger Kheim is, but apparently back in the day cops weren't too weirded out by such occurrences. Indeed, Pammy's mother and father don't seem too concerned, even relieved, since now they can indulge in more gin on the rocks and spousal abuse, respectively. Even Eddie Benson, the hero and Renni's father, doesn't seem nearly as worried at first as you can imagine a parent would be today. It's a little jarring to a modern reader, even one without children.

Fourteen-year-old Renni Benson and her bestie Pammy Garman have "willingly" joined a panhandling Philadelphia cult led by a Vietnamese refugee named Kheim, a Buddhist monk. Lots of other young teens have done the same, and their heartbroken parents see them on the well-evoked dirty Philly streets begging for coins in worn-out clothes. Several of these parents form a committee to get their kids back after learning what a danger Kheim is, but apparently back in the day cops weren't too weirded out by such occurrences. Indeed, Pammy's mother and father don't seem too concerned, even relieved, since now they can indulge in more gin on the rocks and spousal abuse, respectively. Even Eddie Benson, the hero and Renni's father, doesn't seem nearly as worried at first as you can imagine a parent would be today. It's a little jarring to a modern reader, even one without children.I think this was common coin in the early to mid 1970s: after the murderous Manson girls and groupies you had the Moonies and the Hare Krishnas, and at least in big cities, runaway kids joining these cults, too young and naive and perhaps even strung-out to realize they were being used and exploited by con men operating under the guise of New Age-y enlightenment. That must explain the parents' early reactions to their missing kids. Anyway, when Benson learns that Kheim is a master of astral projection, he visits a yogi named Nullatumbi, who puts Benson to some serious training of his sloppy Western mind, introducing him to psychokinesis and out-of-body experiences and all that kinda stuff so Benson can do astral battle with Kheim. Not too '70s now indeed.

Hallahan, who wrote one helluva good chilly occult suspense novel called The Search for Joseph Tully, is a careful and serious writer, making the absurd plausible and wringing satisfying suspense out of it. When Benson finally masters astral projection, we feel the spooky endless emptiness of outer space itself:

...he saw the multitude of stars that surrounded him. He seemed to be crossing an entire galaxy. Now the pain came. It focused at one point - a paralyzing, unforgiving point of pain. He'd stopped in the midst of the stars, a throbbing point of pain in the universe attached to a thin silver cord that meandered away in the dark... If the cord had broken, he was dead, never to reenter his body. And his presence would wander in space forever.

1980 Sphere UK paperback

1980 Sphere UK paperback

1980 Sphere UK paperback

1980 Sphere UK paperbackThat is what Benson is risking when he goes to rescue his daughter. Heavy. There's also an excellent bit of literal cat-and-mouse (well, rat) violence, a sequence that I suppose made sense in those Watership Down days. But I feel like Keeper could have been a longer novel, as it's not even 200 pages in this Avon paperback. I could've used more background on the cult, on Kheim, on what the children truly experienced as they were "kept." It feels a bit thin and a tad underdone in spots; even Benson seems somewhat of a cipher. I think Keeper of the Children will provide enjoyment for folks who like this kind '70s occult fiction, but for me, I much preferred The Search for Joseph Tully.

Tuesday, February 21, 2012

R. Chetwynd-Hayes: The George Ziel Paperback Covers

The little-known George Ziel is quickly becoming one of my very favorite paperback cover artists. Here you see the wonderfully macabre illustrations he did for the 1970s Pyramid Books editions of R. Chetwynd-Hayes's short story collections (which I haven't read). Zeil paints sultry, sexy, deadly, slightly maddened women, malevolently blank-eyed skulls, drifting tendrils of mist and clouds of living darkness, and mysterious men who blur the line between saviors and psychos like someone with a direct line to their roiling subconscious (of course he was a Holocaust survivor). That gangrenous gray-green hue should be de rigueur for all horror fiction paperbacks!

The little-known George Ziel is quickly becoming one of my very favorite paperback cover artists. Here you see the wonderfully macabre illustrations he did for the 1970s Pyramid Books editions of R. Chetwynd-Hayes's short story collections (which I haven't read). Zeil paints sultry, sexy, deadly, slightly maddened women, malevolently blank-eyed skulls, drifting tendrils of mist and clouds of living darkness, and mysterious men who blur the line between saviors and psychos like someone with a direct line to their roiling subconscious (of course he was a Holocaust survivor). That gangrenous gray-green hue should be de rigueur for all horror fiction paperbacks! See more of Ziel's amazing, alluring work for horror, crime, mystery, Gothic and other vintage genre paperbacks here. And yes, you're welcome.

