Originally published in paperback by Sphere Books in the UK in July 1985,

Books of Blood Vol. VI completed

Clive Barker's era-defining collection of short stories. Written in the evenings by hand after working days in London's underground theater circuit, these 30 stories in total were '80s horror fiction's watershed and its high-water mark. This final volume can stand with the rest; before turning to his unique brand of epic dark fantasy novels, Barker ended his

Books on a high and inspired note of horror, a talent fully matured (these stories weren't published in the United States till 1988, when they appeared in hardcover under the title

Cabal, the name of Barker's then-latest work, which they accompanied).

Barker's own handwritten ms. for the Books of Blood

Readers and publishers loved to compare Barker to King and -

gack! - Koontz back in the day, and that has always seemed an ill-fitting comparison to me. While Barker may, at least in these early writings, have lacked the human warmth and bestseller plotting mechanics that gave K&K their huge middle-America audience, Barker is worlds ahead of them when it comes to style and imagination; he is also literary in a way those guys aren't. Barker easily employs irony and wit to his horrors; an erotic and perverse sexuality is threaded throughout; the metaphysics, if you will, of his stories aren't borne out of old monster movies or tawdry thriller novels but from ancient mythology, classic European art and philosophy, and obscure religious history (bet you didn't know a

cenobite was a real thing!). Not content to simply

scare us, Barker's world is one in which characters confront death, confront monsters, and learn to accept that sometimes banishing "the other" will result only in a world less worth living in, one that's been sanitized and banalized till it's fit for consumption only by toothless children.

The first story is "The Life of Death," and one might think it a trite title but the tale itself lives up to that literalization. It also is a perfect example of how facing fears enables us to see the world afresh... even as we see it for the last time.The world of Elaine Rider, a 34-year-old woman who's just had a hysterectomy and almost died twice during the surgery, has now become wintry and dull; she cries all the time and feels utterly bereft. That is until she happens upon the excavation of a 17th century church, All Saints, and meets near the underground crypts an interesting man, Kavanaugh, who piques her curiosity about whatever lies within those walls. He

had legitimised her appetite with his flagrant enthusiasm for things funereal. Now, with the taboo shed, she wanted to go back to All Saints and look Death in its face. But it won't be as simple as all that, of course, not with Barker at the helm.

The jungles of South America, and the greedy foreign interlopers looking to exploits its riches, feature in "How Spoilers Bleed." Confrontation between those deceitful men and a tribal chieftan ends in death; curse is imposed; watch the bodies felled. But it is the precision of the curse, its nightmare delicacy, that unsettles:

In the antiseptic cocoon of his room Stumpf felt the first blast of unclean air from the outside world. It was no more than a light breeze... but it bore upon its back the debris of the world. Soot and seeds, flakes of skin itched off a thousand scalps, fluff and sand and twists of hair; the bright dust from a moth's wing... each a tiny, whirling speck quite harmless to most living organisms. But this cloud was lethal to Stumpf; in seconds his body became a field of tiny, seeping wounds.

Oh, that's not going to end well at all.

One of Barker's strengths, I think, is that he never dipped into that seemingly bottomless well known as the Cthulhu mythos. He wasn't above mixing genres, however, in several of his stories he went to other wells - here, hardboiled crime fiction in "The Last Illusion," and Cold War spy fiction in "Twilight at the Towers." The latter has spies, no strangers to shedding and changing skins, subjugating personalities that, upon discovery, could get them killed. Surely there is power in that half-forgotten personality, power still within reach? Ballard is sent on the trail of potential KGB defector Mironenko, but petty bureaucracy and petty, angry men seem always in the way. Mironenko, Ballard will find, has more in common with him that he thought, and the defector will show that beneath the skin - ever-changing - the two are brothers. Becoming a spy, Ballard lost a part of himself, but

the thing he was becoming would not be named; nor boxed; nor buried. Never again.

1992 French paperback

Harry D'Amour is one of Barker's few characters that

spans stories and novels and movies, and he appears in "The Last Illusion," a New York City detective in the classic world-weary Bogart tradition. But D'Amour is

otherworldly-weary, dealing as he does - for a price, of course - with real magic and real demons. The Castrato is one of those:

It did not carry the light with it as it came: it was the light. or rather, some holocaust blazed in its bowels, the glare of which escaped through the creature's body by whatever route it could. It had once been human; a mountain of a man with the belly and the breasts of a neolithic Venus. But the fire in its body had twisted it out of true, breaking out through its palms and its navel, burning its mouth and nostrils into one ragged hole. It had, as its name implied, been unsexed; from that hole too, light spilled.

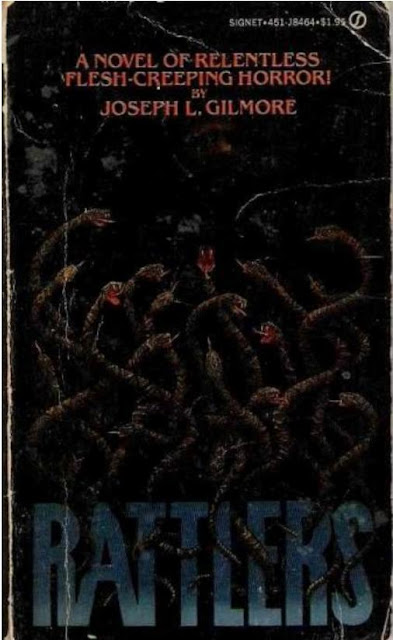

Sept 1989 Pocket Books paperback - probably the worst of Barker's book covers

A short-short tale ends

Volume VI, one that didn't appear in

Cabal; it is "The Book of Blood (a postscript): On Jerusalem Street," and it brings the entire story arc back to the beginning, the very first tale told in

Volume I, quite nicely. I hadn't read this volume in well over 20 years; in fact, I'd never finished "The Last Illusion," and the only one I recalled anything about was "How Spoilers Bleed," and that because of its perfectly abrupt ending. Again, Barker in no way let me down as I found these final pieces a fitting end to perhaps '80s horror fiction's greatest artistic achievement.

Volume VI might not be my favorite - to be fair my favorite tales are spread across all the

Books - but it is, as virtually all of Barker's '80s output, essential horror reading.

The dead have highways.

Only the living are lost.

.jpg)