Friday, July 24, 2015

Thursday, July 23, 2015

Friday, July 17, 2015

Wednesday, July 15, 2015

Borderlands 2, ed. by Thomas F. Monteleone (1991): It's a Long Way Back from Hell

"The stories which follow don't have to be read on a dark night, with glowing embers banked in the fireplace, and a dark wind howling across the moors. You can read these tales under the clear light of day and pure reason... None of the tired old symbols which have defined the genre for far too long will be found here."

Editor Thomas F. Monteleone, introduction

How could any editor put together such a trailblazing anthology as 1990's Borderlands and not desire to follow it up with another volume? Again, Monteleone has gathered together stories by writers both (in)famous and not, stories that don't fit comfortably under the generic rubric of "horror," or any other either. Borderlands 2 (Avon Books, Dec 1991) treads a dangerous line: in its efforts to present horror/dark fantasy/suspense/science fiction stories that fit no mold it risks pretension, ambition outstripping execution (Prime Evil, anyone?); stay too close to identifiable territories and it is simply another paperback horror anthology cluttering up the shelves. The original Borderlands is one of my top favorites ever precisely because it tight-roped that line perfectly. Can Monteleone (pic below) and cohorts do it again?

For the most part, yes.

Disturbing is a word I'd use to describe the fictions herein; disturbing, unsettling, poignant, grotesque. Horror is normalized; lived with, understood as a fact of life, and isn't really scary anymore. Here there are moments struck in which I felt my flesh turn inside out, my shoulders shivering with revulsion, while my brain was engaged by a story's central idea, or an image or an implication. A writer who can do that to me—delight my mind while revolting my body—will have my undying devotion. And the story here that completely knocked me out, kept me glued to the page with a well-told tale and imagery of primal horror, was "Breeding Ground," by a man named Francis J. Matozzo.

I doubt you know that name. He had a story in the original Borderlands, "On the Nightmare Express," which was kinda cool. In this one he details three seemingly disparate events: a man undergoing surgery for excruciating craniofacial pain, an amateur archaeological expedition, a woman estranged from her husband. It's how Matozzo fractures the story and then pieces it back together, building suspense, that really won me over. Also, I dig evolutionary biology and that figures in here too, both literally and as analogy. Skin-crawlingly disgusting and sadly effective, "Breeding Ground" succeeds at all levels.

Another strong work is Ian McDowell's "Saturn," which is not a reference to the planet but to the Roman god who, well, devours his children. It is filled with grim wit and ends on one of the darkest notes in the anthology. Yes, I killed Michael. And buried his head, hands, feet, and bones in the geranium bed, after eating the rest. I can't even honestly say I regret it, although I'm sorry you have to find out.

One of the longest stories is "Churches of Desire" by the late Philip Nutman (pictured above at an archaic contraption known as, I think, "typewriter"). Clearly inspired by Clive Barker, a film journalist wanders through Rome, marveling at its filthy wonders and trying to pick up young men for anonymous trysts when he's not futilely attempting to interview an aging exploitation filmmaker. The "church of desire" is a porno theater, of course, and our protagonist eventually succumbs to its offerings, a depraved celluloid vision that would make Pasolini blush. While it may be too beholden to Barker, especially in its final paragraphs, "Churches of Desire" satisfies. The Church would welcome fresh converts that night and there would be new films to watch, new stories to tell, his own among them. In the name of the Father and the Son the congregation would sing silent praises to the Gods of Flesh and Fluids.

Sexual politics are a prominent feature in Borderlands 2, as the culture at large was beginning to deal with them in the early 1990s. The lead-off story, from F. Paul Wilson (of whom I am no fan) is "Foet," a so-so satire of high fashion and the absurd lengths to which people go in order to be stylish. You can probably guess the gimmick from the title. As with his notorious "Buckets," I found the approach over-done and the effect reactionary, which mitigates the shock factor. Better: "Androgyny," by Brian Hodge (pictured above), a sympathetic and relevant fantasy about a marginalized people, while Joe Lansdale's "Love Doll: A Fable" is an unsympathetic portrayal of someone who enjoys marginalizing those less fortunate, or simply those not born straight white blue-collar male.

