This aspect grew to the forefront by the time they published their ambitious second-to-last novel, The Bridge (Bantam Books/October1991/cover art by Lisa Falkenstern). This was adult, eyes-open horror, the guys were saying, writing about the here-and-now and not looking to horror for escape any longer: humans were no longer the sole items on the menu, for Earth itself (her self?) was on the chopping block. It was time to acknowledge that, ecologically, the planet was in dire straits.

Ecological horror stories were more a part of science fiction than horror (Skipp has often name-checked The Sheep Look Up, a 1972 dystopian novel by John Brunner, which depicts a world so polluted by human endeavors it is almost uninhabitable), but The Bridge is eco-horror in high gear. An impassioned plea for the state of our very planet that pulls no punches, it is an apotheosis of the authors' combined talents. That is, it has most of what's good about their work and some of what's bad, but it's all delivered with an earnest intensity. Dig the back-cover copy, which gives only a hint of what's lurking inside:

What results is so awful, so mind-bendingly terrifying, so rarefied and beyond man's ken that S&S have no choice but to revert to free verse poetry to describe it:

born of poison

raised in poison

claiming poison for its own

it rose

a miracle of raw creation

hot black howl of life and

death intertwined and converted to

some third new option

And so on. It's "an enormous oily serpent" that "fractures physics, disembowels logic." It is made of rotting fish and broken barrels, the sludge and slurry of the creek, and it—the Overmind—wants the bodies and souls of us hapless littering mall-dwelling gas-guzzling dullards to wreak its vengeance. Host and parasite in one. Puppets of this sentient sludge. It devours and expels, creating a misshapen, oozing, zombie horde to act as avatars of our own destruction. It is the literal embodiment of the processes that created it: the greedy, insatiable eating machine. Shoveling resources in the one end, shitting poison out the other. A fat, blind, dying carcass, smothering all as it wallowed in its own excrement.

These grotesqueries on display are beyond reproach, offered up with spunky elan, gloopy and disgusting. This roiling mass of deformed life, "toxic ground zero," is eager to ingest everything it comes into contact with, to make it one with the Overmind. Reanimated bodies, human and helpless animal alike, march—or, more accurately, drive trucks filled with nuclear waste barrels—upon the unsuspecting small town of Paradise, PA: At the center of the only Hell that mattered. The Hell that mankind had created on Earth.

Our cast of characters is large, varied, as S&S dip down and then back up the social ladder. There are the aforementioned rednecks, duplicitous businessmen, young couples in love, a pregnant woman in crisis and her New Age friend, television reporters and crew, nuclear power plant workers, hazmat crew members, and teenage punk rockers. S&S keep things on the move, never lingering too long on any one narrative thread, spiking the wobbly narrative with odes to pain like a raggedy ratcheting metal fist, a screaming bonesaw violation so far beyond ordinary pain it boiled down endorphins and tortured the steam... blowtorching her mind into into crisp hyperclarity.

The novel has faults, though, many. I read it when it came out, and the only thing I recalled before this reread was an awkward, lopsided vibe. This vibe remained: the set-up is bold and powerful, but there's no plot, only the

one-way-ticket to oblivion, a downbound train doomed to destruction,

peopled solely with folks in service to it. Hysteria and mania are at

fever pitch; some readers may tire of the terse, melodramatic

single-sentence paragraphs, or the overly earnest emotional outbursts, the endless fucking italics, or the glib, smart-alecky, even dated approach to violence, with a phrase like "Vlad the Impaler on a Funny Car Saturday" clunking in. None of the characters is the

protagonist, per se, and none really come to life except when they're

about to die, if even then. And the less said about the garden gnome orgy (pp. 260-261), the better! (Also: do not read past Chapter 60. Two very, very short pages follow, and they are from hunger and add not a drop to what you've just read.)

What we have then is a polemic aimed at the people who dump and poison without a backward glance or a twinge of remorse, who would use our environment, our home, as a dumping ground so they can fill their pockets. This ain't rocket science; S&S aren't saying anything particularly new. But that's not the point. The point is to deliver this oft-ignored message to the masses with a white-hot flaming sword, and that sword is The Bridge. It's not fully a novel; it's "a warnin' sign on the road ahead," as Neil Young once sang. But those people at fault will never read a book like this (although I wouldn't be surprised if some were Neil Young fans), and so S&S are left to include a long appendix filled with environmental tips n' tricks and the addresses of ecological organizations. It's (still, alas) up to us, and us only.

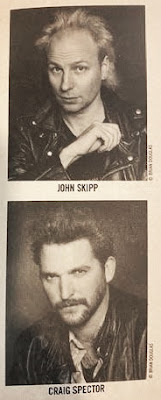

Despite those enumerated faults, I quite enjoyed my revisit to The Bridge; I was most often captivated by the book's gleeful passion, the commitment to its monstrous, unavoidable finale. And there’s no doubt eco-horror is more relevant than ever, which only added more sting to the proceedings. John Skipp and Craig Spector would only write one more novel after this, then quit for reasons I've never been able to ascertain—personal fallout? The waning of the paperback horror era? Creative differences? No matter, really. With one of the best, literally explosive, most disheartening climaxes in horror fiction of the era, The Bridge is an apex of the "new," early Nineties horror, delivered unto you without a care in the world—except saving it.

Horror was love, in this Brave New Hell: the capacity for caring, and for sharing pain.

To find oneself both in love and in Hell was more than torture, worse than madness.

It was tantamount to sin.