I think that 2014 was the best year yet for Too Much Horror Fiction: the blog reached a million views, I wrote two series on horror fiction at Tor.com, and read some great books for the first time. In no particular order I present my fave horror reads of the past year.

The Face That Must Die by Ramsey Campbell. An all-too-convincing portrait of the murderer's mind. The intro essay, Campbell's account of his mother's mental illness, is essential reading.

The Nest by Gregory A. Douglas. Repulsive pulp chiller that delivers. Too bad more Zebra horror paperbacks weren't this outrageous.

Feral by Berton Roeche. Understated thriller about cats on the attack. Rouche as an unassuming, quiet and literate prose style that heightens the tale's believability (some boneheaded Amazon reviewers think this

means the guy can't write).

Burning by Jane Chambers. A haunting historical love story about a forbidden love. I know that sounds cheesy but really, this is a sensitive and thoughtful novel. Terrific cover art as well, although it probably made some folks dismiss it.

Gwen, in Green by Hugh Zachary. Erotic ecohorror with that full '70s flavor. Also one of my all-time fave covers.

Hell Hound by Ken Greenhall. A forgotten, overlooked masterpiece of the sociopathic mind of a dog. Yes, a dog. Hope someone publishes a reprint.

A Nest of Nightmares by Lisa Tuttle. A powerful collection of stories that highlight horror at home. Tuttle's '80s short horror fiction should not be missed.

The Cormorant by Stephen Gregory. A gloomy, doomy, almost poetic tale about a man, his family, and his bird. Unique, startling, powerful.

Big life change too! In early June I moved to

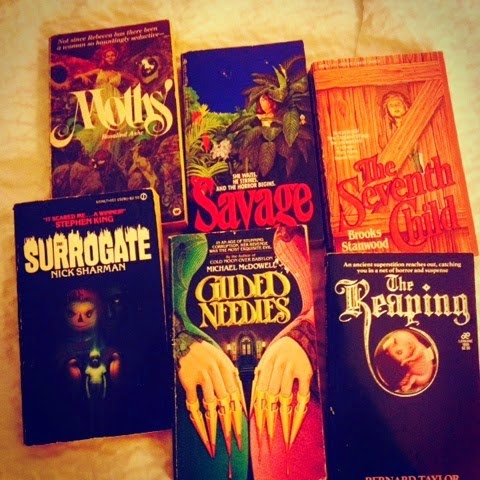

Portland, OR. Driving across the country, I visited used bookstores and added dozens of vintage paperback titles to my

shelves:

And February will be the fifth anniversary of Too Much Horror Fiction! So here's to a great 2015--who knows what horrors lie in wait...

Sunday, December 28, 2014

Wednesday, December 24, 2014

Fritz Leiber Born Today, 1910

After his wife sent a letter to Lovecraft himself in 1936, Chicago-born Fritz Leiber found an inspiring and encouraging correspondent in the Gentleman from Providence. Of course HPL died only a year later but Leiber was just beginning his long career as a master of dark fantasy. Raised by parents who were Shakespearean actors, Leiber dabbled in acting in his early life. But it was for his writing that he became most famous, perfecting the sword-and-sorcery genre with his characters Fafhrd and the Gray Mouser and producing one of my own favorite horror novels, Our Lady of Darkness (1977). He even appeared in the 1970 cult movie Equinox, in scenes which clearly prefigured the Lovecraftian "book of the dead" aspects of the original Evil Dead movies. Below you can see my small collection of Leiber's more horror-related paperbacks. Leiber died in 1992.

Wednesday, December 17, 2014

The Face That Must Die by Ramsey Campbell (1979): I'm Determined and I'd Rather See You Dead

Campbell in 1980

Face is the story of the aptly-named Horridge, a nobody kind of fellow in a precisely-drawn Liverpool, whose growing paranoia is exacerbated by his obsession/revulsion with an overweight, effeminate older man who lives in his Liverpool neighborhood. After reading in the papers about a "man whose body was found in a Liverpool flat was a male prostitute" and studying the accompanying suspect police sketch, Horridge comes to realize "he had seen the killer three times now, in as many days. That was no coincidence. But what was he meant to do?" His conviction that random events are a secret code to him alone is unshakeable.

Horridge finds out the man's name is Roy Craig by searching through library records (and mildly creeping out library clerk Cathy Gardner, who with her long-haired boyfriend Peter actually lives in the same building as Craig), Horridge begins systematically stalking and harassing the man. Craig's homosexuality—Horridge is correct in his presumption—offends him to his core: "If he was a homosexual he was perverted enough for anything." Which of course means he will continue to kill, and must be stopped by any means necessary--actually he can be stopped by any means necessary, because Horridge is doing away with degenerates and doing society a favor.

Campbell does a solid job of making the reader feel uneasy. Everywhere, things seem off: conversations are snippy, irritated, impatient; graffiti stains walkways and alleys (Horridge keeps seeing the word "killer"); the wheezing buses are crowded and smoke-filled; twilight is always seeping into Horridge's apartment; his limp is painful and insistent; library customers are resentful, grumbling at the clerks wielding petty powers (in a scene Campbell admits is autobiographical); fog prevents everyone from seeing clearly. Liverpool is as much a character as Horridge or Cathy or Peter, and at times even seems conspire against Horridge; he sees the tower blocks, rundown flats, loud pubs, grimy gutters, grey skies, and bare concrete as one big institution, a prison ready for its cowed inmates. Everywhere the banal, the mundane, threaten to swallow the sane and insane alike; the suffocation is palpable.