"Dead Issue," from Slob author Rex Miller, doesn't have enough moral weight to justify its graphic sexual violence. Pass. "Sarah, Unbound," from which the Avon paperback chose its cover image, is Kim Antieau's solid contribution about a woman exorcising her real-life demons (She hated him so much. She had loved him. Why had he done it?) by counseling an imaginative yet abused child.

Borderlands Press hardcover, Oct 1991, Rick Lieder cover art

David B. Silva, the late editor of Horror Show magazine, returns to Borderlands with the final story, "Slipping." Like his award-winning "The Calling," "Slipping" is about real-life fears: in the former it was cancer, here it is aging. A hard-working ad man finds moments of his life disappearing from his memory, hours, then days. One moment he's at work, the next he's on the phone with his ex-wife, then he's having lunch with a colleague, with no conscious memory of how he got to any of those points. Silva makes the reader feel the terrible incomprehension of being aware of that incomprehension... but being powerless to stop it. Excellent. The physical distress of aging also appears in Lois Tilton's "The Chrysalis"; a character's dawning horror at its climax was a favorite moment of mine.

Children are horrible, aren't they? A classic horror trope. Facing the sins of our past, our guilt unassuaged by time or deed, is central to Paul F. Olson's "Down the Valley Wild," a sensitive, painful rumination on a childhood 40 years gone. It also contains some well-rendered moments of shock; overall it was a highlight of the book for me. "Taking Care of Michael" is only a page and a half long but J.L. Comeau's prose cuts deep and ugly, presenting madness under the guise of innocence.

White Wolf reprint, Oct 1994, Dave McKean cover art

All that said, Borderlands 2 also includes a handful of stories I found middling, so this volume doesn't quite reach the heights of its predecessor. These stories—"The Potato" by Bentley Little, "For Their Wives Are Mute" by Wayne Allen Sallee, "Apathetic Flesh" by Darren O. Godfrey, "Stigmata" by Gary Raisor—have their peculiarities, their moments of squick and dread, sure, but lack a certain edge to really sledgehammer the reader. Of course mileage may vary; other than Rex Miller's story none of them outright suck, and I think most readers will find much of Borderlands 2 to be an excellent usage of their time. Monteleone wisely continued the series for several more volumes, most of which I read as they were published through the mid-'90s—I clearly recall buying this one upon publication, eager and excited to delve into "steaming, stygian pools of unthinkable depravity"—and I hope to own them all again one day soon. Rest assured that all my future trips to "uncharted realms of bloodcurdling horror" will be documented and presented here, trespassing be damned.

Thursday, July 9, 2015

Today in Horror Birthdays

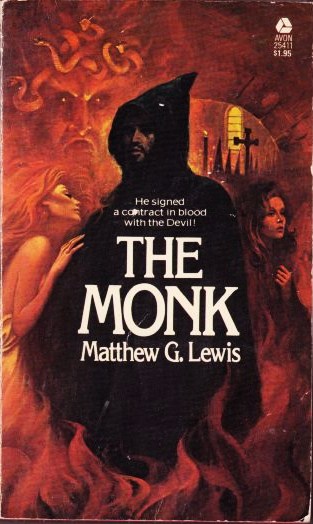

Matthew Gregory Lewis (1775 - 1818), who wrote the lurid Gothic novel The Monk, published in 1796. Here you see the 1975 Avon paperback

Ann Radcliffe (1764-1823), author of the first true Gothic romance The Mysteries of Udolpho (1794). Date unknown for this Penguin paperback.

Dean R. Koontz (1945), the man behind bestsellers too numerous to count. I liked Watchers (1987) and Lightning (1988) back in high school. These are the first-edition Berkley paperbacks.

The ever-enigmatic Thomas Ligotti (1953), whose exquisitely weird short fiction was first collected in Song of a Dead Dreamer back in 1985 by Silver Scarab Press.

And Philip Nutman (1963-2013), journalist and author. His "Full Throttle" was a terrific entry in 1990's Splatterpunks.

