The house was absolutely essential,

a vital part of herself

which she recognized immediately.

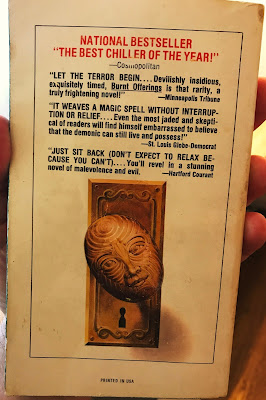

There's no getting around it, and if you've read it (or seen the movie adaptation), I'd wager the most memorable aspect of Burnt Offerings (Dell Books/Mar 1974) by Robert Marasco has to be that chauffeur driving a limousine, a suave harbinger of luxurious death. One of the "four horseman" of the early 1970s horror apocalypse—you see the other three guilty parties named on this cover—Burnt Offerings is remembered only by the die-hard horror fans, but I'm not sure how beloved it is. Marasco's novel is a staid, stately, slow-burn exploration of domestic ruin; it offers the mildest of chills with the very occasional horror set-piece. It's a modified haunted-house novel; there are no ghosts, no rattling chains, but an overarching evil power nonetheless.

Marasco (1936 - 1998)

New York City sucked in the '70s and it sucked especially in the summer back when A/C wasn't a commonplace household item. Everyone was looking to get out (a bit of a theme in vintage horror) and if you could afford it, renting a summer home was tops. Knowing she can't spend another sweltering season in their Queens apartment, Marian Rolfe finds and shows her husband Ben an ad in the paper about a countryside home to rent "for the right people," (Ben hears a dog whistle and comments racist pigs but Marian is not dissuaded). Along with their young son David in tow, they drive the couple hours upstate, out of the city, and find a home, a mansion, an estate really, set back in foresty wilds. Towering above them, ballustraded and pavillioned and mullioined and multi-storeyed, it leaves the Rolfes with jaws agape. Yet on close inspection there is much wear and tear; a mortal sin, Marian thinks.

Once inside—even more astonishing than outside—they meet the caretaker Walker and then the eccentric Allardyce siblings, sixty-ish, who chat and charm and finally do the hard sell:

"And, God, Brother!" Miss Allardyce said, "—it comes alive—tell them that, tell them what it's like in the summer."

"They wouldn't believe it... It's beyond anything you ever seen..."

But they needn't have bothered for Marian, and they even raise the price from the unbelievably low $700 for the summer to a still-unbelievable $900. And then comes the hitch, the hitch Ben has suspected: the Allardyces' "dear darling" Mother, "a woman solid as this rock of a house." She lives in an upstairs room, locked away, and will remain so even while the Rolfes live there. All you have to do, the Allardyces explain, is leave her a meal tray three times a day. They'll never even see her. No one who rented the house in previous summers—and there have been plenty!—ever saw her either. Surely there is nothing to be concerned about? Marian can sense the greatness beneath the disarray and disuse, the greatness that she can bring out and restore over their stay. And stay they do, even inviting along Ben's old yet still lively and independent Aunt Elizabeth.

Ben remains aloof from the house; an introspective, rational English teacher, he hopes to prepare for his fall courses but never seems to get around to it. For too long he cannot put his finger on the change in Marian's behavior. Marian becomes fascinated by the extensive photos of faces from Mother Allardyce's past which decorate her sitting room; Marian will sit there in a wingback chair when she delivers meals, rarely touched, to the old woman's bedroom door. That door is carved with elaborate decoration (referenced in cover art), shifting in the light, almost hypnotic. Soon Marian lies to both Ben and Aunt Elizabeth that she's actually spoken to and seen Mother, and then even begins eating her food....

Marian spends hours cleaning, polishing, dusting, rearranging, bringing the house to life, as it were. Clocks begin ticking again, the pool filter starts working, the neglected gardens spring back to lushness. A rift begin in the Rolfes' marriage ("Christ, it's a rented house, it's two months...." "Don't remind me."), and their sex life dissolves in several rather unpleasant scenes that are too tame to be truly disturbing (All Marian could think was "Let him come, for Christ's sake let him come. Now."). Things aren't good between little David and his parents: he and his father are playing around in the pool when Ben suddenly gets seriously violent, shocking poor Aunt Elizabeth who watches helplessly till David has to practically wallop his dad in the mouth with a diving mask. Afterwards, Ben feels like he's hallucinating, as an old image haunts him in reality:

There was a dream—the playback of an image really—which had been recurring, whenever he was on the verge of illness, ever since his childhood. The dream itself was symptom of illness, as valid as an ache or a queasy feeling or a fever. The details were always the same: the throbbing first, like a heartbeat, which became the sound of motor idling; then the limousine; then, behind the tinted glass, the vague figure of the chauffeur.... What's death? —he'd have to say a black limousine with its motor idling and a chauffeur waiting behind the tinted glass.

1974 French edition

And poor little Davey! The astute reader will wonder why more emphasis wasn't put on his view of the proceedings. He hurts himself climbing on some rocks the very first visit to the house, his dad tries to kill him playing in the pool, his mom's hair turns grey then white, his beloved Aunt Elizabeth is showing her fragility more and more. One night, somehow, the gas in his room is turned on and he almost dies (again!) in a harrowing bit. Marian suspects Aunt Elizabeth, who's actually a sweet character and you hate to see her so upset by Marian's hints. Things don't go well for Elizabeth after that, but that does provide one of the novel's few shock scenes.

In distressed vain Ben watches his wife drift from him, the house assuming a larger and larger psychic area in her mind and in her life: "It is the house. As crazy as it sounds, I know it's the house." "How is that possible, Ben?" "I don't know." "If it were true, darling, if I could believe what you're saying—God, don't you think we'd leave? I'd drag us all out of here so fast. But it's a house, nothing more than a house...." So yes, as the novel begins its descent into the maelstrom, as it were, and we wonder like Marian what the deal is with Mother Allardyce, we're rather drained by all the steps we've taken to get here. We will meet her, in a way, and I found the climax—"Burn it! Burn it out of me!"—and denouement to be a satisfying, eerie conclusion, open-ended but fair play to the final line.

We have to remember this was a mainstream novel aimed at general readers who gobbled up, I dunno, Jonathan Livingston Seagull, Love Story, Valley of the Dolls, The Flame and the Flower, you know the names, and not just those other apocalyptic horsemen. Modern readers may be frustrated with the holding-pattern narrative: too many implied threats, too many indecisive arguments, and experienced horror fans already know what's going on, what's been going on, but Marasco is not a genre writer, and there's nothing in Burnt Offerings that would make you think he'd read any horror.

Personally I don't rate or enjoy Burnt Offerings as much as those three other works of the same era, nor as highly as similar titles like The House Next Door, The Shining, or The Elementals. When I first read it back in 1994, I was deeply unimpressed. Then again I was reading some powerhouse stuff at the time: Haunting of Hill House, Our Lady of Darkness, Grimscribe, as I recall. This reread, I found it to be more agreeable, but it is not gonna scare the bejabbers out of you, nor is it unputdownable or scarifyingly chilling—all those quoted blurbs are so much PR hot air—but it is an integral work of the pre-King horror-bestseller era. Perhaps it is subtler and more sophisticated than I'm giving it credit for and my brain muscles are just atrophied from reading too much, well, horror fiction. Burnt Offerings is a work that can reward the patient, thorough reader, and remains in print today. You could spend your summer worse places.

Valancourt Books, 2015