It was 20 years ago this month that the Dell/Abyss line of contemporary horror fiction began publication. Yes, 20 years! Ah, I remember it well. This imprint from Dell Publishing was spearheaded by Bantam Doubleday editor Jeanne Cavelos in an attempt to give the paperback horror genre a boost of originality and conviction - and, of course, a boost in sales - as it had long been plagued by tired cliches and half-hearted imitations of better books and writers. The appropriately-named Abyss was intent on publishing works that plumbed dark depths of psychology and the supernatural not for cheap, exploitative, escapists thrills but for more disturbing and revelatory chills. This kind of horror was interiorized, found not in a Gothic mansion or small town overrun by vampires but in the blasted landscape of the human mind.

It was 20 years ago this month that the Dell/Abyss line of contemporary horror fiction began publication. Yes, 20 years! Ah, I remember it well. This imprint from Dell Publishing was spearheaded by Bantam Doubleday editor Jeanne Cavelos in an attempt to give the paperback horror genre a boost of originality and conviction - and, of course, a boost in sales - as it had long been plagued by tired cliches and half-hearted imitations of better books and writers. The appropriately-named Abyss was intent on publishing works that plumbed dark depths of psychology and the supernatural not for cheap, exploitative, escapists thrills but for more disturbing and revelatory chills. This kind of horror was interiorized, found not in a Gothic mansion or small town overrun by vampires but in the blasted landscape of the human mind.

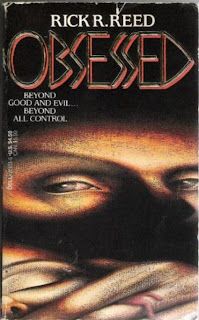

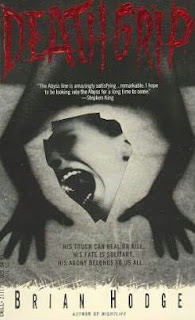

The Abyss paperback originals used striking cover design - haunting, creepy, anguished faces and tormented bodies, albeit perhaps sometimes a tad clumsy - to separate themselves from the anonymous bloody skulls, graveyards, and evil babies then on horror covers. The icon on the spine of its books was a mark of distinction; indeed, Abyss even had a mission statement:

Launched in February 1991 with Kathe Koja's stunningly bleak and unsettling The Cipher, Abyss published one title a month, ending up with more than 40 titles overall. Most of the authors were first-time novelists, or at least writers with only a few books under their belts, but in the case of MetaHorror (July 1992), an anthology edited by ever-present '80s author Dennis Etchison, the line also featured well-known horror masters. Women writers were plentiful - the most successful was easily Poppy Z. Brite, but also Tanith Lee, Nancy Holder, Kristine Kathryn Rusch, Melanie Tem - and guys like Brian Hodge and Rick R. Reed really got started here. What they all had in common was a desire to do something new with horror fiction. But, for various industry reasons, Abyss folded later in the '90s and my love of current horror pretty much went with it.

Launched in February 1991 with Kathe Koja's stunningly bleak and unsettling The Cipher, Abyss published one title a month, ending up with more than 40 titles overall. Most of the authors were first-time novelists, or at least writers with only a few books under their belts, but in the case of MetaHorror (July 1992), an anthology edited by ever-present '80s author Dennis Etchison, the line also featured well-known horror masters. Women writers were plentiful - the most successful was easily Poppy Z. Brite, but also Tanith Lee, Nancy Holder, Kristine Kathryn Rusch, Melanie Tem - and guys like Brian Hodge and Rick R. Reed really got started here. What they all had in common was a desire to do something new with horror fiction. But, for various industry reasons, Abyss folded later in the '90s and my love of current horror pretty much went with it.

I'm not exactly sure how I first heard of the Abyss books; it may have been a Linda Marotta review in Fangoria, or maybe a review from the Overlook Connection catalog. Reading Koja, Brite, Hodge, and others back then was a revelation, one of the most exciting times I've had as a horror fiction reader. I doubt all the novels and two short story collections were as "cutting edge" as promised, but I always loved the ambition and the effort. Some writers launched new careers, others weren't heard from again. I've read a handful over the years but nothing could compare to Koja's first two novels, or Hodge's Nightlife (March 1991). Still, the Dell/Abyss line was a great moment in paperback horror, and deserves to be remembered today. Most titles are readily available used, cheap (ah, except The Cipher, which has now gone to collectors' prices!) on Amazon, eBay, ABE, and the like. The following are a random sample.

Facade, Kristine Kathryn Rusch (February 1993)

Facade, Kristine Kathryn Rusch (February 1993)

Lost Futures, Lisa Tuttle (May 1992)

Lost Futures, Lisa Tuttle (May 1992)

Post Mortem, ed. by Paul Olson and David Silva (January 1992)

Post Mortem, ed. by Paul Olson and David Silva (January 1992)

X, Y, Michael Blumlein (November 1993)

X, Y, Michael Blumlein (November 1993)

Anthony Shriek, Jessica Amanda Salmonson (September 1992)

Anthony Shriek, Jessica Amanda Salmonson (September 1992)

Shadow Twin, Dale Hoover (December 1991)

Shadow Twin, Dale Hoover (December 1991)

The Wilding, Melanie Tem (November 1992)

The Wilding, Melanie Tem (November 1992)

Tunnelvision, R. Patrick Gates (November 1991)

Tunnelvision, R. Patrick Gates (November 1991)

Making Love, Melanie Tem & Nancy Holder (August 1993)

Making Love, Melanie Tem & Nancy Holder (August 1993)

Dusk, Ron Dee (April 1991)

Dusk, Ron Dee (April 1991)

Dead in the Water, Nancy Holder (June 1994)

Dead in the Water, Nancy Holder (June 1994)

Bad Brains, Kathe Koja (April 1992)

Bad Brains, Kathe Koja (April 1992)

You can read here a long, detailed, scholarly look at the nuts-and-bolts of the Dell/Abyss line, "The Decline of the Literary Horror Market in the 1990s and Dell's Abyss Series": What makes the Abyss line a cultural phenomenon worthwhile of study is its self-conscious positioning within the declining horror market. Its marketing strategies, text selection, and construction of a commodity identity speak volumes on the horror market and its transformation at the time.

This image thanks to Trashotron

This image thanks to Trashotron