Ann Radcliffe (1764-1823), author of the first true Gothic romance The Mysteries of Udolpho (1794). Date unknown for this Penguin paperback.

The ever-enigmatic Thomas Ligotti (1953), whose exquisitely weird short fiction was first collected in Song of a Dead Dreamer back in 1985 by Silver Scarab Press.

And Philip Nutman (1963-2013), journalist and author. His "Full Throttle" was a terrific entry in 1990's Splatterpunks.

Thursday, July 2, 2015

They Thirst by Robert R. McCammon (1981): When the Night Comes Down

A sprawling vampire epic set in the glittering midnight environs of the City of Angels, Hollywood USA, They Thirst (Avon Books, May 1981) was the fourth paperback original by Robert R. McCammon. Eventually McCammon would disown those first four novels, pulling them from print, saying they didn't represent him at his best. Fair enough, I guess, I don't know many authors that would do that kind of thing. But when I look at reviews of They Thirst on Goodreads and Amazon I see that most readers don't feel the way McCammon does: they fucking love this novel. Love. It. Like "greatest vampire novel" ever love it.

So I feel a bit bad when my reaction to the book is indifference, even impatience, same as to the other McCammon I've read. Lots of telling, telling, telling—over 500 pages of telling—and no showing. On a line-to-line basis McCammon's not a bad writer, he's just bland and pedestrian, with little snap, wit, or insight in his prose. Characters, while plentiful, are stock folks, and the story too thinly reads like 'Salem's Lot transferred to the opposite coast. His main weakness is telling the readers what they already know, and this chokes the story up, slows it to a crawl. Too many characters doubt for too long, or wonder aloud at their life-threatening predicament, or argue a moot point. I skimmed all that junk, looking for nuggets of story, of narrative, of bloodshed, to clear out all that baggage. There are moments, to be sure, that work, but far too few. Like too many '80s horror novels, They Thirst feels overstuffed for no discernible reason.

It's not a terrible set-up, but I tire of these broad scenarios with dozens of characters and locales. Fortunately things begin to tighten up once Prince Vulkan—how do people not know a guy with a name like that is a vampire?—appears on the scene. As he explains his nefarious plans to his two fave-rave henchmen his mind wanders back through his past, to his becoming undead 500 years ago. Here McCammon does some solid writing, even though he's doing nothing new really, but Vulkan's drive to become king vampire is well-evoked, and the fact that Vulkan was made nosferatu at a petulant 17 years of age, is unique. Were that there were even more of these kinds of tiny inventive touches! The final third or maybe quarter of They Thirst is made up of four vampire hunters tracking the creatures to their ultimate lair high in the Hollywood Hills. This is Castle Kronsteen, a massive edifice built on a cliff by '40s monster-movie star Orlon Kronsteen, who was found murdered in it, decapitated no less, 15 years prior to the events of the novel. Yes: Kronsteen's function is the same as the Marsten's House in 'Salem's Lot.

Indeed, King's shadow looms large, too large. They Thirst reads like a combo of The Stand and 'Salem's Lot, a vampire apocalypse loosed upon the world. Young Tommy is basically Mark Petrie, a loner kid with a penchant for Lovecraft and horror movies; rising TV comedian Wes Richter is Larry Underwood; Padre Silvera is Father Callahan (although he's not a drunken coward); homicide detective Andy Palatazin is plagued by his own childhood demons (which comprises the novel's prologue) like Ben Mears. There's even a plucky tabloid reporter as in The Dead Zone. I kinda liked "Ratty," a burned-out grime-encrusted leftover hippy living in the LA sewer system, who helps Tommy and Palatazin navigate the underground tunnels but first he tries to sell them hallucinogenics. Their subterranean journey reminded me of the Lincoln Tunnel chapters in The Stand—surely one of King's greatest sequences of terror—but is nowhere near its heights in execution. The novel's climax, a literal earthshaker, is mighty but reeks of deus ex machina.