See more of Ziel's amazing, alluring work for horror, crime, mystery, Gothic and other vintage genre paperbacks here. And yes, you're welcome.

Wednesday, December 28, 2011

"...the most poetical topic in the world."

"The death, then, of a beautiful woman is, unquestionably, the most poetical topic in the world."

E.A. Poe.

"The Philosophy of Composition" (1846)

Lingard by Colin Wilson (1970)

1980 Pocket Books cover art by George Ziel

"The Philosophy of Composition" (1846)

Lingard by Colin Wilson (1970)

1980 Pocket Books cover art by George Ziel

Labels:

'70s,

'80s,

colin wilson,

george ziel,

novel,

pocket books,

poe,

unread

Saturday, October 1, 2011

Frights, Night Chills, and Beyond Midnight: The '70s Anthologies of Kirby McCauley

Loving these paperback covers from the horror anthologies that Kirby McCauley edited in the 1970s. McCauley wasn't a horror writer himself; he's a literary agent, and one of his early clients was Stephen King himself (among plenty others). The art on these books is a terrific example of the creepy and the surreal from that wonderful era.

Loving these paperback covers from the horror anthologies that Kirby McCauley edited in the 1970s. McCauley wasn't a horror writer himself; he's a literary agent, and one of his early clients was Stephen King himself (among plenty others). The art on these books is a terrific example of the creepy and the surreal from that wonderful era. Frights (Warner Books, 1977), with cover art from George Ziel, contains stories by Bloch, Etchison, Campbell, and Robert Aickman (gotta get around to covering Aickman here!), as well as SF&F authors - for whom McCauley worked - Joe Haldeman, David Drake, and Poul Anderson. Love the noseless woman; horrifying. The little hunchbacked figure makes me think of du Maurier's "Don't Look Now." Cool to see the "No more vampires, werewolves, or crumbling castles" too - now it's time for horror to get modern. This UK edition of part of Frights looks more like a vintage 1980s Iron Maiden album cover!

Frights (Warner Books, 1977), with cover art from George Ziel, contains stories by Bloch, Etchison, Campbell, and Robert Aickman (gotta get around to covering Aickman here!), as well as SF&F authors - for whom McCauley worked - Joe Haldeman, David Drake, and Poul Anderson. Love the noseless woman; horrifying. The little hunchbacked figure makes me think of du Maurier's "Don't Look Now." Cool to see the "No more vampires, werewolves, or crumbling castles" too - now it's time for horror to get modern. This UK edition of part of Frights looks more like a vintage 1980s Iron Maiden album cover!

Night Chills (Avon, 1975) Could that be the one and only Abdul Alhazred gracing this cover?! Might be; there are stories from Lovecraft and Derleth, plus you got Manley Wade Wellman, Joseph Payne Brennan, and Carl Jacobi. Night Chills even features the first paperback appearance of Karl Edward Wagner's rural classic "Sticks." Cover artist is unknown; he probably disappeared not long after daring to depict the unholy visage of that mad, mad, mad Arab. Tough luck, guy!

Night Chills (Avon, 1975) Could that be the one and only Abdul Alhazred gracing this cover?! Might be; there are stories from Lovecraft and Derleth, plus you got Manley Wade Wellman, Joseph Payne Brennan, and Carl Jacobi. Night Chills even features the first paperback appearance of Karl Edward Wagner's rural classic "Sticks." Cover artist is unknown; he probably disappeared not long after daring to depict the unholy visage of that mad, mad, mad Arab. Tough luck, guy! Beyond Midnight (Berkley Medallion, 1976) More HPL, and also classic writers like Ambrose Bierce and M.R. James, as well as Weird Tales brethren like Bradbury, Robert E. Howard, and A. Merritt. The "Twilight Zone"-style cover art's by Vincent DiFate.

Beyond Midnight (Berkley Medallion, 1976) More HPL, and also classic writers like Ambrose Bierce and M.R. James, as well as Weird Tales brethren like Bradbury, Robert E. Howard, and A. Merritt. The "Twilight Zone"-style cover art's by Vincent DiFate.Of course in 1980, McCauley would edit Dark Forces, the seminal and genre-busting anthology that inspired new horror writers for the new decade...

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)