Pages

▼

Friday, December 30, 2016

Saturday, December 24, 2016

The Homing by Jeffrey Campbell (1980): I'm Not a Prisoner I'm a Free Man

Middling mainstream thriller with touches of Stepford Wives and Thomas Tessier's psychological ambiguities, The Homing (Ballantine Books, 1981) was written under the pseudonym Jeffrey Campbell, in actuality authors Campbell Black and Jeffrey Caine. First I found it rather entertaining, at times an ingenious puzzle, an enigma as one man tries to sort out dreams, memories, and reality through various coincidences and correspondences in the quietest little country town ever. But as the first notes of "medical thriller" began to tinkle, however, my interest began to fade, although the writing alone was engaging enough to keep me going.

Our protagonist, Manhattanite George Kenner, is trying to reconnect with his beloved daughter, once a promising psychology student but now content to live in this one-horse town of Chilton as a one-dimensional housewife married to a dopey well-meaning dork. In fact everyone in town is a boring homebody, and it chafes Kenner terribly that his daughter Katherine, with whom he'd shared private jokes and intelligent conversation as she grew up, should find herself at home amongst them. These folks are, to Kenner, committing the worst sin ever: they're fucking boring beyond belief. His acerbic wit is lost on these dullards!

Not everyone is so harmless, though: there's the cop with that crooked grin and an ironic tone (irony being in short supply in Chilton), there's the old drunk who begs for a ride out of town, or the teenage hitchhiker harassed by that same cop. And yet nothing too terribly scary or even eerie happens, and it should have. Kenner's bouts of dreamy déjà vu are mysterious, clues placed here and there but just out of reach, and his enlistment of Katherine's former professor Elaine Stromberg allows for decent romantic interplay. Cue the suspicion, the research trip, the car chase, the revelation. But nothing scary or even really eerie happens. That '70s paranoia/conspiracy theory vibe is in full effect (it's been years since I've seen it but 1966's Seconds had to be an influence) but never seems to hit hard enough, alas. The authors seem to have been phoning it in (as was the cover designer). I bet this is the kind of case Mulder and Scully would've solved before the hour was up. You've seen and read this story before. Don't bother again.

Our protagonist, Manhattanite George Kenner, is trying to reconnect with his beloved daughter, once a promising psychology student but now content to live in this one-horse town of Chilton as a one-dimensional housewife married to a dopey well-meaning dork. In fact everyone in town is a boring homebody, and it chafes Kenner terribly that his daughter Katherine, with whom he'd shared private jokes and intelligent conversation as she grew up, should find herself at home amongst them. These folks are, to Kenner, committing the worst sin ever: they're fucking boring beyond belief. His acerbic wit is lost on these dullards!

1980 Putnam hardcover

50 cents at Woolworth's. Seems about right.

1992 UK paperback

Friday, December 16, 2016

Philip K. Dick Born on This Date, 1928

Philip Kindred Dick (1928 - 1982)

Wednesday, December 14, 2016

Shirley Jackson Born on This Date, 1916

Today marks the centenary of the birth of Shirley Jackson. If you've never seen this 1969 short film adaptation of her classic 1948 short story "The Lottery," do yourself a favor and watch it! Wow I can still remember the chills it gave me when I watched it in my 9th grade English class. Read Jackson's obituary from the New York Times as well... her reputation was secure even in 1965.

Thursday, December 8, 2016

Effigies by William K. Wells (1980): Don't Shake Me Lucifer

First things first: this might be the most soused horror novel I've ever read. Everybody's always topping off their drink, or sneaking one, or suggesting they grab one together and talk, or exclaiming they need one. They're drinking while they're frantic with worry and dread over the horrible things happening to their town of Holland County and to their family members. One guy's drinking during a seance! It's like Who's Afraid of Virginia Woolf up in here. This is all okay with me. Effigies (Dell Books, Nov 1980) with its astounding Peter Caras cover of a leering visage and its lurid stepback, looks like just another creepy satanic kid paperback original of its day, with a no-name author (sorry, William K. Wells!) and lacking even the most rudimentary of relevant blurbs (what, no "Scarier than The Exorcist!", no "More shocking than The Other!", no "Makes Rosemary's Baby look like Love Story!"?). Seems like a real, well, loser. Yet I totes dug it and I did not expect to totes dig it.

The story proper: a young suburban mother, Nicole Bannister, a

children's book author and illustrator, receives a terrible shock when

she finds a package delivered to her contains a child's amputated

finger. While police chief Frank Liscomb and medical examiner Thomas

Blauvelt begin their investigation looking for a dead body, rumors start

to fly in this upscale artist community that there's witchy satanic

coven up in the woods, a spot called Job's Camp, occupied by young

itinerants who a few years before would've been called hippies. Now

they're seen—well, one of them, a crude, abusive yet charismatic

20-something named Freddie Loftus, is seen as a Charles Manson follower,

perhaps eager to start his own murderous cult...

