Now, independent publisher Fathom Press, taking a cue from Valancourt Books' Paperbacks from Hell line, is going after white whales like this one. And this one was captured! Fathom was able to secure reprint rights from Canadian author Barry Hammond, who even contributed an explanatory and insightful afterword about the origins of his sole horror novel. (While writing, Hammond says he was playing difficult-listening albums by Lou Reed and Nico to capture the right vibe he was imagining, truly fitting.)In Cold Front, Hammond doesn't even pretend to try to get you to identify with his three male leads. These guys are dumb, grimy, pig-ignorant losers who speak like it; no Tarantino pulp-crime pop-culture witticisms, no self-referential jokes, no self-aware callbacks. You're in the company of some real ugly drunken dum-dums, and it ain't fun. Hammond has a way of setting up a scenario that's pure no-way-out hopelessness. The almost-sole locale of the disgusting cabin in the snowy wilderness also functions as a kind of freezing existential locus, stripped of all extraneousness, few provisions, howling storm outside, confronting sex and terror inside this desolate dwelling that seems to exist in some netherworld, a purgatory hungry for lives to send on to Hell.

Sure, there's gonna be things to be grossed out by in a trashy Eighties horror paperback novel like this: the crude jokey racial comments, the "childlike sexuality" of the bizarrely pale white girl the men find hiding in the cabin's basement, the threat of rape and worse. Silent and mysterious, yet able to kick ass and defend herself, the young woman both attracts and repels each trapped man. The blurb on the back cover gets it right: it's not the girl they need to be afraid of...

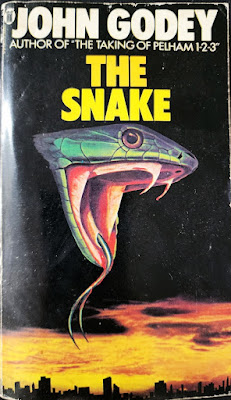

As I read, I got notes of Jim Thompson crime novels, and of Laymon/Ketchum in the simplicity of setup and prose style, grue and bloodshed. Our monster, hinted at throughout—and ably represented in the Signet cover art, by the great Tom Hallman—is underplayed till the end, which is quite the frigid whirlwind of death and mayhem. While I wouldn't say I "enjoyed" Cold Front, I absolutely appreciated its commitment to single-minded unease, disgust, and fatalistic despair. And thanks to Fathom Press, you can now "enjoy" it as I did as well!

With the sun full on them, they were the very centre of the horror before they realized what it was... Then the pieces of it hanging from the trees seared their eyes. They could see the silhouettes. Not understand them, but know who it was from the shreds of wool still attached to the raw, frozen meat. Not understand how such a thing was possible. Logic of human geometry had been thrown aside. That the human body could undergo such stretching, ravaging, seemed impossible. The image indelibly inked across their minds even when they closed their eyes. Hard to believe that such obscenity could exist in sunlight.