A brief, stark coming-of-age tale of terror,

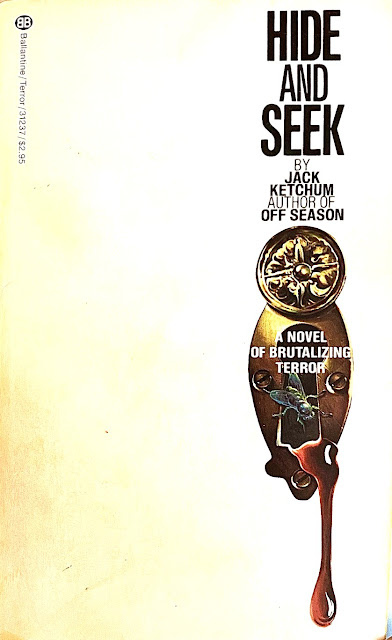

Hide and Seek was the second novel from the late

Jack Ketchum—famous pseudonym of author Dallas Mayr, who

died of cancer in 2018 at age 71. Published as a paperback original by Ballantine Books in June 1984, this slim little book reads like a James M. Cain or a Jim Thompson crime

novel, with a no-account narrator meeting an enticing woman far outside

his league (

I was way outclassed and I knew it), related

in plain prose rife with hard-boiled philosophizing, a sense of

unavoidable fate lurking behind the everyday facade.

I don't believe in omens, but I think you can know when you're in trouble. Set sometime in the Sixties, Hide and Seek is told in retrospect by Dan Thomas, a regular young guy living and working in a lumber mill in Dead River, Maine. Pretty much a dead-end town, he's in a dead-end job, but when he and another blue-collar friend are hanging out at the touristy local lake, Dan happens to meet three college "rich kids," Kimberly, Steven, and most intriguingly, Casey White. Casey, with eyes pale, pale blue that at first it was hard to see any color in them at all. Dead eyes, my brown-eyed father calls them. Depthless.

Dan is of course completely besotted with Casey, and reluctantly hangs out with Steven and Kimberly too just to be with her. Steven loves Casey but has settled for Kimberly; this is a fact known by all. They drink beer, hit the beach, skinny-dip, shoplift, pull dumb pranks. They laugh a lot but nothing's really funny. Dan meets Casey's father, who seems a broken man, and learns of a horrific tragedy in the family' life. Dan and Casey have sex in a graveyard. Just like in a classic noir novel, Casey is the femme fatale, but she's most fatal to herself; that tragedy

has caused her to be reckless, which is what frightens, and yet attracts,

our narrator. In the Middle Ages, they'd have burned her at the stake.

Ketchum builds tension well in the book's first half, with short declarative sentences, simplistic dialogue, and that sense of fatalism permeating everything—the kind of thing crime noir is known for. I appreciate his attempt at writing a horror novel that incorporates other genre elements, to infuse his stories with a grimy grindhouse slasher feel combined with tentative attempts at character detail, but to what end? I was really into the long fuse of the set-up, wondering what character flaw would trip the deadly spring I knew just had to be poised over the characters' heads. And then Ketchum reveals it, and all the goodwill built up by his careful tightening of the noose is spent. "Hide and seek. Just the way we used to play it when we were kids. But we play it in the Crouch place."

I'm going to talk freely about what happens in the second half of the story, so I guess a spoiler warning is warranted from here on.

The Crouch place Casey is talking about is Dead River's haunted house, situated on a cliff above the sea, abandoned years before by the two owners, Ben and Mary Crouch. Rumored to be imbecilic siblings, they had lived in filth with their many, many dogs. Which the couple left behind, starving and near-mad, when the police pay a visit a month after they'd been evicted for not paying their mortgage. To be honest, all this became too Richard Laymon-style for me, this scenario of teens sneaking into an empty old creepy house at midnight to play a child's game, tying up one another with nylon ropes when "found."

"How do you feel about bondage?" "I love bondage!" She finished buttoning her blouse.The novel is too "talky" and 90% horror-free for a horror novel, while the origins of its violence too hokey for a crime novel. And Ketchum is so damn solemn about everything. Lighten up, Francis! He invests too much seriousness in that trite finale, a lot of po-faced silliness that squanders all that great suspense he worked so hard to build up. A giant dog in the caverns beneath the house eating people? Monstrous Ben and Mary Crouch living down there in the earth? In a schlockier horror novel, sure. But all this time spent laying down a prosaic reality, hinting at horrors in the future that cannot be avoided, alluding to human flaws that will lead to tragedy, and then it's just some B-movie monster ripping people apart in gory, yet somehow bland detail. It's not as dumb as Laymon, you can tell Ketchum cares a lot, but it's still thin gruel for a seasoned reader.

In the Eighties, fat horror novels were the rage; books that featured lots of characters, situations, settings, plots, conflicts, and blood and scary scenes splashed throughout. Ketchum bothers with none of that. Not even 200 pages, Hide and Seek is a novella padded out to get to even that length. With this bare bones approach, he must have felt like a man without a country back then. No one really wrote this style of book, and the reason is: it doesn't work. Hide and Seek just doesn't work, not as horror, not as crime, not as coming-of-age. Why push your readers through to an end where you rip the characters apart, ostensibly for the moral of "the world is a horrible place but I think I've learned to cope"?

I never heard of Ketchum till the early 2000s, around when

The Girl Next Door was reprinted, and he published

no short stories in the Eighties, which is where I learned about new writers then. I doubt I'd have enjoyed his books anyway, as I was looking for more challenging, more imaginative vistas, writers like

Barker,

Koja,

Tessier,

Lansdale, Brite, Ligotti, etc. people stretching the boundaries of horror into weird new realms. Novels trading in giant monster dogs and slasher cannibals like this novel would've seemed to me like tired retreads of tropes I didn't care about in the first place.

Ketchum has a great reputation in the field, as a mentor and as a mensch, and his death was mourned by everyone who loves the genre. But this second novel is failed ambition, a concoction that promises terrifying delights but in the end delivers little of real interest, almost negating itself. This was the fourth book I've read by Ketchum, and while not as bad as She Wakes, Hide and Seek is a step down from, and a little derivative of, his brutal and grueling debut, 1980's Off Season. The more I thought about it the more I felt it was like a writing exercise, a very first draft, a practice session to prepare for the real thing.

Eventually Ketchum would come into his own and define his own style with The Girl Next Door—the real thing—but I'm realizing I haven't liked even his books that I consider successful. From what I've read about his later novels, many seem to be extreme scenarios of sexual violence and cruelty mixed with that fatalistic philosophy and slow build-up. Never say never, of course, but I doubt I'll be picking up one of his other books any time soon.