Lots of characters, get ready: Nicole's husband Jonathan, a commercial artist working in the (dangerous) city; his colleague Henry Dixon, a bitter drunk whose tipple is Boodles gin (crime readers may note this was Travis McGee's drink as well); Dixon's wife Estelle, who feels intellectually inferior in this environments of creatives, has been digging pseudoscience as of late and has discovered the Ouija board; Father Daniel Conant, a darkly handsome yet friendly, thoughtful young priest who wishes to help Nicole deal with her shock; Maria Braithwaite, a worldly European sophisticate who eyes Americans as shallow and impulsive; Judge Oliver Marquith, expansive and greedy, eager to purchase the plot of land called Job's Camp; and more. Also: little Leslie Bannister, the girl on the cover, whose invisible playmates bode unwell for her and well everyone; babysitter Susan Dixon, who straddles the line between dutiful daughter and drug and sex experimenter up in the woods; Ken Brady, maybe her boyfriend, maybe not, he hangs around too much with that creep Freddie Loftus.

Also,

weird natural stuff is happening in town: the oppressive heat, the appearance

of giant beetles and rattlesnakes, darkening skies, your general gloom

and doom ("There seemed to be a giant pall over Holland County, like a tarpaulin covering an open grave"). To get Nicole's mind off all the unpleasantness, Jonathan throws her a birthday party and everybody's there having a high old time. One guy talks about the book he's gonna write, another declares Wertmuller can't compare to Herzog, another simply must get this recipe, and what about the "sex orgies" and LSD up in Job's Camp? Estelle and Maria and Father Conant talk about seances. Dixon gets drunk. Presents for Nicole are opened: lots of booze to ensure the party continues. And then one present in particular that no one recognizes and you can probably guess what's coming.

Meanwhile Freddie is holding his stoned gang up in the woods spellbound

with his "sermons" on the illusory constructs of good and evil. Soon

they're gonna have a special night where all boundaries are crossed

(wait till you get a load of "the pentagon"!). This night of Rites ends in a climax of sacrifice, violent sex, and whatnot. But of course! It sends Blauvelt and Liscomb into more frantic efforts to find out who Freddie Loftus really is, and if he's behind the gruesome packages sent to Nicole Bannister. Wells takes his time drawing it all together—Effigies is not quite 500 pages—and there are ugly, guilty revelations a-plenty about Freddie, about Nicole, about Father Conant to come. The title too will become clear. Disgustingly, bizarrely, satanically so.

While it's not a great horror novel by any means, Effigies provided

me with some solid hours of reading enjoyment, probably because I was

expecting so little. I never once went "Oh come on!" or "Are you kidding

me?" or rolled my eyes at a clunky descriptive phrase, an

amateur analogy, or a wooden exclamation like one too often finds in horror paperbacks—Wells, whoever he is, is a serviceable writer. The death and degradation of the '60s revolutionary spirit is part of

the novel's setup, and Wells does a nice background sketch of the era,

how the '70s came on and slowly laid waste to those ideals. I

did not get a sense of "You kids get off my lawn!" from the author's

stance; seemed fairly judgment-free to me. Everybody felt this way after

Manson, no? Maybe the author was saying something about how those lofty ideals,

once corrupted by time and age and carnal pleasures and the lure of society at large, opened up a place for evil

to slip in. But the Church also has its faultlines ripe for exploitation. What difference is there between Freddie Loftus and Father Conant?

As jaded Maria Braithwaite muses perceptively:

How

little Americans know about spiritualism, mystery, the inexplicable,

the unforeseen... Astrology, yoga, Buddhism, meditation, all become

fads, something to "do"... to show off like a new possession. Psychiatry

had been twisted, warped, torn asunder and completely reshaped into a

meaningless mass of pseudoscience... And now the American masses had

lately discovered the occult. As though it had never been there in the

first place!

Satan, Lucifer, Beelzebub were new characters in the

American drama...

What will these Americans do with their new fad?

Wednesday, December 7, 2016

The Guardian by Jeffrey Konvitz (1979): Blinded Eyes to See

It was a few years back that I tried reading The Guardian (Bantam Books, Jan 1979), well before I knew it was actually Jeffrey Konvitz's sequel to his 1974 religious horror novel The Sentinel. I gave up pretty early on, after being bored to tears by the various involved and detailed church-y goings-on. Not my scene, man. The cover should've told me all I needed to know, I mean a creepy old nun with blank orbs for eyes. Dig the '70s hair on these folks, though. Did I miss anything by skipping this one?