Sometimes he thought the planners had faked those paths, to teach people to obey without questioning... the tunnel was treacherous with mud and litter; the walls were untidy webs of graffiti. All the overhead lights had been ripped out. He stumbled through, holding breath; the place smelled like an open sewer... A dread which he'd tried to suppress was creeping into his thoughts—that sometime, perhaps in fog, he would come home and be unable to distinguish his own flat.

Immersed in Horridge's psyche, the reader is also both fascinated and revolted by his thought processes as they cycle through mania and grandiosity, memories of a painful childhood, and his ever-present desire to clean up the filth (moral and literal) he sees growing everywhere around him. Every tiny detail, every sliver of dialogue, every simile, drips with an uneasy threat of everything about to fall apart, as if reality itself were trembling on the precipice of chaos. Campbell allows us a few views outside of Horridge's, but overall we feel as he does: threatened, maligned, powerless. Then he lashes out in anonymous—and unwittingly ironic—calls to Craig: "Just remember I'm never far away. You'd be surprised how close I am to you."

1st UK paperback, Star Books Dec 1979

There is one scene I must point out. Horridge goes to the cinema to see a film, but the only title that resonates is the one that contains the word "horror" ("Horror films took you out of yourself—they weren't too close to the truth"). Check it out:

Yes: Horridge inadvertently attends a screening of The Rocky Horror Picture Show! One of the funniest and most telling—and most deserved—moments I've ever read in a horror novel (AFAIC all homophobes should have Tim Curry's Dr. Furter shoved in their faces and, yes, down their throats).Was it supposed to be a musical? He'd been lured in under false pretenses. It began with a wedding, everyone breaking into song and dance. Then an engaged couple's car broke down: thunder, lightning, lashing rain, glimpses of an old dark house. Perhaps, after all—They were ushered to meet the mad scientist. Horridge gasped, appalled. The scientist's limp waved like snakes, his face moved blatantly. He was a homosexual.This was a horror film, all right--far too horrible, and in the wrong way.

Scream/Press hardcover, Oct 1983, art by J.K. Potter

Campbell keeps the story moving quickly as Horridge's fears grow and grow. He's a bit of a walking textbook of serial killer tics and tactics, but it's not just serial killers who display these attributes. His hatred of homosexuality (his hatred of any sexuality: at one point late in the novel, Cathy is running after him, trips and falls, and Horridge hopes the breasts she flaunts have burst); his belief that society is degrading more and more; his hatred of foreigners and anyone different, gay or not; the shades of his disappointed parents hovering about him—is this an indictment of Thatcher-era England? All I know about English culture I learned from '70s punk rock, but this sounds about right. Campbell is also wise to draw a parallel between Peter and Horridge, who are both aware of how out of step they are with modern society and the paranoid fantasies this engenders in them.

Futura UK reprint, 1990

Readers who enjoy the experience of being thrust into the killer's mind will enjoy Face; no, it's no American Psycho or Exquisite Corpse, it's not nearly so deranged or explicit, but for its time it's a brutal expose. A more accurate comparison could be made to Thomas Tessier's Rapture; both books are able to make their antagonist's irrationality seem rational, which is where the horror sets in. Despite a meandering chapter here and there, The Face That Must Die is an essential read for psychological horror fans. Many times Campbell hits notes that only now are we beginning to hear and understand about the minds of Horridge and his like. When Horridge finds one of Fanny's paintings is of himself, he slashes it apart with his beloved razorblade (see the Tor edition's cover, thanks to Jill Bauman); somewhere inside he knows, but can never admit, that the face that must die is only his own.

Friday, December 12, 2014

Take Another Little Piece of My Heart Now Baby

An astounding stepback image for an unremarkable '80s mainstream horror novel, Crooked Tree by Robert C. Wilson (Berkley Books, June 1981). The artist is Dario Campanile. He certainly outdid most other horror paperbacks of the era with this one! I mean, a werebear-lady feasting upon unfortunate shirtless dude...

Thursday, December 4, 2014

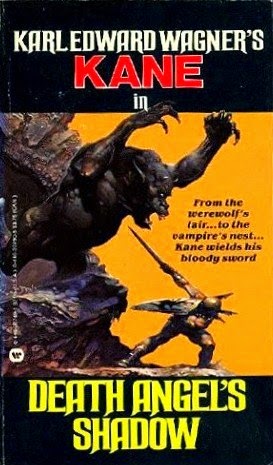

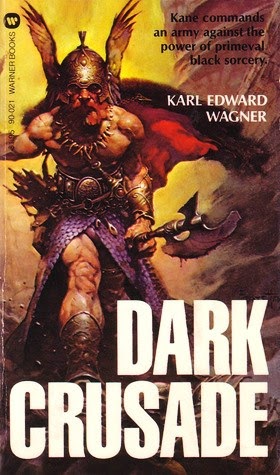

Karl Edward Wagner's Kane: The Frank Frazetta Covers

Born on this date in 1945 in Knoxville, TN, the late great Karl Edward Wagner made his bones writing countless tales of Kane, a somber swordsman from prehistory. Warner Books published these paperbacks throughout the 1970s and '80s with cover art to catch anyone's eye, thanks to the mighty Frank Franzetta's depictions of ripped musclemen in various states of dress and battle. It was a match made for the pulp ages...

I haven't read these myself--Wagner's horror fiction is more my thing--and I don't usually see these books when I'm out book-hunting. So I leave it to you guys: how much do you like Wagner's Kane books?

I haven't read these myself--Wagner's horror fiction is more my thing--and I don't usually see these books when I'm out book-hunting. So I leave it to you guys: how much do you like Wagner's Kane books?

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)