They Thirst is not a bad horror novel, it's not insulting like, say, The Keep or The Cellar, and I guess I can see how so many readers value it; but to me it is an unnecessary horror novel. I ask myself: had I first read this book when I was a teenager, would I have enjoyed it? I'm not sure I would have: too much like King, not sexy at all, nothing new is done with vampire lore, and its violence is standard (although more than once I sensed an interesting John Carpenter movie going on). Probably in 1981 the book made more of an impact; Avon Books certainly went all out in promoting it so could it be I'm being too hard on it? Maybe I am. Will I read one of McCammon's later books, one that he's not embarrassed by? Maybe I will.

So I feel a bit bad when my reaction to the book is indifference, even impatience, same as to the other McCammon I've read. Lots of telling, telling, telling—over 500 pages of telling—and no showing. On a line-to-line basis McCammon's not a bad writer, he's just bland and pedestrian, with little snap, wit, or insight in his prose. Characters, while plentiful, are stock folks, and the story too thinly reads like 'Salem's Lot transferred to the opposite coast. His main weakness is telling the readers what they already know, and this chokes the story up, slows it to a crawl. Too many characters doubt for too long, or wonder aloud at their life-threatening predicament, or argue a moot point. I skimmed all that junk, looking for nuggets of story, of narrative, of bloodshed, to clear out all that baggage. There are moments, to be sure, that work, but far too few. Like too many '80s horror novels, They Thirst feels overstuffed for no discernible reason.

Pocket Books reprint, Oct 1988, Rowena Morrill cover art

It's not a terrible set-up, but I tire of these broad scenarios with dozens of characters and locales. Fortunately things begin to tighten up once Prince Vulkan—how do people not know a guy with a name like that is a vampire?—appears on the scene. As he explains his nefarious plans to his two fave-rave henchmen his mind wanders back through his past, to his becoming undead 500 years ago. Here McCammon does some solid writing, even though he's doing nothing new really, but Vulkan's drive to become king vampire is well-evoked, and the fact that Vulkan was made nosferatu at a petulant 17 years of age, is unique. Were that there were even more of these kinds of tiny inventive touches! The final third or maybe quarter of They Thirst is made up of four vampire hunters tracking the creatures to their ultimate lair high in the Hollywood Hills. This is Castle Kronsteen, a massive edifice built on a cliff by '40s monster-movie star Orlon Kronsteen, who was found murdered in it, decapitated no less, 15 years prior to the events of the novel. Yes: Kronsteen's function is the same as the Marsten's House in 'Salem's Lot.

Sphere Books UK, 1981

Indeed, King's shadow looms large, too large. They Thirst reads like a combo of The Stand and 'Salem's Lot, a vampire apocalypse loosed upon the world. Young Tommy is basically Mark Petrie, a loner kid with a penchant for Lovecraft and horror movies; rising TV comedian Wes Richter is Larry Underwood; Padre Silvera is Father Callahan (although he's not a drunken coward); homicide detective Andy Palatazin is plagued by his own childhood demons (which comprises the novel's prologue) like Ben Mears. There's even a plucky tabloid reporter as in The Dead Zone. I kinda liked "Ratty," a burned-out grime-encrusted leftover hippy living in the LA sewer system, who helps Tommy and Palatazin navigate the underground tunnels but first he tries to sell them hallucinogenics. Their subterranean journey reminded me of the Lincoln Tunnel chapters in The Stand—surely one of King's greatest sequences of terror—but is nowhere near its heights in execution. The novel's climax, a literal earthshaker, is mighty but reeks of deus ex machina.

Sphere Books UK, 1990

They Thirst is not a bad horror novel, it's not insulting like, say, The Keep or The Cellar, and I guess I can see how so many readers value it; but to me it is an unnecessary horror novel. I ask myself: had I first read this book when I was a teenager, would I have enjoyed it? I'm not sure I would have: too much like King, not sexy at all, nothing new is done with vampire lore, and its violence is standard (although more than once I sensed an interesting John Carpenter movie going on). Probably in 1981 the book made more of an impact; Avon Books certainly went all out in promoting it so could it be I'm being too hard on it? Maybe I am. Will I read one of McCammon's later books, one that he's not embarrassed by? Maybe I will.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)