Friday, December 2, 2016

The Sentinel by Jeffrey Konvitz (1974): Call for the Priest

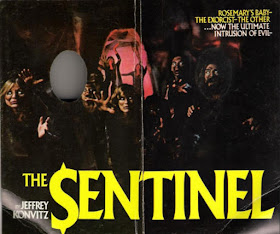

A mainstream horror bestseller in the wake of the far better novels The Exorcist, Rosemary's Baby, and The Other, 1974's The Sentinel (Ballantine paperback, January 1976) offers similar ominous occult/religious horror trappings but brings nothing new to the proceedings. I don't know what Jeffrey Konvitz did before he wrote this, his first novel, but afterwards he produced B-movies and wrote a couple more shlocky novels (one, a sequel to The Sentinel called The Guardian, was similarly unimpressive). Today it's less remembered than the also-shlocky yet star-studded 1977 movie adaptation.

Allison Parker is a fashion model returning to New York City after her father's funeral in Indiana, a place she'd fled years before due to some icky stuff going on at home. Now she's struggling with some guilt issues due to the fact that her boyfriend, big-shot lawyer Michael Farmer, was the husband of her friend Karen, who killed herself because he was having an affair... with Allison, unbeknownst to her. This soap-opera set-up is slowly parceled out to the reader, and later the "icky stuff" with her father is revealed. The Sentinel begins with Allison moving into an apartment building on the Upper West Side to get her life back in order, but the other residents she meets prevent that.

Also featuring is a grizzled city cop chomping on a cigar who's convinced that Michael actually killed Karen for her family's money and is setting Allison up the same way. Boring and predictable, neither scary nor suspenseful (unless under-pacing and ending sections with characters' faces bearing looks of terror count as suspense), The Sentinel stands not with the aforementioned classics of early '70s horror fiction but with dullards like The Searing. This is pretty much hackwork that utilizes TV cop-show tropes and the Latinate mysteries of the Catholic church liberally dosed with Dante's Inferno. Konvitz's prose is literate but not illuminating, and I can see why it was a bestseller. The climax mixes violence with otherworldly demonic forces in the guise of people from Allison's past. Not terrible, mind, but nothing really special either.

I read The Sentinel with indifference mixed with impatience over several weeks, meandering through it without really caring. This is not horror fiction as we fans know it and love it. It is solely marketing fodder branded by its betters, a hash cobbled together from commercials, soap operas, and several other pieces of extremely popular culture; it's a work of mainstream dullness that will bore and frustrate long-time readers of the horror genre thanks to its crass origins. The Sentinel's unique image is for me not even the blind priest that so unimaginatively adorns the cover. For me it's that tasteless yet effectively creepy moment of two women fondling themselves and then one another in front of Allison, a bit of unexpected shock-value that works as it transgresses social norms. It's the only moment of unsettling frisson (no pun intended) in the entire work (and yes, it's in the movie). Utterly missable and inessential despite the implied menace of the title (which really isn't that menacing when you think about it), The Sentinel will make a nonbeliever out of you.

Allison Parker is a fashion model returning to New York City after her father's funeral in Indiana, a place she'd fled years before due to some icky stuff going on at home. Now she's struggling with some guilt issues due to the fact that her boyfriend, big-shot lawyer Michael Farmer, was the husband of her friend Karen, who killed herself because he was having an affair... with Allison, unbeknownst to her. This soap-opera set-up is slowly parceled out to the reader, and later the "icky stuff" with her father is revealed. The Sentinel begins with Allison moving into an apartment building on the Upper West Side to get her life back in order, but the other residents she meets prevent that.

Back cover copy gives you the inside skinny.

Also featuring is a grizzled city cop chomping on a cigar who's convinced that Michael actually killed Karen for her family's money and is setting Allison up the same way. Boring and predictable, neither scary nor suspenseful (unless under-pacing and ending sections with characters' faces bearing looks of terror count as suspense), The Sentinel stands not with the aforementioned classics of early '70s horror fiction but with dullards like The Searing. This is pretty much hackwork that utilizes TV cop-show tropes and the Latinate mysteries of the Catholic church liberally dosed with Dante's Inferno. Konvitz's prose is literate but not illuminating, and I can see why it was a bestseller. The climax mixes violence with otherworldly demonic forces in the guise of people from Allison's past. Not terrible, mind, but nothing really special either.

Kinda cool stepback art, nothing so dramatic inside

Requisite note of better novels

Requisite note of better novels

I read The Sentinel with indifference mixed with impatience over several weeks, meandering through it without really caring. This is not horror fiction as we fans know it and love it. It is solely marketing fodder branded by its betters, a hash cobbled together from commercials, soap operas, and several other pieces of extremely popular culture; it's a work of mainstream dullness that will bore and frustrate long-time readers of the horror genre thanks to its crass origins. The Sentinel's unique image is for me not even the blind priest that so unimaginatively adorns the cover. For me it's that tasteless yet effectively creepy moment of two women fondling themselves and then one another in front of Allison, a bit of unexpected shock-value that works as it transgresses social norms. It's the only moment of unsettling frisson (no pun intended) in the entire work (and yes, it's in the movie). Utterly missable and inessential despite the implied menace of the title (which really isn't that menacing when you think about it), The Sentinel will make a nonbeliever out of you.

1976 Star Books UK paperback