I can't imagine it'd surprise you to learn that I was a pretty mean dinosaur fanatic when I was a kid in the 1970s. Visits to the local

library were never complete without a stack of books on these fantastic creatures. Most of these titles were from the '50s and '60s and out of date by the time I was reading them, illustrated by timid little black-and-white pencil sketches of tail-dragging creatures, but I still recall with great fondness two from that actual decade:

A family trip to New York's American Museum of Natural History when I was in second or third grade allowed me to see the immense fossils in person. Relatives would ask me to name the various dinos, which I could rattle off pretty easily (I could also do the same with classic monster movies thanks to the infamous

Crestwood series). There was this early '70s

model kit. Lots of

plastic toys. Factor in the original

King Kong, movies like

The Land that Time Forgot, oh and especially the bottom-of-the-barrel TV movie

The Last Dinosaur, with a drunk Richard Boone battling a Tyrannosaurus and other baddies in a land at the center of the earth. Or how about the actual

Journey to the Center of the Earth? Or

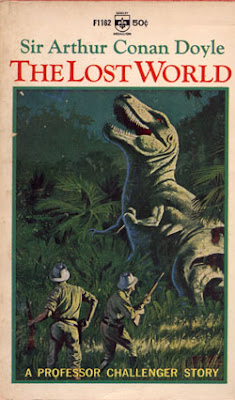

The Lost World? And who can forget Bradbury's "A Sound of Thunder"? So. Yeah. Dinosaurs.

In 1993 I went to see Spielberg's adaptation of

Jurassic Park twice the weekend it opened and was well rewarded: yep, that's the stuff I've been wanting to see since I was a kid. I even went to the mall afterwards and bought the

T. Rex, the toy I had dreamed of all my childhood (just the right size have battled an

alien or eaten a

rebel!) and proudly displayed it in all my homes for over 20 years. All of this brings me to...

Harry Adam Knight was a pseudonym used for a small handful of pulp novels by

John Brosnan (sometimes with the assist of

Leroy Kettle), a prolific Australian author who also wrote nonfiction genre studies. A fleet-footed, old-fashioned thriller with plenty of gore, in the tradition of James Herbert,

Carnosaur (Star Books, June 1984 UK/Bart Books, Feb 1989 US) is as solid a trashy paperback horror novel as one could want. Knight ticks all the boxes and doesn't muck about with the unnecessaries.

This is pulp horror done right: mean, nasty, brutish, and short. Sometimes every character is so glum and rude you kinda think, Jeez, doesn't anyone have a nice polite word to say? Everyone's all Johnny Rotten all the time. Kill the lot of 'em. Unpleasant, ungrateful, folk fodder for the dinosaur. Right...

now.

Our tale begins at 2:17 a.m. sharp when a poultry farmer is woken by his wife ("fat lazy cow" he thinks. See what I mean? What a turd) because their chickens are squawking up a ruckus. Of course, you're reading a book called

Carnosaur so you know what's about to happen when Rudie McRuderson goes out to investigate. And it does.

Then the action switches to two teens doing it in the backseat and it's more of the same, with some class-consciousness woven in as British pulp fiction seems to always do:

"She'd been flattered to have been picked up by someone who was so upper-class. Well, sort of upper class."

Daytime: David Pascal is a late 20s guy working as a "journalist" at a newspaper that's barely a newspaper in the small English town of Warchester,

"where nothing exciting ever happened." He's just dumped his wonderful girlfriend, a coworker named Jenny, because of his dreams of leaving for a job on a Fleet Street scandal rag. Who knows when that'll happen since those papers keep ignoring his applications.

So here Pascal is, still working on a paper that's practically a local business flyer and having awkward moments with Jenny in the office. But you're reading a book called

Carnosaur, so you know that Warchester is gonna offer up something soon that Fleet Street dared never dream.

Sir Darren Penward (erroneously referred to as "

Sir Penward" throughout the novel) is Warchester's wealthy eccentric, the big-game hunter with his own personal zoo on his vast estate, filled with exotic and dangerous animals—including his ravenous nympho wife, Lady Jane. But again, you're reading a book called

Carnosaur, and you know that Warchester will soon be under siege by animals much more exotic and dangerous than *yawn* tigers and panthers.

The police begin their investigation, and "Sir Penward" blames the attacks on an escaped Siberian tiger. Pascal suspects a cover-up, and along with a reluctant Jenny, begins some investigation of his own. This leads him into the clutches of Lady Jane (aka Lady Fang, and looking

"like something out of The Story of O"), well-known amongst the locals for her penchant of seducing younger men while her husband tends to his menagerie. Pascal realizes he can use her to get inside the zoo to peek around. That can't be a bad idea, can it?

Pascal has a confrontation with Penward in which all is revealed about how these extinct monsters are suddenly alive again: the painstaking genetic process that the obsessed Penward explains almost like a Bond villain, which leaves Pascal muttering,

"Incredible. Chickens into dinosaurs." Brosnan's science when it comes to dinos sounds pretty spot-on to me from what I recall of more modern paleontology books, and the distinction between

dinosaurs—terrestrial prehistoric creatures—and other ancient reptiles will prove more important than anyone but an actual scientist could imagine. But you're reading a book called

Carnosaur so that shouldn't surprise you.

I don't need to rehash the rest: Brosnan does nothing new with the plot—but that's entirely beside the point. This baby zips along with a

confident rhythm and pacing precisely because the author doesn't try to

add new twists or turns to his narrative (indeed I could have done with less "You've got to believe me, dinosaurs are in the streets, there's no time to explain!" but that is to quibble). Pulp is, in essence, comfort

reading.

Brosnan, 1947-2005

Okay, okay, I'm getting to it: the "carno" part of the title. Well, gentle reader, you won't be disappointed. The residents of Warchester—the ones still alive—woke up to a world that was vastly different to the one they'd gone to sleep in. Brosnan serves up the grue that satisfies. Behold: Tarbosaurus, a T. Rex in everything but name, wreaks delightful havoc wherever it goes; Deinonychus, with its scythe-clawed foot that it uses like a prehistoric exponent of Kung-Fu, guts hapless farmers and other locals from neck to groin; and a plesiosaur joins a boating party that none of the invitees will soon forget: After a long, stunned silence a man's voice said, with an edge of hysteria to it, "Well, you've got to say one thing for good old Dickie; he sure throws a hell of a party..."

Brosnan doesn't quite take it to ridiculous

Dinosaurs Attack! levels, but pulp fans should still have plenty to chew on. Sex, violence, nerdy dino facts:

Carnosaur has it all.

Above I mentioned Jurassic Park, and I can't leave this review without mentioning that Carnosaur features many facets that would become famous, indeed iconic, when Spielberg adapted Crichton's 1990 bestseller: chase scenes, close calls, and especially the scientific basis of resurrecting dinos are all first seen in this novel (itself adapted into a post-JP cheapie by Roger Corman). While I've never had much interest in Crichton's fiction, after reading this I feel I need to see if Crichton really did read a book called Carnosaur... or if it's simply a case of a great idea whose time had, like the dinosaurs, come again.